![]()

1 Making up the boulevard

[The flâneur] has proven himself an attractive and suggestive figure, one conveying the peculiar features of life in the metropolis—fragmentation, anonymity, speed. I want to suggest that it will be no great loss to ask the flâneur to cede his central position and instead occupy a more marginal position as merely one of the city’s inhabitants.1

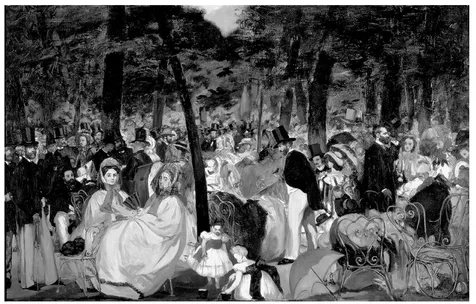

Manet’s Music in the Tuileries (1862; Figure 1.1) was exhibited in 1863, the same year in which Baudelaire published “The Painter of Modern Life.” The painting depicts a crowd of well-to-do Parisians enjoying a concert in the gardens of the Tuileries palace. Included among the faces of the countless anonymous concert-goers is a self-portrait of Manet as well as portraits of his friends and contemporaries, including Aurelien Scholl, Baudelaire, Jacques Offenbach, Mme Lejosne, and Mme Loubens.2 In noting the coincidence in timing of the painting’s exhibition and the publication of Baudelaire’s essay, several scholars have seen the canvas, with its blurred representation of Baudelaire on the left, as support on the part of Manet for the poet’s description of the flâneur as a dominating, gaze-wielding artist constantly on the move. Fer, for example, uses Manet’s painting in her discussion of the modern spectator/ flâneur to argue that the formal characteristics of the work—the sketchiness and the spatial inconsistencies—convey the movement of the crowd and the passing glance of spectators.3 The assumption in Fer’s argument, as well as in others that link the painting and the essay, is that the men depicted dominate the garden and, by extension, the boulevards of the city with their upright stances and penetrating gazes. In their efforts to make the painting’s gender dynamic “match” that in Baudelaire’s essay, however, scholars have hardly addressed the women depicted in the painting who are listening to the same concert under the same trees; the women have instead been dismissed by at least one scholar as part of the “feminine universe” of the decorative and curvaceous chairs.4 The fact that some of the men, including Offenbach and Zacharie Astruc, are seated in the “feminine” chairs and that numerous women are standing, some whose faces are out of focus in the same way as Baudelaire’s, has also been overlooked.5 It is this desire on the part of scholars to force the visual culture of the period to fit within the fictional framework of Baudelaire’s essay that is upended in this chapter; my re-reading of images, both canonical and not, attempts to move beyond Baudelaire’s gendered binary as it has been grafted onto Parisian visual culture.

Figure 1.1 Edouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries, 1862. Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 118.1 cm. The National Gallery, London, UK/Bridgeman Images

What Manet proposes in this painting in terms of gendered public space and the modern spectator has little to do with Baudelaire other than their obvious parallel interest in contemporary urban subject matter.6 Not only are the men and women in Manet’s painting occupying the public space of the garden in analogous ways, but the gaze that Baudelaire gives exclusively to the flâneur in his essay is, in Manet’s painting, possessed by several disparate figures, including the monocled man on the left, the two women in the foreground, and a beribboned lapdog, all of whom stare pointedly at the viewer.7 This radically dispersed gaze and the shared public experience of the depicted figures irrespective of their gender corresponds in no way to Baudelaire’s description of urban life in “The Painter of Modern Life,” where it is only the flâneur, certainly not well-to-do women, who occupies public space and possesses the gaze. Scholarly adherence to Baudelaire’s understanding of the urban outdoors has meant that neither bourgeois women nor men of the lower classes have had much role to play in the hallowed public spaces of modernity, particularly the boulevard. It is this scenario—more fantasy than reality—that I will confront in this chapter.

Despite the fact that Manet’s Music in the Tuileries refuses to support in any definitive way the presumed near-exclusive relationship between public space and masculinity as theorized by scholars based on Baudelaire’s essay, the painting continues to be used to uphold entrenched understandings of these concepts as mutually defining. In the 2006 exhibition Rebels and Martyrs: The Image of the Artist in the Nineteenth Century, for example, Manet’s work was hung in a section of the show entitled “Dandy and Flâneur.” In her review of the exhibition, Alison McQueen critiques this section for not adequately exploring the flâneur’s rootedness in the urban outdoors. McQueen points out that this portion of the exhibition, rather than highlighting the boulevard, focuses instead on “portraits of male artists either in their studio environments or posturing as gallant gentlemen . . . works that are not clearly distinct to the theme.”8 McQueen’s observations are apropos, for while Baudelaire specifically posits the flâneur as an artist, he just as specifically situates the figure in public space. Why, then, one might wonder, is Manet’s Music in the Tuileries the only painting in an exhibition specifically on the topic of the flâneur that could arguably be seen as showcasing the flâneur in his true milieu? This question is especially relevant considering that, as McQueen notes in a bit of understatement, the flâneur has “recently received scholarly attention.” In fact, the staggering amount of scholarship on the flâneur and his putative mutually defining relationship to the boulevard and public space more generally, not to mention the almost wholesale conflation of this figure with Parisian bourgeois men, would lead one to believe that the flâneur—i.e., lone, gaze-wielding, top-hatted men in public space—was ubiquitous in the visual culture of the period. Otherwise how would Baudelaire’s construct continue to dictate scholarly understandings of the gender and class dynamics of public space as well as our very definitions of masculinity and femininity? As the exhibition inadvertently reveals, however, figures that can be read non-problematically as flâneurs à la Baudelaire are almost nonexistent in the visual culture of late nineteenth-century Paris. While there are a handful of individual images that could be used to support Baudelaire’s concept of the flâneur, there is in no sense a consistent body of works on the subject. What the exhibition also makes obvious is that scholars have compensated for the dearth of flâneur figures in visual culture by turning instead to what I (and McQueen) argue are wholly inappropriate studio portraits and other genres in their explication of the theme and its supposed importance to understandings of bourgeois masculinity, gendered public space, the gaze, and even artistic creativity.

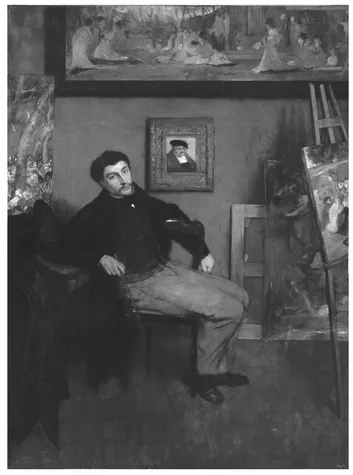

Herbert, for example, devotes a section to “The Artist as Flâneur” in his important and influential book Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (1988). In a chapter where one would expect to find numerous images of top-hatted flâneurs/ artists enjoying the crowds and spectacle on the boulevard at their leisure, Herbert instead employs a motley assortment of paintings to make his case, including a studio portrait, a family portrait, and a depiction of a woman on the boulevard. Degas’s James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot (c. 1867–68; Figure 1.2) is the first image to which Herbert devotes sustained attention in his exegesis on the flâneur in visual culture. His description of the painting is worth quoting at length:

Degas shows his painter friend as the dandy he was, a flâneur -dandy who has been out for a stroll, and who has dropped in on his friend for a moment . . . He puts his top hat and cape, carelessly but ostentatiously, on the table and gives a rakish angle to his stick, to emphasize his refined indifference . . . the twist of his upper body, and the drawn-in feet, reveal that he is on the qui-vive, ready to depart at a moment’s notice. Degas has therefore drawn a portrait of a flâneur by putting on show his refined casualness, his status as a stroller-visitor, his alertness—and by abstaining from the traditional psychology of expression . . . Tissot’s face shows no revealing emotion, but of course a flâneur and a dandy are properly characterized by seeming indifference. And Degas hints at his own aloofness, that of the artiste-flâneur, by sticking to externals, by refusing to become involved with his sitter.9

Figure 1.2 Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas, James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot, c. 1867–68. Oil on canvas, 151.4 x 111.8 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1939 (39.161) Photographed by Malcolm Varon

In Herbert’s account, almost every detail of the painting is attributed to Tissot’s or Degas’s status as a flâneur, including the missing leg of the easel which Herbert sees as an example of “wit suitable to the artiste-flâneur .” Is it not worth asking why, if Degas had wanted to depict a flâneur, the artist did not paint an image of Tissot on the boulevard or—at the very least—at a sidewalk café table? Why instead has he placed Tissot in the interior space of a studio with no access via windows or doors to the boulevard that, according to Baudelaire, was the flâneur’s rightful place—the defining element of his identity? What Degas gives us instead is an inactive man seated indoors with no means of egress, surrounded on all sides by paintings, none of which are obvious representations of the boulevard. This disconnect between Degas’s painting and the essay that is presumed to illuminate it, is symptomatic of scholarly attempts to fit images to this pre-existing Baudelairean paradigm.

One could perhaps reasonably expect to find images of the flâneur in Caillebotte’s oeuvre. The artist is known for his boulevard scenes and in scholarship on late nineteenth-century visual culture, his paintings, more than those by any other artist, have been associated with masculinity and how it is defined during this period.10 His 1876 Pont de l’Europe (Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva), which Herbert mentions in passing, could arguably represent a flâneur.11 The work depicts a Parisian boulevard in a recognizable location in the eighth arrondissement, which had been much altered during Haussmannization. People of both genders and various classes are pictured, but the artist’s focus is on a man walking through the streets in command of the space around him. The gentleman’s authority is evinced by his size; he is larger and closer to the viewer as well as to the center of the painting than the woman who walks slightly behind him. She is also in shadow and framed by the people who delimit the space around her. The sense of male dominance is heightened by the fact that the work is painted at street level. This vantage along with the vanishing point gives a strong sense of movement to the composition so that the viewer feels part of the bustling boulevard, almost as if s/he is in the path of the strollers. Along with Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877; Art Institute of Chicago), the work is one of Caillebotte’s best known. The reputation of these two paintings is not coincidental, however, as both exemplify to varying degrees Baudelaire’s flâneur and thus conventional scholarly characterizations of bourgeois masculinity as dominating the boulevards and public spaces of the city.12 It is notable, however, that such paintings in which bourgeois men who can be read easily through the rubric of Baudelaire as dominating, gaze-wielding flâneurs on the boulevards are rare even in Caillebotte’s oeuvre, which is filled instead with images of men in interior spaces or in provincial settings far from the boulevards of Paris.13 Paris Street, Rainy Day and Pont de l’Europe are the closest the artist comes to representing the mythical flâneur “amid the ebb and flow of movement . . . at the center of the world.”14 Neither of the paintings is non-problematic in this sense, however, as both show men accompanied by women.15

If the flâneur—or, at least, male figures who can be read as such—is all but absent from the visual culture of the period, whence this desire on the part of art historians to promote Baudelaire’s construction, to imagine an importance for the ...