1 Mainstream parties, the populist radical right, and the (alleged) lack of a restrictive and assimilationist alternative

Pontus Odmalm and Eve Hepburn

Introduction

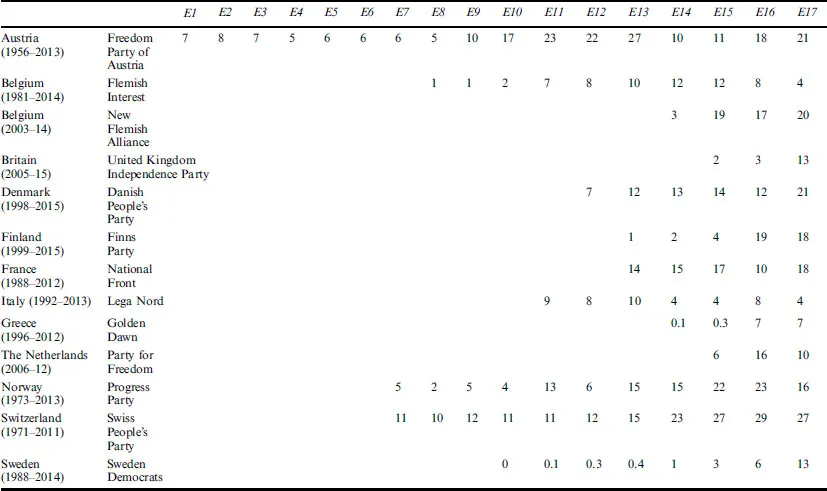

The populist radical right (hereafter PRR) is now a semi-permanent presence in several West European parliaments (Mudde, 2013, 2010; Rydgren, 2008). The parties belonging to this ‘new’ family have a multitude of origins but also share some important characteristics (Zaslove, 2009; Kitschelt, 2007; Minkenberg, 2000). Some started out as anti-authority and anti-red tape parties (Taggart, 1995) only to adopt increasingly authoritarian and conservative positions in recent years (McGann and Kitschelt, 2005; Kitschelt and McGann, 1995). Nationalism, welfare state chauvinism, and promises of a draconian approach to the immigration ‘issue’ have thus moved up on the parties’ electoral agendas. Yet elsewhere immigration and integration have constituted prolonged features of their election campaigns and party identities (De Lange and Art, 2011; Karamanidou, 2014; Goodliffe, 2012). As Table 1.1 shows, the PRR has been a feature of European parliaments since the mid-1950s. Austria and Norway are distinct outliers in this respect, there having been such a significant presence for more than forty years, whereas in Sweden, PRR-type parties have been largely absent, notably at the national level. One can also observe a clustering of cases. On the one hand, the PRR increased – and largely consolidated – its share of the vote in several countries. On the other hand, it has also experienced several electoral ‘dips’, particularly in Italy, the Netherlands and Norway.

Table 1.1 Results for the PRR, 1956–2015 (%); elections at the national/federal/presidential level

Note: E = election.

The PRR has thus moved away from the niche position and entered the political mainstream, not least if ‘mainstream’ is measured by electoral support and seats in parliament rather than by ideological orientation, issues raised or solutions proposed. The literature points to a combination of supply-and-demand factors which has facilitated this transition while also contributing to the state of flux (Mair, 1989) many West European party systems are said be in. Mudde (2004) stresses the role of the PRR as demagogues and opportunists, which very much taps into prevailing dissonances between elite ‘aims’ and electoral ‘wants’. This gap, whether perceived or real, as well as voters’ increased dissatisfaction with the way in which their country is run, highlight the ‘populist’ aspect of these parties, and how the only ‘common sense’ option lies with the PRR contender (Zaslove, 2004).

Yet Betz (1993, see also Evans, 2005) suggests that the PRR’s success also connects to a ‘politics of resentment’, which has become increasingly consolidated across Europe. Mainstream parties, the argument runs, have effectively lost touch with ‘the man on the street’ and they have not responded sufficiently – or even quickly enough – to the concerns expressed by a ‘forgotten working class’ (see further Grabow and Hartleb, 2014; Oesch, 2008). The PRR’s ‘radical’ tag, and its tendency to offer solutions traditionally associated with parties to the mainstream right, further highlight the metamorphosis that these parties have gone through. Several authors note that growing – and increasingly diversified – levels of migration have contributed to the (re)emergence of chauvinist sentiments regarding legitimate access to the welfare state, to the national labour market, and to the benefits associated with being a citizen (see e.g. Mudde, 2007; Minkenberg, 2000). Yet a key feature of contemporary PRR parties is that they often portray themselves as the only viable choice for those voters wishing for a significant reduction in numbers or even a complete halt to the arrival of certain migrant categories (see e.g. Akkermans, 2015; Helbling, 2014; Zúquete, 2008). Furthermore, they profile themselves as the sole actor to emphasise assimilation and reject (most) multicultural policies (Koopmans and Muis, 2009; Zaslove, 2008). Elsewhere, van der Brug et al., (2005) suggest that such socio-structural and protest vote explanations to have limited explanatory power as their findings highlight prevailing opportunity structures to be better predictors for the success of PRR-type parties.

Yet the above explanations also downplay the role that mainstream parties play in this process, and, in particular, whether the lack of a restrictive and assimilationist (hereafter R/A) alternative can satisfactorily account for the PRR’s upward trajectory in recent years. Although some studies find that mainstream parties are less polarised than they perhaps used to be (see e.g. Bucken-Knapp et al., 2014; Super, 2014; Widfeldt, 2014; Schmidtke, 2014), this directional consensus is also under increased pressure from the PRR and a more volatile electorate. As such, mainstream parties are subjected to various prompts to accommodate the niche position and the restrictive views of the electorate (Art, 2011, Givens, 2005, Ignazi, 1996). Such pressures point to the fact that conventional narratives may no longer be entirely accurate and they therefore might warrant a more detailed investigation (see further Lahav and Guiraudon, 2006; Perlmutter, 1996).

This edited volume thus empirically addresses the significance of mainstream party positioning in affecting the success of the PRR. More specifically, it seeks to challenge those conclusions which suggest that the PRR option is, in fact, the only alternative for voters whose preferences fall in the reductionist and/or assimilationist spheres. The book utilises, but also expands upon, Meguid’s (2005) framework for depicting mainstream party responses to niche challengers (see also Bale et al., 2010). Meguid argued that one of three strategies can be used to counter the electoral success of the PRR, namely accommodative, dismissive, or adversarial approaches.

We have applied these approaches in order to further probe relationships between mainstream and PRR parties. But we have also moved beyond Meguid’s influential framework. We not only consider how the mainstream responds to PRR-type challengers but also how they respond to each other. That is, we wish to discover degrees of mainstream convergence compared to those stances taken up by the PRR. And how might this consensus – or dissensus – either advance or impede the PRR’s electoral success? We believe that Meguid may have been too deterministic regarding the potential responses that mainstream parties can make. We have therefore made a two-fold exploration. The first addresses the way in which mainstream parties have negotiated the strategic choices made available to them in the face of an increasingly successful – and anti-immigration – challenger. We then investigate the broader party system dynamics. It could well be that parts of the mainstream take up certain positions in response to their ‘normal’ competitors rather than them being instinctive reactions to the electoral threat posed by the PRR (Green-Pedersen and Odmalm, 2008). This more comprehensive focus allows us to challenge traditional explanations in the field, namely that ideological – rather than positional – convergence is key for explaining the PRR’s success (see e.g. Arzheimer and Carter, 2006).

Given that our aim is to assess the degree of choice offered by the parties, a key source of data is their respective manifestos. Basing the analysis on what is largely a blueprint for parties’ campaign priorities has enabled us to identify the differences in intended outcomes that these actors had in mind. The book then considers whether any changes in support for the PRR are also reflected in the positions that mainstream parties adopted from one election to the next. As such, our intention is to map cases where the PRR has been particularly successful, and then to track any positional changes that the political mainstream has effected over time. These stances have been systemically coded in order to initially establish the aggregate stances parties hold. They are then broken down to identify positional differences among three key sources of newcomers – namely labour migrants, asylum seekers, and family reunification migrants – as well as among parties’ preferred mode of integration (multicultural or assimilationist). This subsequently allows us to assess how much (or how little) choice was offered to the electorate.

Based on the above literature, then, we initially made three predictions. First, in those cases where support for the PRR has increased or consolidated over time, the data should reveal a congregation of liberal/multicultural positions (hereafter L/M). In other words, mainstream parties are assumed to have taken up ‘adversarial’ positions in response to the niche contender’s success. Conversely, when there are signs of declining support, a second expectation is that mainstream parties have changed positions in the R/A direction in order to remedy this electoral ‘theft’ (Van Spanje, 2010; Adams and Somer-Topcu, 2009; Budge, 1994). Such an outcome would thus constitute an ‘accommodative’ strategy according to Meguid’s framework. A third scenario is that the mainstream has not addressed the immigration issue at all, which consequently would be a ‘dismissive’ strategy. However, given the extent of public concern about immigration and integration ‘failures’, we assumed this to be an unlikely response. But should the data not support these premises (that is, adversarial, accommodative, or dismissive strategies) then the results needed further probing. We therefore asked contributing authors to pay special attention to whether any positional congruence – or divergence – can on their own provide enough evidence to explain variations in the PRR’s electoral fortunes (see further van der Brug et al., 2005; Arzheimer and Carter, 2006; Kitschelt and McGann, 1995).

Whether a choice matters or not has troubled political scientists for quite some time now. And this has become particularly relevant to address if party competition has moved into the realms of valence contestation (see e.g. Odmalm and Bale, 2015, Clark, 2009; Green, 2007; Bale, 2006; Stokes, 1963). But if so, then it arguably suggests how merely offering a choice might not always be enough. Competing parties might also need to convince voters that their ‘choice’ is better than that offered by their opponent/s, and equally they may need to evidence some form of track record of handling the issue/s at stake. The political mainstream could also suffer from a lack of trust regarding the way in which they managed the migratory flows and/or dealt with issues relating to socio-economic and cultural integration.

However, additional variables are likely to be at play. One relates to the degree of ‘agenda friction’ that exists between parties and the electorate (Schattschneider, 1960, see also Hobolt et al., 2008; Jones and Baumgartner, 2005). That is, mainstream priorities may not necessarily correspond to voters’ concerns, which the PRR contender, conversely, is quicker to calibrate and home in on (see e.g. Heinisch, 2010; Lahav and Guiraudon, 2006; Minkenberg, 2001). It could thus be more important that questions relating to immigration actually dominated on parties’ agendas rather than whether they offered an R/A choice (or not). Another aspect concerns the contagion effect (Norris, 2005) that the PRR is said to have. But as immigration and integration have developed into increasingly securitised – and increasingly murky – issues, mainstream parties may hesitate to deviate too far away from their long-standing positions, fearing a further haemorrhaging of votes and a further destabilisation of the party system. A third possibility posits that mainstream parties may also be hesitant to act as ‘issue entrepreneurs’ and who would stress issues previously suffering less prominence or salience (De Vries and Hobolt, 2012).

While our primary objective is to establish the degree – and type – of choice offered and then to assess whether the PRR option is, in fact, the only alternative, it is reasonable to assume that the above considerations and party strategies are also present. The contributors to this volume have therefore been given a degree of flexibility in order to capture some of the more contextual factors that may also help us to explain the outcomes established in Table 1.1. This leads us to three hypotheses which the book seeks to address:

H1: There are no differences between mainstream parties regarding their positions on immigration and integration.

H2: In the event that no mainstream party offers a more R/A position then the chances of success for the PRR increases.

H3: The PRR’s success is due to strategic miscalculations made by the political mainstream (i.e. inability to claim issue ownership; degree of agenda friction present; fear of contagion from the right; and/or slow to act as issue entrepreneurs).

Case selection rationale and time frame cove...