eBook - ePub

From Sepoy to Subedar

Being the Life and Adventures of Subedar Sita Ram, a Native Officer of the Bengal Army, Written and Related by Himself

James Lunt, James Lunt

This is a test

Share book

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Sepoy to Subedar

Being the Life and Adventures of Subedar Sita Ram, a Native Officer of the Bengal Army, Written and Related by Himself

James Lunt, James Lunt

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

British military history in India has been amply documented, but From Sepoy to Subedar by Sita Ram is the only published account by an Indian soldier of his experiences serving in the East India Company's Army. These memoirs cover a span of more than forty years of active service, and provide a fascinating insight into the lives of the Indian soldiers serving under the British.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is From Sepoy to Subedar an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access From Sepoy to Subedar by James Lunt, James Lunt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

'. . . and relate the wonders of the world he had seen'

1 The Beginning

In this chapter, which in the Hindi version began with a long invocation to the Hindu gods, Sita Ram tells of how he became a soldier, despite the opposition of his mother and the family priest, Pandit Duleep Ram. It was his mother's brother, Hanuman, who fired him with ideas of military glory. Hanuman ivas a native officer (Jemadar1) in the East India Company's Bengal Army, and Sita Ram mentions the gold beads worn by his uncle in uniform. These were a mark of distinction, native officers wearing one row of gold beads, and the sepoys three rows of white beads. Sita Ram refers to the East India Company as. the Company Bahadur, meaning all-powerful. He also refers to it sometimes as the Sirkar, or government.

Sit a Ram was a Brahmin, the highest Hindu caste, and he was therefore subject to the strictest religious observances which, as will be seen later, greatly complicated his life as a soldier. His father was a yeoman farmer of comfortable circumstances who lived in the village of Tilοwee, in the Rae Bareli district of Oudh, in what is now the State of Uttar Pradesh (UP). Tilowee lies roughly midway between the cities of Lucknow and Allahabad in the very heart of Hindustan.

At the time of Sita Ram's birth, Oudh was an independent kingdom with its capital at Lucknow, and it was from Oudh that the East India Company recruited the bulk of its soldiers for the Bengal Army, and a lesser number for the Bombay Army. It had originally been a Mughul province, ruled by a Nawab appointed by the Emperor, but the Mughul empire was fast disintegrating by 1797, when Sita Ram was borti, and viceroys of provinces had set themselves up as independent princes. The notorious misgovemment of Oudh led to its annexation in 1856 by the East India Company, resulting in much discontent among the soldiers enlisted from Oudh who lost under the Company the valued privileges they had formerly enjoyed in the civil courts when Oudh was independent. The annexation of Oudh by Lord Dalhousie was one of the contributory causes for the Indian Mutiny in 1857.

I was born in the village of Tilowee, in Oudli, in the year 1797. My father was a yeoman farmer, by name Gangadin Pande. He possessed about 150 acres of land which he cultivated himself. My family when I was young were in easy circumstances, and my father was considered a man of importance in our village. I was about six years old when I was placed under the care of our family priest, Duleep Ram, in whom my father and mother placed implicit confidence, and they never did anything of importance without his advice and consent.

By him I was taught to write and read our own language; also a slight knowledge of figures was imparted to me. After I had acquired this I considered myself far superior in knowledge to all the other boys of my age whom I knew, and held up my head accordingly. All other castes were far below my notice. In fact I fancied myself more clever than my preceptor Duleep himself, and if it had not been for the high respect he was held in by my father, I should on some occasions have even dared to tell him so. Until I was seventeen years of age I attended my father in the management of his land, and was entrusted to give the corn to the coolies he sometimes employed in cutting his crops, drawing water, and so on.

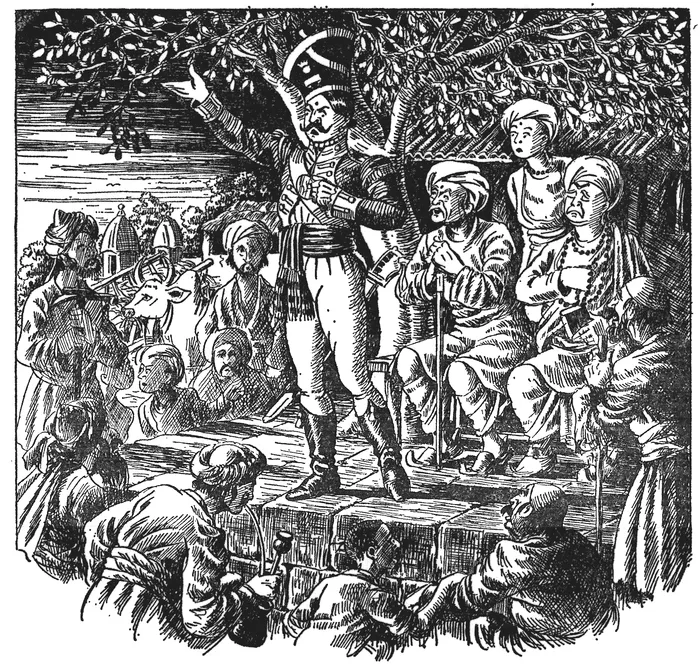

My mother had a brother, by name Hanuman, who was in the service of the Company Bahadur, and was a Jemadar in an infantry battalion. He had come home on leave for six months, and on his way to his own home, he stayed with my father. My uncle was a very handsome man, and of great personal strength. He used of an evening to sit on the seat before our house, and relate the wonders of the world he had seen, and the prosperity of the great Company Bahadur he served, to a crowd of eager listeners, who with open mouths and staring eyes took in all his marvels as undoubted truths. None of his hearers were more attentive than myself, and from these recitals I imbibed a strong desire to enter the world, and try the fortune of a soldier.

Nothing else could I think of, day or night. The rank of Jemadar I looked on as quite equal to that of Ghazidin Hydar, the King of Oudh himself; in fact, never having seen the latter, I naturally considered my uncle as of even more importance. He had such a splendid necklace of gold beads, and a curious bright red coat, covered with gold buttons; and, above all, he appeared to have an unlimited supply of gold mohurs.2 I longed for the time when I might possess the same, which I then thought would be directly I became the Company Bahadur's servant.

My uncle had observed how attentive I was to all his stories, and how military ardour had inflamed my breast, and certainly he did all in his power to encourage me. He never said anything about it before my father and mother, or the priest; still, he repeatedly told me privately that if I wished to be a soldier, he would take me back with him on his return to the regiment. How I longed to mention this to my mother, but dared not for I well knew her dearest wish was for me to become a priest. However, one day when I had been reading with Duleep Ram about the mighty battles fought by the gods, I fairly told him my wish to become a soldier. How horrified he seemed! How he reproached me, declaring that all the instruction he had so laboured to impart to me was thrown away, and that half the stories my uncle had told me were false; that I might be flogged, and certainly should be defiled by entering the Company's service. A hundred other terrors he conjured up, but these had no effect on me.

The priest immediately went to my parents and informed them of my determination, and thus broke to them the subject I had not the courage to tell. To my great surprise my father made no objections; these all came from my mother, who wept, scolded, entreated, and threatened me, ending by imploring me to give up the idea, and abused my father for not preventing such a catastrophe. At this particular period of which I now write a lawsuit was impending over my father, about his right to a mango grove of some 400 trees, and he thought that having a son in the Company Bahadur's service would be the means of getting his case attended to in the law courts of Lucknow; for it was well known that a petition sent by a soldier, through his commanding officer, who forwarded it on to the Resident sahib3 in Lucknow, generally had prompt attention paid to it, and carried more weight than even the bribes and party interest of a mere subject of the King of Oudh.

Shortly after my parents had been informed of my desire to take service with Company Bahadur my uncle left them to proceed to his own home fifty miles away. Although my mother never expressed any wish for him to pay another visit when he was about to return to his regiment on the expiration of his leave, he told her that he intended to do so, and that he should take me with him if I were still of the same mind. I walked the first few miles with him on his journey, and made him tell me all about the service I wished to enter, over and over again.

Upon my return home I had to sustain the united attacks of the priest and my mother. They tried every inducement to make me give up the idea. My mother even cursed the day her brother had set foot in our house, but all they could get from me was a promise that I would think over the matter. This I did, and every day became more and more determined to follow my uncle. I now felt idle, and did very little else than learn to wrestle or play with sword-sticks, and consequently neglected my father's fields, which caused me to fall under his displeasure. However a threat from him that I should never be allowed to see my uncle again had the effect of bringing me a little to my senses, and my father had no occasion to find fault with me afterwards.

The months passed away, and the rainy season had ended. I was engaged in cutting sugar-cane, with my back towards the road, when I was called by name by someone on a pony. I soon recognized my uncle and flew to his embrace. After inquiries for my father and mother, he asked me if I wished to be a soldier still, and looked pleased when I answered so decidedly, 'Yes'. He told me I was a fine young fellow and that I should go with him.

My uncle remained a few days at our house, during which time, having my father to back him up, he in a measure succeeded in bringing my mother to think it was my destiny to be a soldier, and her fate to part with her son. The priest was requested to look at my horoscope and discover the lucky day for my departure, which he informed us, in the evening, would be at six o'clock in the morning of the fourth day from that day, if no thunder was heard during the period. How anxiously I watched the clouds during those days! How I prayed to the gods of the rain and clouds! And in the evening of the third day, when some dark clouds came up, I was in despair lest rain should fall, and fate be against me.

Duleep, the priest, who really loved me, gave me lots of advice, and made me promise never to disgrace my brahminical thread.4 He also gave me a charm in which was some dust a thousand Brahmins had trod at holy Allahabad, and he assured me that this charm was so powerful that as long as I kept it no harm could ever befall me. He bestowed on me likewise a book of our holy poems. My father bought me a pony, but gave me no money, as he considered I was now under my uncle's care, and that he could well support me.

The morning came unclouded. It was 10 October 1812,5 and at six o'clock in the morning I and my uncle left my home to enter what for me was an unknown world. Just before starting, my mother violently kissed me, and gave me six gold mohurs sewn in a cloth bag, but being convinced that it was her fate to part with me, she uttered no words but moaned piteously. My worldly baggage when I left home consisted of my pony, my bag of gold mohurs, a small brass bowl and string,6 three brass dishes, one iron dish and spoon, two changes of clothes, a smart turban, a small axe (for self-protection), and a pair of shoes. My uncle's baggage greatly exceeded mine; it was rolled up in a large bundle and carried by a coolie from village to village. This poor man considered himself amply rewarded for his day's work by our giving him whatever bread was left over after the daily meal.

'He bestowed on me likewise a book of our holy poems'

1 There were three grades of native officer. The junior was Jemadar, the next was Subedar, or Rissaldar in the Cavalry. The senior was Subedar- or Rissaldar-Major, of which there was only one in each infantry battalion or cavalry regiment.

2 Gold mohurs were part of the coinage of the Mughul Empire.

3 The East India Company was represented at the court of the King of Oudh by a Resident, who was a senior civil or military officer of the Company's service. His duties were supposedly advisory, but in fact the King knew that behind the advice lay the ultimate sanction of force.

4 This thread is worn next to the skin, hanging loosely across the body from the shoulder, and is never removed, not even for bathing. It is one of the distinguishing marks of an orthodox Brahmin.

5 Sita Ram is inclined to be hazy over dates, which is not surprising in view of his age when he was writing his memoirs, and the fact that the Christian calendar differs from the Hindu. He probably means 1814, not 1812, since he says he was seventeen years old when he set off to join the army.

6 None but a Brahmin can cook for a Brahmin, or draw water for a Brahmin. Hence the small brass bowl with a string to let down into a well to draw water.