![]()

1 ELT at tertiary institutions in China1

A developmental perspective

Xiaoxiang Li

A briefing of ELT situations in China

Teaching English as a Foreign Language at tertiary institutions plays a special role with some unique features in China which may be considered from the following perspectives: English is taught in most colleges and universities as a compulsory course for a population of over 35.59 million students working towards junior college diplomas, undergraduate degrees and graduate degrees, the English-related course credits (usually 12 to 16 credits covering English for General Purposes [EGP], English for Academic Purposes [EAP], English for Academic & Special Purposes [EASP], English for Specific Purposes [ESP], Bilingual, Content-Based Syllabus [CBS], English-Only courses) amount to 7%–9% of the total credits (usually 140 to 160 credits) required for graduation with first degrees; English courses must now comply to a national syllabus (currently called the Curriculum Requirements and coming out soon in a new version called the Guidelines For College English Teaching2) and for most colleges and universities, English courses are delivered with sets of recommended English textbooks and in some colleges and universities with sets of teaching or autonomous learning software. Of all courses delivered at tertiary institutions today, English is the only course that has a nationally recognized summative assessment test called the College English Test (CET), Band 4 and Band 6 (CET 4 and CET 6), which attracted over 18 million test takers in 2015 alone. The College English Test is a high-stakes test, accompanied by a certificate that is often a basic requirement not only for graduation but also in many cases for job seeking. Thus the impact of English teaching goes far beyond that of any other single course delivered in tertiary institutions in China, for the outcomes of English courses in many universities and colleges affect to some extent, the possibilities of obtaining a degree and even affect the feasibility of getting a good job at graduation and so has become an issue with academic, social and economic consequences. Therefore, the quality of English teaching in tertiary institutions has captured the attention or concern not only of students and teachers of English but also of families, businesses, educational administration, and the government.

Developments of college English syllabus and curriculum requirements

The last two decades have witnessed a continuing process of revising course syllabus, reforming ELT models, initializing the reform of assessment instruments and enhancing English faculty development in order to improve the quality of College English teaching in China. The first version of the national syllabus appeared in 1980 after the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). It highlighted the following four features: orientation of reading skills development, content areas focusing on scientific and engineering contexts, a solid foundation of English including the knowledge of grammar and vocabulary capacity and practice of English language skills for professional development (Dai & Hu, 2009). This syllabus was reflective of the social and economic situation at that time when China had just opened her doors to the outside world, and followed a basic principle for English teaching with Chinese characteristics: laying a solid foundation for future use. Therefore, it can be regarded as a skills and lexical syllabus with some grammatical components. However, it was not in use very long before being replaced by the two national syllabi for College English teaching officially issued by the State Education Commission (currently called Ministry of Education) in 1985 and 1986, respectively. One was for science and engineering universities and colleges, and the other for comprehensive universities and social sciences and humanities colleges.

The basic structure of the two syllabi seems quite up to the academic standard with six parts: subjects, objectives, teaching requirements, teaching arrangements, assessment and advice on issues of common concern. One of the prominent features of these syllabi is that English language skills, especially reading skills and vocabulary development, were still given top priority, echoing the main feature of its precedent. Other features include the categorization of language skills into three levels in terms of their importance in the syllabus: reading skills, listening and translation skills, and speaking and writing skills. As specified, developing students’ reading skills was listed as the main objective of the English course as it was assumed that reading skills would be most likely to benefit students after graduation in their professional development reflecting a typically instrumental and practical viewpoint, while listening and translation skills were listed at a secondary level, and speaking and writing skills at a supplementary level, for instance, the requirement for speaking skills is to answer questions orally in relation to the texts under discussion in class.

The notions and functions of English for communication were added as a result of the communicative approach popular during the 1980s. The difference between the vocabulary lists in the two syllabi lay in the selection of vocabularies in relation to the subject matter in two kinds of targeted institutions; translation skills were emphasized in the syllabus for science and engineering students but not so much in the other syllabus. Compared with the early syllabus issued in 1980, there were some breakthroughs in syllabus development. One was to place listening and speaking skills as minor objectives of the course and the other to stage formally a national unified summative assessment at the completion of a two-year-long instruction in college English.

Both of the syllabi came into use for just 14 years before being confronted with yet another call for revision to highlight productive skills for communication. As a result, in 1999, the two syllabi merged into one which reshuffled the five language skills into two categories with reading skills as a primary objective and the rest as secondary objectives. Meanwhile, the new syllabus emphasized the notion of a common core of general English for all universities and colleges and promoted the concept of graded teaching according to local teaching and learning contexts. This syllabus divided the course objectives into three levels: the basic requirements, the intermediate requirements, and the advanced requirements, which granted colleges and universities the liberty to choose any of the three levels as their own teaching objectives for all of their students or for different groups of their students within a college or university according to their local resources and situations. However, the new syllabus was regarded soon after its appearance as still lagging behind the times and failing to meet the demands of social and economic development for qualified graduates with relatively good English proficiency and cross-cultural communication skills. In 2002, a new initiative was proposed to revise the syllabus after a very extensive nationwide survey of ELT needs analysis, and an expert team was summoned for the work of revision. The revised version for trial use came out in 2004, and the final version was not officially issued until 2007 after considerable consultation and feedbacks were collected for its finalization. There were some unique features in this new version. The first and most distinctive was the replacement of the word ‘syllabus’ with ‘curriculum requirements’ in the document which adopted a new title “The College English Curriculum Requirements” (Requirements, hereafter). Behind it lay the rationale that China is a huge country and the unbalanced development of different regions led to the unbalanced development of individual universities and colleges. Therefore, the Requirements only stipulated general requirements for College English teaching and each college or university was advised to work out its own syllabus with reference to its own local teaching and learning contexts. Such a document would hopefully in turn, encourage school-based English curriculum development so as to offer students more learning opportunities for their specific purposes or experience in their extra-curriculum activities. This recognition of the geographic and economic realities of contemporary China was analogous to a school-based approach to quality teaching in secondary education (Li, 2007). Such a change aimed at further enhancement of school-based autonomy in terms of setting up specific teaching objectives and promotion of graded teaching strategies among tertiary institutions exhibiting enormous differences in standards and approach. Second, the document redefined teaching objectives from three perspectives – communicative competence, autonomous learning, and cross-cultural awareness – as follows:

to develop students’ abilities to use English in a well-rounded way, especially in listening and speaking, so that in their future studies and careers as well as social interactions they will be able to communicate effectively, and at the same time enhance their ability to study independently and improve their general cultural awareness so as to meet the needs of China’s social development and international exchanges.

(CIP, 2007)

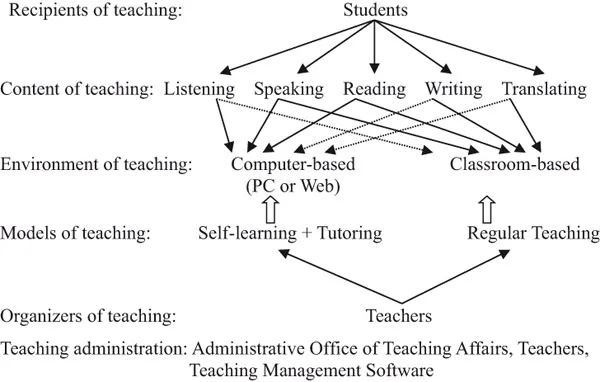

Third, along the lines of the aforementioned, the hierarchy of language skills was reshuffled once again, and in this document lay a strong advocacy for oracy to be central to the learning and teaching process with an unprecedented focus on listening and speaking practice in teaching and learning, and it enhanced students’ cross-cultural awareness and abilities. Fourth there was a strong promotion of the application of information and communication technology as a potentially effective model for teaching and learning which might help universities and colleges respond effectively to the shortage of qualified English teachers and teaching resources (Wang & Chen, 2006). A clearly depicted computer-assisted, web-based and classroom-based teaching model with a basic guideline for practice was promoted. As seen in Figure 1.1, “teaching activities such as listening, speaking, reading, writing and translation can be conducted via either the computer or the classroom teaching. The solid arrow indicates the main form of a certain environment of teaching, while the dotted arrow the supplementary form of a certain environment of teaching”

Figure 1.1 Computer-and-classroom based college English teaching model

According to the model, there was a task allotment for both human instructors and computers, an integration of different teaching resources and an administrative reinforcement to ensure optimal outcomes of the course. Also proposed in the Requirements was an example of a process of computer-based English learning activities which stated:

Freshmen take a computer-based placement test upon entering college to measure their respective starting levels, such as Grade 1, Grade 2 or Grade 3. After the teachers determine the grade and establish account for all students based on their test results via the management system, students can start to study courses according to teachers’ arrangement. After learning continues for a certain period of time (set by the universities and colleges), students can take the Web-based unit test designed by the teachers. Then students automatically enter the next unit if they pass the test. If they fail, students then return to the current unit and repeat the whole learning process. When they are ready (after studying a few units), students should receive tutoring. After individualized tutoring, teachers can check students’ online learning by means of either oral or written tests, and then decide whether the students can pass. If they pass, they can go on to the next stage; if they fail, they should be required by teachers to go back to a certain unit and re-study it until they pass.

(CIP, 2007, p. 44)

Actually, in practice there were some variations which were tailored to fit the reality of different universities and colleges. In Southeast University, for example, students could choose English teachers and tutors after being assigned to different grades according to the results of their placement test, and they could do it again at the beginning of each semester.

Looking back over the years’ efforts in syllabus development, it is easy to see a continuing underlying motive to bring about some new philosophical concepts along with full considerations of the local realities. So far as the Requirements are concerned, they are by no means perfect but they are already a step in the right direction. It would be fair to draw a conclusion that the pace of revisions and substantial changes in principles and content areas in the syllabus development demonstrates a swift and positive response of the ELT community to the demands raised by social and economic development.

Strategies for implementation of the curriculum requirements

It was understandable that the Requirements demanded a clearly aligned teaching model which would ideally result in learning outcomes that could be recognized by internal and external evaluation systems. It was also expected that the Requirements could facilitate the creation of an autonomous environment that allowed individual universities and colleges to determine their own resource allocation and missions, to develop their own school-based syllabi with reference to the Requirements and to innovate their own curricula coupled with a workable teaching model for their respective objectives. It seemed that the Requirements with a top-down nature called for bottom-up initiatives for a timely and effective response, which in fact turned out to be very tough, demanding and somewhat conflicting tasks for ELT practitioners and administrators, and at the same time left ample room for both reformers and conservatives to adapt themselves to the Requirements in times of change.

However, it was clear that t...