eBook - ePub

Standing on the Shoulders of Darwin and Mendel

Early Views of Inheritance

David J. Galton

This is a test

Share book

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Standing on the Shoulders of Darwin and Mendel

Early Views of Inheritance

David J. Galton

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Standing on the Shoulders of Darwin and Mendel: Early Views of Inheritance explores early theories about the mechanisms of inheritance. Beginning with Charles Darwin's now rejected Gemmule hypothesis, the book documents the reception of Gregor Mendel's work on peas and follows the work of early 20th century scholars. The research of Francis Galton, a cousin of Darwin, and the friction it caused between these two are a part of longer story of the development of genetics and an understanding of how offspring inherit the characteristics of their parents. Bateson, Garrod, de Vries, Tschermak and others are all characters in a scientific story of discovery, acrimony, cooperation and revelation.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Standing on the Shoulders of Darwin and Mendel an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Standing on the Shoulders of Darwin and Mendel by David J. Galton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Evolution. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter one

Seeds of hero worship

A Statue of a Hero with legs of iron, its feet part iron and part clay.

Daniel 2.34

It probably began as one of those intense emotional crushes that young boys sometimes feel for older cousins. It gradually developed into one of the worst cases of hero worship perhaps ever recorded. Even at the age of 64 years the hero worship burned as strongly, and Frank publicly confessed in a lecture that: I rarely approached his general presence without an almost overwhelming sense of devotion and reverence, valuing his encouragement and approbation more perhaps than the whole world besides. This is the simple outline of my scientific history.

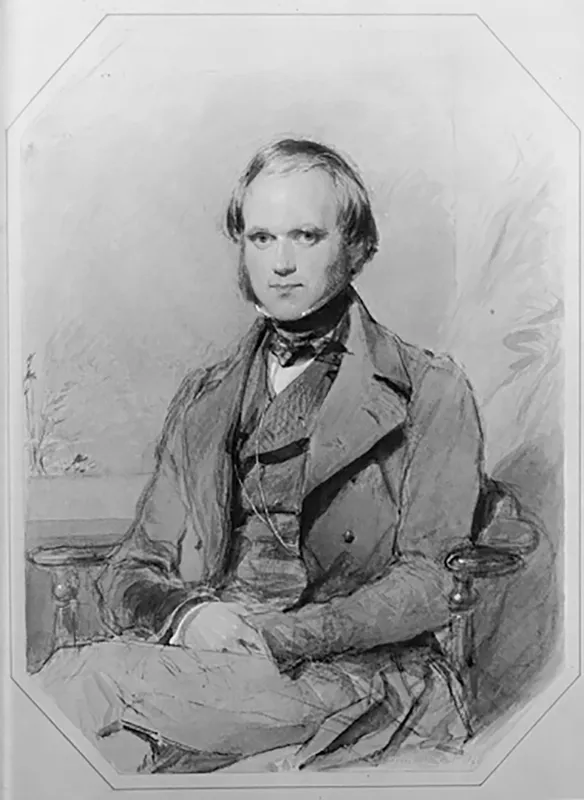

Frank first met Charles at an impressionable age—Frank was just 6 years old, Charles, a medical student, was 19 when he came to visit the Galton family in Sparkbrook on the outskirts of Birmingham in 1828 (Figure 1.1). The Galton’s estate owed their wealth to Frank’s grandfather on his father’s side who was something of an anomaly. He had amassed a large fortune in the manufacture and sale of arms for the Napoleonic wars of 1808–1814. He also professed to be a good Quaker promoting pacifism and the renunciation of war; he argued that what his customers did with his products was their affair and that guns might even deter conflict. This did not satisfy his colleagues and he was expelled from the Birmingham Society of Friends for fabricating instruments for the destruction of mankind. Frank’s father, Samuel Tertius Galton, inherited a large part of his grandfather’s wealth and had added to it by fulfilling the duties of a competent banker in Birmingham. He had founded a successful bank in Steelhouse Lane that enlarged their fortunes still further. He was happy in marriage to a joyful and unconventional young woman, Violetta Darwin, who was the daughter of Dr. Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802), a talented physician and a published poet of some distinction. Erasmus Darwin was the father of a well-to-do family doctor in Shrewsbury, Dr. Robert Darwin, whose son Charles was the cousin under whose spell Frank fell.

By 1827, the Galtons were living at the Larches, a fine country residence in the Sparkbrook district of suburban Birmingham. The name Larches came from two exceptionally tall larches that guarded either side of their driveway, and Francis (who was always called Frank by his family and close friends) was attracted ever after to this type of tree. The house was a handsome three-storied Georgian building with two ample side-wings, numerous outhouses, and paddocks at the rear end where his numerous brothers and sisters could ride their ponies. One of Frank’s first memories in childhood was falling off his pony into a very muddy ditch and being dragged out his feet first by his eldest brother.

Figure 1.1 A portrait of Charles Darwin (1809–1882) by George Richmond in the 1830s.

In that summer of 1828 when Frank first met Charles the Galton family was already large. Out of the 10 children, 7 had survived into late childhood. Frank had two elder brothers, and then came his four sisters. Frank was the baby of the family and excessively indulged by all his sisters, but especially by the third one, Adele—or Delly as Frank had called her from his early infancy. She greeted Frank’s birth as a fairy gift and begged hard to be allowed to consider him as her sole charge. His other sisters petted him as the baby but Adele always had the greatest share of his heart. Frank’s chief attractions as a child at that time were an imperfect articulation of English, an earnest desire of having his own way, many cunning tricks, and the source of a great deal of noise.1 Charles Darwin’s visit was really at the instigation of Frank’s father who was worried about the educational prospects of his eldest son Erasmus named after his grandfather. Charles at 19 years was already enrolled as a medical student at Edinburgh University and the father’s hope was that Charles’s visit might inspire Frank’s brother Erasmus to take up a similarly serious vocation. In reality, Charles appeared to spend more time with his insects than on his medical studies in Edinburgh.

They all used to take tea in the parlor, a high clean rather empty looking room at the back of the house. Frank’s mother asked Charles if he wanted to go riding with them on the following day. No—he would really rather go out walking by himself in the fields at the back of their estate. Charles loved riding but he had recently contracted a passion for collecting insects, particularly beetles. What workmanship there is in the frame of beetles; such as living watches concealing the thousand springs and cogs of life. He pulled a pillbox out of his jacket pocket to show them and Frank was astonished by the appearance of the insect. It was about the size of a Brazil nut with a shining brown carapace, just like the shell of a conker. It had white wiggly stripes going down to a most ferocious looking proboscis. Here were two pincers looking like fret-saw blades facing each other, and two long antennae extended similar to curved pylons from the base. Woe betides any unsuspecting smaller insect that accidentally strayed between the blades of this ferocious beetle; they would be instantly mashed into little pieces. Charles referred to the beetle by a villainous sounding Latin name that Frank did not understand.

Frank was overwhelmed after tea when he followed Charles, at a distance, into the rear of their estate by the river.

It was a pleasant countryside at that time with gentle hills, the woods were full of fine timber, and the valleys beyond were comfortable and snug with rich meadows, and several neat farmhouses scattered here and there. Sadly the town of Birmingham has now encroached on all this farmland. Charles was scraping at the bark of a rotting old tree by the riverbank. Two rather dull colored beetles scampered out from a crevice and were immediately captured by Charles. One fell to the ground onto its back and its legs struggled similar to an orchestra playing Beethoven. The other, a gigantic black beetle tried to escape and Frank was thrilled to see Charles place the smaller of the beetles into his mouth to free his hand to capture the giant. A few seconds later, he spat it out. He told Frank and the others afterward that the beetle had spurted out an acrid juice from one of its body glands that tasted foul.

Charles loved collecting beetles and other insects. He might even have died for his love of them. While in South America exploring the province of Mendoza on the Beagle expedition he was attacked by the aggressive black assassin bug. This is a species of reduviid insect, the vinchuca bug that lives in the roofing and thatch of local houses. It was the most disgusting thing to feel the soft wingless insect about an inch long drop down from the roof and crawl over your body at night, quite fearlessly darting at any exposed skin surface to suck blood. Charles rather foolishly caught one the next day and placed it on a table, and although surrounded by people, the bold insect charged at his bare finger brandishing its sucker to draw blood. The wound caused no pain and it was curious to watch the insect’s body during the attack change from wafer thin to a globular one bloated with blood. This may be linked to Charles developing a long chronic illness in midlife that caused palpitations, shortness of breath, and he intermittently suffered stomach disorders for the rest of his life. At the age of 33 years, he had gone on a long tour of North Wales to study the geological effects of the extinct glaciers that formerly filled all the larger valleys. This was the last time that Charles ever felt strong enough to climb mountains or to take such long walks that these expeditions required, due to his shortness of breath and giddiness. No proper diagnosis was ever made. Charles went for various water cures with variable results, but the general conclusion was that his symptoms were due to some form of hypochondria.

The doctors might have misdiagnosed him, because by the beginning of the twentieth century, it was found that the reduviid bug transmits an infectious parasite that lodges in the heart and the lining of the intestines. The main features of this parasitic infection, Chagas disease, fit like a hand-in-glove to all the symptoms that Charles developed. A patient with Chagas disease often has a dilated heart with failure of the circulation producing breathlessness and fatigue; the intestines are affected leading to severe indigestion and abdominal distension; and to this day there is still no completely satisfactory treatment.

Of course, Frank copied Charles in his passion for collecting insects, but extended his collection to seashells, minerals, and coins. The beetles were his treasured possessions. A last will and testament was found in an old trunk that Frank wrote at the “advanced” age of 8 years, bequeathing his insect collection to his dearest sister Adele. He left his mineral and seashells to another sister Bessy.2

In the following days of Charles’s visit, another incident occurred that had a big influence on Frank. His father had a scientific bent and as a banker had published a general paper on money supply, price level, and the exchange rate but without really clarifying the relationships that were involved. His great respect for science led him to collect all sorts of scientific instruments, although he probably could not tell you the difference between a theory, a hypothesis, or a concept and had no idea about the basic principles of scientific method. He collected objects such as antique telescopes, armillary spheres, and astrolabes, which were scattered around the house on shelves, taking the place of the usual domestic ornaments such as vases and porcelain figures. One highly prized instrument was an intricate eighteenth century vernier barometer housed in a beautiful inlaid wooden case. Charles wanted to examine it and Frank’s father took it off the wall and very patiently tried to explain how it worked. Frank was hanging around in the background keeping close to his older cousin. Frank did not understand how atmospheric air could weigh anything or how it could depress a column of mercury. The brass vernier scale was also beyond him. But the whole episode awakened a sense of mystery and delight in strange and exotic scientific instruments that remained with Frank ever after. As an adult Frank invented some instruments of his own and he tried to live his life by the scientific method. All aspects of his life were to be treated in the spirit of an experiment and to be measured, if possible. It provided a certain measure of detachment in his personal relationships. For example, if he approached an attractive woman at a social gathering, the encounter was treated as an experiment. How would it turn out? He remained as objective as any field observer and had no particular desire to see one outcome prevail over any other. He would just vary the conditions of approach at the next encounter to see if it would turn out differently. In the end, he invented an instrument to record the sexual attractiveness of all the women that he passed in the streets. He kept the instrument in his pocket and rated the women as they went by. He constructed a “beauty map” of the British Isles and found the least attractive women to be in Aberdeen; the most attractive were to be found in London.3

From Frank’s father’s point of view, Charles’s visit was not particularly successful. Frank’s brother Erasmus had nothing much in common with Charles. Indeed, they hardly spoke to each other during the whole stay. Erasmus was determined anyway to go into the Navy. However, the visit did succeed in influencing Frank; he wanted to copy what his cousin Charles was to do. Frank’s mother was also keen for her son to study medicine because her father had been a very successful medical practitioner and she hoped to see the profession carried on in the family. So, from an early age it was always to be medical studies for Frank too.

Mendel’s childhood was mainly spent on his father’s farm where he helped to tend the orchards and became very interested in bee keeping, to make honey. His interest in bees survived to his time in the monastery where he looked after batches of hives to produce honey for the brethren. In childhood there is no record of him having had any scientific mentors.

To be a doctor4

It was Darwin’s father who drove Charles to study medicine. You care for nothing but shooting, dogs and rat-catching; and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family, Charles was once told in a fit of irritation by his father. To avert this dire prognosis Charles was duly enrolled as a medical student at Edinburgh University. He only stayed in the course for 2 years. The subject was of intrinsic interest, but he found most of the lectures intolerably boring. There were long stupid lectures by a Professor Duncan on materia medica starting every morning at eight. They reminded Charles of the method used to detect excessive fluid that can accumulate in the abdomen by percussion of the stomach wall. The procedure is called listening for “shifting dullness,” which perfectly fitted the contents of the professor’s lectures. Then a Professor Munro lectured on Anatomy. Charles disliked him and his lectures so much that he could not speak with decency about them. The Professor was dirty and slovenly in person as well as in his behavior. It was not uncommon for him to enter the lecture theatre bedaubed with blood from his recent dissections and his teaching was very out-of-date.

The final straw came when Charles had to attend an operation on a small child. The little girl had fallen under the wheel of a cart on Princes Street and she had crushed her right foot. The foot had become infected and then gangrene had set in and now needed to be amputated. There was no anesthesia in those days. The child was just wrapped in a blanket to stop her struggling with her foot protruding at the lower end. She was laid on a bare operating table with small wooden tables at its side on which was assortments of surgical instruments neatly laid out in rows. They resembled the sort of tools one might find in a carpenter’s shop: large metal mallets, pincers, strong scissors, and ferocious looking handsaws. One thick metallic saw had deep notches along its cutting edge to trap any bone or flesh from clogging the blade as it sawed through the leg. The surgeon, with his assistants dressed in loose fitting white tunics with rolled up sleeves held the child down, while the chief surgeon commenced the amputation. The eager faces of the students, including Charles, were ranged at the back of the room. Speed was of the essence; if the whole operation could be completed in 10–20 seconds she would have a good chance of survival. The death rate from amputations at this period was about 50 percent. The surgeon started to see into the leg about four inches below her right knee. The crescendo of screams of the little girl was unbearable, eventually subsiding into deep sobs of despair as the child became exhausted. She never lost consciousness throughout the whole operation of about four minutes, but toward the end her cries seemed to be disconnected from the activity of the surgeon—God alone knows what she was really suffering. This horrible and cruel experience was enough to drive Charles completely away from any more medical studies. The cruelty was unnecessary. His cousin, Frank, as a medical student also saw an emergency amputation of both legs of a powerful drayman who had fallen under the wheels of a stagecoach. The man was virtually dead drunk when he was brought into the operating theatre and the amputations were started immediately. He felt nothing, and indeed was in a drunken sleep throughout the whole procedure. One wonders why they could not make all preoperative patients “dead” drunk, so they were spared the pain of the surgery. Anesthesia was a marvelous invention but did not come into standard practice until the early 1840s with laughing gas (nitrous oxide), then in the mid-1840s with ether, and eventually in 1847 with chloroform.

Charles spent more and more time in Edinburgh studying his beloved insects and made some very interesting and original observations on the habits of marine invertebrates. He joined the local Plinian society to present some of his findings. He met there Robert Edmond Grant (1793–1874) who was an Edinburgh-trained physician. Grant had given up medicine to study the evolution of invertebrates and had even cited Erasmus Darwin’s Zoonomia in his medical dissertation. During the Plinian Society’s joint collecting trips to the sea shore, the older Grant introduced Darwin to the world of research and microscopic dissection—and this led to the Darwin’s first scientific paper, delivered at the Plinian Society in 1827.

As Darwin later wrote in his autobiography, He [Grant] one day, when we were walking together, burst forth in high admiration of Lamarck and his views on evolution. I listened in quiet astonishment, and as far as I can judge, without any effect on my mind. Later in life, Darwin would distance himself from Grant, probably because of Grant’s radical views on the transformation of species following on from Lamarck’s ideas on the inheritance of acquired characters. Lamarck believed that if, for example, a father developed his musculature during his work as a blacksmith then his children would inherit as strong a musculature from him. Incidentally, Hippocrates antedated Lamarck’s views on the inheritance of acquired characteristics by writing characteristics thus acquired (referring to the custom of molding the heads of newborn infants to an elongated from the spherical form) at first by artificial means, but as time passes becomes an inherited characteristic so the practice… [of binding the head]… was no longer necessary.

Darwin dropped out of medical studies altogether by 1828.

Frank’s experiences studying medicine were quite different. He started at the Birmingham General Hospital in 1838 and rather enjoyed the charade of medicine. He particularly liked working in the dispensary. He became adept at making a variety of infusions, decoctions, and extracts of various herbs and minerals. He was never quite sure what good they did, so he started to try them on himself. He developed quite a taste for one particular decoction: a quart of aqua vitae, one ounce of aniseed bruised, one ounce of liquorice sliced, and half a pound of poppy seeds (from Papaver somniferum) all steeped for 10 days, after which the supernatant is poured off into a bottle containing two tablespoons of fine white sugar. It was meant to be a cure for asthma, but he found it quite a decent cordial after evening meals. He did worry afterward about how much...