Curtain Lectures: Sites and Women’s Speech

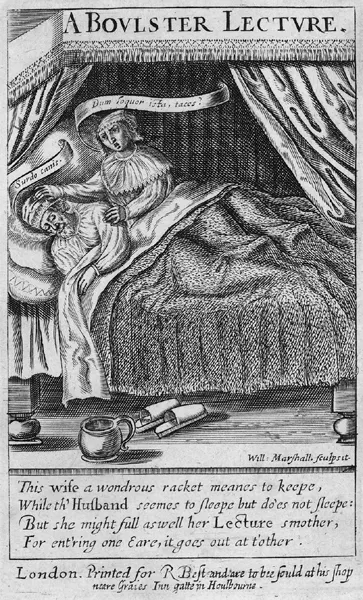

In non-dramatic representations, the most notable feature of curtain lectures is their location: Heywood illustrates his A Curtaine Lecture with a woodcut of a wife speaking to her husband within a curtained bed. The location of the woman’s verbal disturbance, in public as opposed to private spaces, is essential in distinguishing between the terms “shrew” and “scold,” between being a nuisance and a criminal. Location is also important in defining the curtain lecture. In addition to being a metonymic reference to the bed, the curtain lecture is named after that which demarcates the bed-space.7 Drawn curtains mark the boundary between the public and private spaces of the early modern bedchamber. The curtain lecturer is a woman who is seen as speaking to her husband, but in private, and in a space that is intimate and sexualized, the bed.

The bed was part of public as well as private life in early modern England. Sasha Roberts notes that the bed was “a uniquely important possession within the early modern household for its role in the major rites of passage in men’s and women’s lives; rites that are crucial to the formation of patrimony: marriage, birth and death” (155). Family and friends shared in one such ritual, termed a “bedding ceremony.” At the end of the bedding ceremony, “the wedding guests wished the bride and groom well, drew the bed-curtains, and left the couple to consummate their marriage in private” (156). The bed was recognized by the couple and the community to which they belonged as an important symbol of marriage: “Precisely because the bridal bed was the focal point of the wedding ceremony it gained considerable symbolic power, and after the ceremonies were over the ‘marriage bed’ became a potent emblem of a couple’s marriage; a marker of the fact of marital sexuality” (156–57).8 While the bed was the centerpiece of this publicly witnessed ceremony, it was also a private site; the curtains, which could section off the bed from the rest of the room, marked this private dimension. Philippe Ariès adduces the fact that “now people began to reserve a special place for the marriage bed” in support of his argument for the rise of privacy in the Renaissance.9 While privacy might have been on the rise during the early modern period, Lena Cowen Orlin notes that “Private is a relative term when the presence of a servant’s pallet meant that the highest degree of somnolent and sexual seclusion in the early modern household expressed itself solely and by our lights inefficiently through the drawing of bedcurtains. Thomas Heywood emblematizes spousal intimacy in titling his economic treatise A Curtaine Lecture, for this token of privacy” (185). The curtains on a bed might fail to secure what modern commentators might consider true privacy for the couple inside, but drawn curtains indicate that intruders are not welcome.10 Roberts adds that “because the bed was generally the largest single item of household furniture, carving out with its posts, ceiling and curtains an intimate space within the bedchamber, it afforded a level of privacy that set it apart from other pieces of domestic furniture” (157). While the closed curtains might suggest a mere hint of privacy, drawn curtains mark the separation of the bed as private space from the bedroom’s more public functions.11

In addition to being at the center of marriage rites, the bed was also the site of birth and death. Childbirth made the bed a domain for women only, as they assisted with the birth and supported the mother. The bed space would be altered for this event: “air was excluded by blocking up the keyholes; daylight was shut out by curtains; and the darkness within was illuminated by means of candles… . Thus reconstituted, the room became the lying in chamber” (Wilson 26). In death the bed would also be at the center, for in the case of household deaths the dying would lie in bed and from their beds speak their final words. One famous dramatic example is the “tragic loading” of the bed at the end of Othello. As Michael Neill observes, Shakespeare emphasizes the fact that Desdemona is murdered in her bed.12 In non-dramatic examples, the bed is commonly the site of a less violent passing. For example, after the Viscountess Montague, Lady Magdalen, fell “into a palsy,” she “lost the motion of the right side of her body and much wanted the use of her tongue” (38). She remained in this state for eleven weeks, during which she presumably did not leave the bed, until she delivered her final words after waking one morning: “‘Into thy hands (O Lord) I commend my spirit” (43). Her minister records what words she was able to speak to her servants and family.13 Catherine Richardson, discussing the bequeathing of household objects in wills, notes that the bed of the benefactor is often identified with the phrase “which I now lie upon,” suggesting that “the deathbed scene offers a conventional image” (74). The bed provided the setting for central moments in the lives of early modern English people and was accordingly transformed from the woman’s domain of the lying-in chamber to the familial site of the deathbed; between these moments, it was the province of husband and wife.

Evidence from many sources, including early modern diaries, suggests that the bed was also considered a site of marital struggle or familial upheaval.14 Ralph Josselin records in his diary on May 9, 1647, that “this weeke my wife weaned her daughter Jane, shee tooke it very contentedly, god hath given mee much confort in my wife and children, and in their quietnes, which hath made my bed a rest and a refreshing comfort unto mee” (93), indicating that he expects his bed to be a sanctuary from the noises of his busy household.15 Jane is not his first daughter, however, and the wording of this entry suggests that his bed is not always such a site of rest and comfort, though it is now “made” one. Did earlier children, or his wife before she was a mother, make this bed less of a comfort? Josselin does not say, though he does include a story of one couple that tied their disagreements to the bed indeed. He writes on January 21, 1658: “R.A. with mee, he told mee how his wife kept him bound in bed to force him to sell his lands” (416).16 The cautious Josselin, whose diary appears crafted for later public viewing, affords himself little room to critique these actions, though his few words indicate that at the very least he is relieved not to have such a wife himself. His only comment is: “well its a mercy to bee kept upright in our wayes, and delivered from unreasonable persons. I suspend my thoughts in such matters” (416). Presumably the wife is the unreasonable person in this scenario. Her use of the bed, Josselin’s desired site of “rest and … refreshing comfort,” to force her husband to acquiesce to her will marks her as “unreasonable.”

Like the example from Josselin, Samuel Pepys’s diary suggests that well into the seventeenth century curtain lectures were a useful tool for wives attempting to tame unruly husbands; reading Pepys’s entries further demonstrates the practical features of a curtain lecture. Pepys writes in his diary of his sexual exploits with his wife’s servant, Deb Willit, and his wife’s resulting curtain lectures.17 During the aftermath of the affair, Mrs. Pepys uses the bed she shares with her husband as the site for airing her grievances. As Mr. and Mrs. Pepys sort out the affair, Pepys spends many restless nights listening to his wife, prompting him to remark: “And so to bed—where my wife mighty unquiet all night, so as my bed is become burdensome to me.”18 Only through “good words and fair promises” made to his wife, along with many conciliatory gestures, including firing Deb and later writing her a letter in which he calls her a “whore,” is Pepys able to regain restful nights of sleep.19 It is practical for Mrs. Pepys to use the bed as a site for talking over the Willit affair with her husband, for it is the only place in the house in which they are alone. Initially, Willit was living in their household, and it was only after several weeks of sleepless nights that Pepys made Willit leave his home. By turning her bed into a battleground, Mrs. Pepys is able to make her weary husband succumb to her will.

An early discussion of the curtain lecture that suggests parameters for use of the marriage bed in order to avoid such “abuses” occurs in Desiderius Erasmus’s colloquy “A Mery Dialogue,” which was first printed in Latin in 1523 and later translated into English in 1557. “A Mery Dialogue” discusses curtain lectures and suggests parameters for use of the marriage bed; these discussions connect a wife’s verbal and sexual behaviors.20 The text contains a dialogue between Eulalia and Xantippa, a character named for Socrates’s famously shrewish wife. Xantippa’s self-described problem is that when she speaks to her husband she “spare[s] no tonge” and he in turn responds with “his crabid wordes” (249). Eulalia tries to show Xantippa how to be a good wife by sharing many stories of wives. Eulalia advises Xantippa that when a wife must approach her husband about a problem, she should wait for the appropriate time to speak. Her husband should be “ydle” and the speech should be held “betwixt you two secretly” (258). Eulalia adds another set of restrictions. She tells Xantippa to take care in particular “that thou never gyve hym foule wordes in the chambre, or inbed,” for that is a site for “pastyme and pleasure” (271). It is an error, she says, if a place which is “ordeined … to renew love, be polluted eyther with strife or grugynges” (271). The parameters of acceptable wifely speech have shrunk considerably: the wife should wait until she is in private with her husband, but this location must not be in b...