![]()

Part I

Functionally Embodied Culture

![]()

1 What’s Wrong with Organizational Culture?

On April 1, 2014, IMCO,1 a nearly 100 year-old diversified manufacturer of highly engineered components and technology for the energy, transportation and industrial markets, held a three-day Leadership Summit for its top 200 managers at the Ritz Carlton in Battery Park, New York City. This was a significant moment in IMCO’s history. Never had this company sponsored an event solely dedicated to shaping its own culture. As a consultant working with the company for over five years, I felt privileged to be invited.

IMCO was founded in 1920. During the 1960s and 1970s the company was known as the quintessential conglomerate, acquiring hundreds of companies across different industries, from telecommunications to casinos. Over time, the company divested, and in 1995 spun off its non-manufacturing divisions. In 2011 the company split itself into three: one focused on technology for the defense market, one on water treatment and transport and related technologies, and one retaining the IMCO brand focused on industrial technology. This ‘new’ IMCO went from a $12 billion, multi-industry conglomerate with close to 25,000 employees to a ‘$2 billion start up’, as IMCO managers like to characterize it, with 9,000 employees, sales in 120 countries, and operations in 35.2 As stated in the IMCO Factbook:

IMCO makes products and technologies that make other products operate:

Our goal is to make an enduring impact on the world. While many of our products operate in the background as part of larger systems, they are essential. Cars stop, planes fly, factories run, cell phones ring, and computers hum—all because they use critical components from IMCO.

(IMCO Corporation, 2014)

Conglomerates are characterized by diversification of assets in attempts to deliver better financial returns (Smith & Schreiner, 1969). They are not known for investments in human resource management (HRM) or culture; indeed, when construed as a portfolio of independent companies and brands, there is little need to integrate products, technologies, operations, or people. As such, the Leadership Summit represented a major event for this new entity, an opportunity to talk about and champion what the company aspired to become as a newly independent, smaller and more focused enterprise.

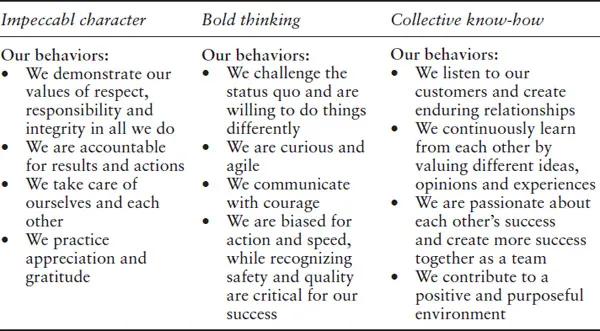

Through many hours of multi-media events, speeches, and breakout sessions, IMCO executives unveiled what they had been working on: the values and norms associated with a new aspired ‘culture’. The event was prompted by recent employee survey results that showed significant morale issues as many employees felt overworked and under-valued. The new cultural ‘behaviors’ (Figure 1.1) were thus targeted at changing how people in the company should behave.

Culture ‘Shaping’

The new cultural behaviors were part of a comprehensive culture-‘shaping’ program. Designed by a consulting firm retained to lead this effort, the Leadership Summit was the unveiling of work begun a year earlier with the employee survey and focus groups, followed by meetings with executives to present the survey results and define the new aspired values (see Figure 1.1). The Summit allowed me to witness first-hand what culture shaping, or “value engineering” (Martin & Frost, 2011, p. 602) looks like in action.

IMCO’s culture-shaping program, drawn from the marketing material of the culture consultant, is described in Table 1.1. Accompanying it is a list of assumptions upon which this program, and others like it, is based.

Figure 1.1 New cultural behaviors, IMCO.

These assumptions can be said to represent the mainstream view of organizational culture and change as taught and practiced in the United States and Europe.3 The basis of these assumptions is that ‘getting your culture right’ is a prescription for business success. What is curious about this view is that the cultural and cognitive anthropology literature, arguably the one discipline that puts culture at the center of its intellectual agenda, has very little to say about culture ‘shaping’.

Normative Control

Organizational norms, values and ideologies were first referenced in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and organizational culture as a construct has been a direct focus of inquiry since the 1970s. This in part can be attributed to a general interest in normative, or ‘Theory Y’, management that appeared in the 1960s as an antidote to the traditional ‘Theory X’ approaches (McGregor, 1960). The assumptions of the traditional approach were that people inherently dislike work and are unmotivated, thus control, coercion, and close direction is needed to achieve organizational outcomes. In response, Theory Y held that creative capacity of people in organizations is underutilized. Most people seek autonomy and responsibility and want to exercise creativity and imagination in problem solving. Theory Y shifted the focus from top-down to normative means of control, and with this came a corresponding interest in corporate culture (Kunda, 1992). However, underneath this new orientation remained an unstated assumption of managerial agency and control. The shift from overt to more indirect or covert forms of control retained the presumption of control. This is one reason why managerial control remains to this day an (unspoken) assumption underlying popular conceptions of culture.

Table 1.1 Culture change model espoused at IMCO | Culture and change model espoused at IMCO | Underlying assumption(s) |

1 Culture is a source of competitive advantage | Values such as collaboration, agility, accountability, innovation characterize a ‘high performance culture’. |

2 Culture can be ‘shaped’ | • Cultures are unitary wholes. • Culture is normative behavior. Norms can be ‘engineered’ by leaders for a positive outcome. This starts with establishing ‘core principles’. |

3 Culture change must be ‘led from the top’ | • ‘If change does not start from the top, the effort will fail’. Leadership must be ‘purposeful’ and entirely committed to the culture change. • Top leaders must ‘internalize’ the change. |

4 Culture change requires new behavior | • People change through ‘insights’ that come from their own experience. • In order to change culture, people must have a ‘profound’ experience of the new culture. |

5 Culture change must happen quickly | • ‘The faster people are engaged in the process of culture change, the higher the probability the culture will shift’. • The change effort must reach every employee in 10–12 months. • Leaders must be active and involved. |

6 Culture change must be reinforced to be sustainable | ‘Systematic reinforcement’ is needed at all levels of the organizational system (individual, team, organization). All ‘institutional practices, systems, performance drivers and capabilities’ need to drive toward the desired change. |

While organizational culture has remained a focus of research since the 1970s, beyond what I call the culture ‘industry’—management consulting firms and organizational development (OD) practitioners—there remains little consensus on what culture is or whether it can be managed, and, if so, how. Researchers and practitioners still disagree on even the most basic questions: What is culture? Is it something an organization has or something an organization is? Can it be measured, and, if so, on what basis? Is there relationship between culture and business performance, and, if so, what is it? Is it something management can impose, or is it somehow a part of all organizational actors? (Alvesson & Svenignsson, 2008; Martin, 2002; Smircich, 1983; Testa & Sipe, 2011). The Economist (2014) is one of the few in the mainstream business press to point out the difficulties in attributing causality to culture, admitting the term is so vague that “culture based explanations are often meaningless” (January 11, p. 72). Yet despite these questions, culture-shaping projects like IMCO’s proceed unchecked and unburdened by epistemic doubt. Managers and practitioners impugn cultural explanations for much of what constitutes organizational behavior in organizations, and, moreover, believe culture can be engineered to their own designs for positive business outcomes, no matter what the academic research may say.

What explains this gap between theory and practice? I suggest there is a relatively straightforward explanation. Managers are correct in suspecting culture is a powerful normative force, but current theory is unable to adequately account for it. This does not relieve managers and practitioners (or the popular media) of culpability for wasting resources when they carry out ‘quick fix’ culture change programs using watered down constructs based on little more than anecdotal evidence, projections of espoused values, or wishful thinking. At the same time, managers may be more sophisticated in their understanding of culture than is appreciated (Ogbonna & Harris, 2002). Rather, the lack of academic consensus is a result of the fact existing theory and research is unable to provide adequate answers to even the most basic questions on culture such as those posed above. Nor is it able to account for why some discourses, symbols, ideologies, and so forth become compelling to actors in some cultural and social systems, and others do not (Strauss, 1992). Simply put, despite many decades of work there is much about organizational culture we have yet to learn. Until better explanatory frameworks are developed, the gap between theory and practice will remain.

In this chapter I examine the principal reasons for this gap. I attempt to explain why culture theory is as impoverished as it is. I begin with a review of the current state of culture research, focusing on problems in both objectivist and subjectivist approaches.4 I then discuss how these issues impact culture practice, and examine the issues inherent in popular approaches to culture. I end by offering how a functionally embodied alternative to culture provides a way to reconcile divergent approaches while providing a more robust explanatory framework that accounts for the full range of cultural experience in organizations.

1. The Objectivist–Subjectivist Divide

The organizational culture field is characterized by a struggle for intellectual relevance, a struggle Joanne Martin and Peter Frost (2011) labeled the “culture wars” (p. 599). The culture wars cleave on the debate between an objectivist, rationally known world and an arbitrary, subjectively known one, a debate traceable to Descartes and Kant that has caused some anthropologists to abandon the concept of culture altogether (Strauss, personal communication, August 23, 2014; Descola, 2013). On one side are the objectivists, mostly economists, industrial-organizational psychologists and quantitatively oriented social psychologists who approach culture empirically, treating it as a variable to be measured, managed and leveraged.5 There is also a long tradition in anthropology of quantitative assessments of culture for the purposes of creating cultural typologies and cross-cultural comparisons, traceable to the work or Franz Boas and E.B. Tylor in the early 20th century (Jorgensen, 1979). This approach tends to put forth empirical ‘evidence’ of culture change by positing culture as one or two dependent variables, such as values or beliefs, and then providing statistical evidence of the state change of those variables. This research has been criticized for being overly reductionist, etic, and stuck in ‘paradigm myopia’, and yet remains immensely popular, with old and new culture diagnostics, measurements and typologies being invented and invoked with frequency (Baskerville, 2003, p. 5; Martin & Frost, 2011).6

On the other side are the “troublemakers” (Alvesson & Skoldberg, 2009, p. 3), subjectivists who challenge objectivist theoretical foundations and methods, and instead locate culture exclusively in symbols (public forms), texts and utterances (semiotic forms), artefacts and other “public phenomena” (Geertz, 1973; Shore, 1996, p. 51). Most culture research in this tradition offers little of pragmatic relevance for the practitioner or executive, which undermines its valuable contributions to methodology and its focus on the cultural subject.

Objectivist Approaches

There is an important need for verifiable and generalizable knowledge about culture in organizations. Nonetheless, objectivist approaches tend to suffer from issues related to ontology, epistemology, and ideation.

Problems of Ontology

We perceive social categories such as culture existing naturally in the world. As the social historian William Sewell Jr. (2005) puts it, this tendency “ontologizes” culture, giving it the appearance of being something naturally occurring (p. 349). Social categories such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A), for example, are imbued with pervasive power by metaphors such as FIGHTING, MATING or EVOLUTIONARY STRUGGLE. Such metaphors, embedded in multiple narratives, reify the sense that social phenomena such as mergers really are a struggle to evolve (Koller, 2005).

This phenomenon is aided by a major feature of human cognition, analogical reasoning, which enables thinking about abstract things by analogy to physical things (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, 1999). Our language reflects this through the many metaphors we use to talk about culture, metaphors that over time become so conventi...