![]()

PART ONE

The Context of Spiritual Kinship

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The sources

One of the difficulties of attempting to investigate any social phenomenon in the past is the need to negotiate between the particular and the general. In this process, the connection between intensive local research and the crucial national context often becomes obscured. This problem is acute in the study of godparenthood in early modern England, where the sources are diverse and diffuse, and thus need to be placed in both national and local perspectives. This study also depends heavily on a type of source that has been previously overlooked by a number of historians interested in this field of enquiry. The very existence of this material has considerable implications for an understanding of early modern spiritual kinship, implications which need to be explored in some detail.

The national context

Liturgical writings, and the dialogue that surrounded them, are especially important in the study of baptism and spiritual kinship. Liturgy can be seen as a national index of intended religious practice. Before 1549, the English liturgy was essentially regional, although the use of Sarum was predominant in the southern province and that of York in the North. Perhaps the most important mechanism for the dissemination of unified religious ideas and practice was the succession of prayer books produced by the church authorities in 1549, 1552, 1559 and 1662. To these, we can add The Directory of Public Worship of 1644, which proved a high watermark in the struggle for further reformation.

In a similar way, laws, both ecclesiastical and civil, constitute a national framework that can be used to examine some aspects of baptism and godparenthood. The changing statue law of the 1530s, added to the canons and constitutions of the church over the following century, provide an important element in understanding the baptismal ceremony and the role of godparents. Before 1534, the kinship system in England was governed under canon law, but the confusion created by the break with Rome was not resolved until Archbishop Parker published the Tables of Kindred and Affinity in 1560. They were revised three years later; ratified by the canons of 1603 and published, at the back of the prayer book, from 1681.1 However, these tables disregarded spiritual kinship, which, as we have already seen, had effectively been abolished as a bar to marriage by the four marriage acts of the reign of Henry VIII. These acts did so implicitly, rather than explicitly, reducing the scale of the kinship barriers to marriage, by reference to the book of Leviticus as the ultimate source of authority.2 There were also a series of challenges and some changes to the role of godparents in the baptismal ceremony itself, enshrined not only in the liturgy, but in ecclesiastical legislation, the most significant of which were the canons of 1603.3

Personal and biographical materials, although they might be properly considered as local sources, with their writers firmly locked into particular social networks, because of their relative infrequency in this period, can only be examined at a national level, where comparisons between them can be productively made. Such sources, by definition products of the literate and leisured orders, carry an inherent social bias. This bias was, however, not evenly distributed across the period. From the first half of the sixteenth century, there is perhaps only one diary in the modern sense of the term, that of Edward VI, but from the second half of the century there are 11. For the early part of the seventeenth century, 20 such journals are available, rising to 37 in the second half of the century and 47 in the first half of the eighteenth.4 This escalation in source material is highly significant, although not always explicitly noted by historians. Thus, in reference to spiritual kinship, it is hardly surprising that much less of the debate between traditionalists and evangelicals in the early sixteenth century is evident, than of that between conservatives and Puritans in the seventeenth century. An expansion in this period from the diary of a king, to include that of a seventeenth-century artisan like Nehemiah Wallington, is also highly suggestive of a literary phenomenon which was deepening its social range.5 In addition, the content of such diaries tends to have become more informal and personally revealing as time went on. They were also often as much spiritual as social records, and were not designed to allow the investigation of the mentalité of early modern individuals. The situation is not, however, as bleak as a study of diaries in isolation suggests, other sources, in particular letters, have a longer history, surviving in large numbers from the fifteenth century.

The local context

The administration of law and religion in early modern England functioned on many levels, from the central civil and ecclesiastical courts, through the provincial and county courts, down to the village, or more properly the civil and ecclesiastical parishes and the manor. For the purposes of this study, the most important bodies of evidence are those produced by institutions that functioned on a regional and local basis. At this level, the records of the minor church and criminal courts not only permit an examination of a statistically meaningful and manageable body of material, but they also allow historical investigation on an intermediate level, between the specific and the general. Two bodies of material are particularly important for this study: first, the records produced by those courts regulating personal and religious conformity and, second, the records of the church in its administration of probate.

The records of the church courts, in particular those of consistory and archdeaconry jurisdictions, have proved fruitful ground for social and religious historians over the last three decades. To these, we may add the more neglected episcopal visitations, which contain similar, if less detailed information. However, because matters concerning spiritual kinship appear in these records only very occasionally and often purely incidentally, these do not present a useful source for statistical analysis, but instead add a qualitative dimension to our understanding of the institution. They have thus, inevitably, been used across the country, and thus regional as well as religious differences must be borne in mind in this examination.

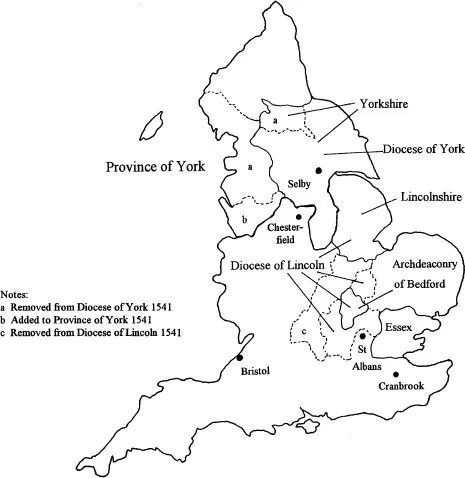

Similarly, the records of probate which are used systematically in this study, as can be seen in Figure 1.1, have been drawn from a number of areas, including the towns of Bristol in Gloucestershire, Chesterfield in Derbyshire, Cranbrook in Kent, Selby in Yorkshire and St Albans in Hertfordshire, the counties of Bedfordshire, Essex, and Lincolnshire but, most importantly, the Province of York. Altogether with the wills of the case study parishes (but excluding many groups of wills that were used anecdotally, rather than systematically) these sources provide a total of just over 10000 wills, making this one of the largest surveys of testamentary behaviour yet undertaken.

Of these wills, 5969 come from the Province of York. This area, under the authority of the various courts of the archbishops of York, consisted of the counties of Yorkshire, Lancashire, Westmorland, Cumberland, Northumberland, Durham, the Isle of Man, Nottinghamshire and (after 1541) Cheshire.6 The archbishop possessed a superior jurisdiction in matters of probate over this entire area, which was directed through a prerogative court. This functioned in a similar way to the prerogative court for Canterbury, dealing with the estates of those who had held land to the value of £5 under the jurisdiction of more than one lower court. Within this area, a more direct jurisdiction was held over the smaller Archdiocese of York, which consisted of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and the Archdeaconry of Richmond (which covered part of the North and West Ridings, northern Lancashire and part of Westmorland and Cumberland).7 In 1541, this vast archdeaconry was separated from the diocese to form the northern part of the Diocese of Chester.8 This expanded zone remained within the province and the archbishops retained their direct jurisdiction over the still considerable remaining Diocese of York.

1.1 Areas from which samples of wills were drawn for this study

Source: A. J. Camp, Wills and their Whereabouts (London, 1963); J. S. W. Gibson, Wills and Where to Find Them (Salisbury, 1974).

Wills from within this zone were largely proved in the Exchequer Court at York.9 However, within this region there were over 80 courts with rival probate jurisdictions, including a handful of manorial courts, peculiar courts of the Dean and Chapter, a Chancery Court of the Archbishop and several minor jurisdictions, including the Corporation Court at Hull. All this made the probate jurisdiction in this area among the most complex in the country.10 Except for the period 1636–52, very few original wills survive from these courts.11 Instead, the historian must largely rely on the copies of wills made into probate registers. This not only ensured the survival of most wills in an easily accessible form, but it also somewhat simplifies this complex picture, as the records of the Exchequer were copied into the same registers as those of the Prerogative Court, as were most wills from peculiar courts for the diocese at least before 1660.

An understanding of the changing and overlapping jurisdictions of these courts is crucial to their employment as an historical source. Since extensive use is made of these wills in Part Three of this book, it is important to note that they were drawn together through different legal processes. It also means that the geographical area covered by these wills covers most of the north of England, but only in the upper categories of society, whose wills came through the Prerogative Court. This may be seen as introducing a social bias into the will samples used; however, it is important to note that any sample of early modern wills contains such a bias, since they were not universally made or equally distributed throughout early modern society.12

It is equally important to note that the existence of a Chancery Court of the Archbishop, which proved wills from beneficed clergy with estates worth less than £5, meant that these clergy do not appear in the samples of wills used. More wealthy clerics had their wills proved in the Prerogative Court, and thus clergy in this sample are not representative of this profession as a whole, but of its upper strata. Because the wealth of clergy tended to increase in the period, and the threshold remained constant, this group was declining in size. However, since the volume of wills proved in the Chancery Court was small this problem is not particularly significant.

In addition, it is necessary to understand the massive ...