eBook - ePub

The Congress in Tamilnad

Nationalist Politics in South India, 1919-1937

David Arnold

This is a test

Share book

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Congress in Tamilnad

Nationalist Politics in South India, 1919-1937

David Arnold

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Although primarily defined in cultural terms, as the land of the Tamil-speaking people, Tamilnad's geographical location in the south-eastern corner of the Indian sub-continent has enabled it to develop and maintain a distinctive character. The story of the Congress in Tamilnad has two essential themes. One is the evolution of the Tamil Congress as a regional political party. The second is the changing relationship between a nationalist movement and a colonial regime. Examining in close detail these themes, this book, first published in 1977, presents the story of the Congress in Tamilnad as a case-study of how nationalist parties evolved during the later stages of colonialism.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Congress in Tamilnad an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Congress in Tamilnad by David Arnold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du monde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

NATIONALIST AND REGIONAL POLITICS

The Tamil Country

Tamilnad has been described as “a country, almost a nation, on its own.”1 Although primarily defined in cultural terms, as the land of the Tamil-speaking people, Tamilnad’s geographical location in the south-eastern corner of the Indian sub-continent has enabled it to develop and maintain a distinctive cultural character. To the east lies the Bay of Bengal; to the west and north-west an upland rim divides the Tamil country from Kerala and the Deccan. Within the region’s 50,000 square miles diversity is muted, and there is a gradual transition from the low-lying Coromandel coast to the dry interior plateaux. One impression prevails: an arid region of scattered palms and outcrops of grey and tawny rock, relieved by the occasional flash of vivid green rice fields and the glimpse of an ornate temple pagoda.

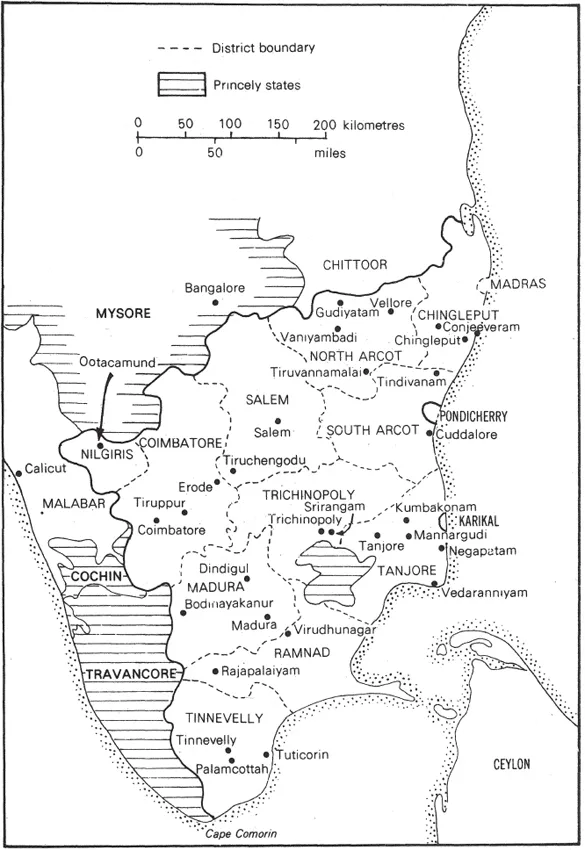

For a century and a half – from the end of the eighteenth century until Indian independence in 1947 – Tamilnad was part of the Madras Presidency. A sprawling, polyglot province, Madras incorporated Malabar and South Canara on the west coast and parts of the Telugu, Kannada and Oriya linguistic regions to the north. But the Tamil districts were the dominant element in the presidency: they constituted a third of the land area and half the population – 21 million out of nearly 43 million in 1921. Tamilnad was more urban than its regional neighbours: there were 175 officially classified cities and towns in the Tamil region in 1921 compared to 111 in the Telugu districts and nine in Malabar; 15.5 per cent of Tamils lived in urban areas compared to 10.6 of Telugus and 7.2 of Malayalis.2 By 1931 nine of the 15 largest towns and cities in the presidency were located in Tamilnad, including the four most populous – Madras (647,230), Madura (182,018), Trichinopoly (142,843), and Salem (102,179). Calicut, Malabar’s expanding port, was the nearest rival, with a population of 99,273 in 1931; the Telugus’ Cocanada lagged far behind with 65,952.3 Tamilnad was further distinguished from its neighbours, in that, unlike the other linguistic regions of the Dravidian south, almost the whole of the Tamil-speaking area was under one administration. Kerala was partitioned between the princely states of Travancore and Cochin and the Malabar district of the Madras Presidency; Andhra was split between British Madras and princely Hyderabad; Karnataka was torn between Madras, Bombay and Mysore state. By contrast, only the small Tamil population in the French enclaves of Pondicherry and Karikal on the east coast, in the state of Pudukkottai, and in southern Travancore lay outside the presidency. Thus, the Tamil districts of the province constituted a relatively compact and homogeneous linguistic block, and they correspond closely to the state of Madras (renamed Tamilnad or Tamil Nadu in 1969) which was formed by the reorganization of India’s states on linguistic lines in 1956.

Distinctive though the Tamil region was, it nonetheless remained throughout the colonial period an integral part of the British province of Madras. From 1920 Tamil Congressmen had their own “Provincial” Congress Committee, but they could not ignore political developments which affected the presidency as a whole. In particular, Tamilnad’s Congressmen in the provincial Legislative Council had to work alongside partymen and allies from the other linguistic regions of the presidency. This was a frequent source of friction, most noticeably between Tamil and Telugu Congressmen.

Despite Telugu claims to the contrary Madras was predominantly a Tamil city. In British hands since 1639, it had grown far less rapidly than Calcutta and Bombay. A more modest, more leisurely city, it was akin to an English county town only marginally influenced by the industrial revolution, rather than to a London, Manchester or Sheffield. Since the 1870s, the decade in which the harbour was built and the first cotton mill established, Madras had developed as a commercial and industrial centre, but in the 1920s much of the city still had a semi-rural appearance and only in the north-west, around the railway workshops and textile mills, did Madras show the grim face of early industrialization.

No other city in Tamilnad was as large or as varied as Madras, but, unlike Calcutta, it was not an urban colossus which dwarfed every other town in the presidency. Tamilnad could boast of more than half-a-dozen substantial towns, most of which had been administrative, religious, educational and commercial centres under pre-British regimes and which had survived as district or taluk headquarters under the new rulers. Madura and Trichinopoly in particular were the rivals of Madras, and during the 1920s and 1930s their rivalry found expression in the contest between Congress factions in the presidency town and the mofussil (up-country districts).

Map 2. The Tamil country.

The great majority of Tamils lived not in the towns and cities, but on the land. The basis of economic activity in the region was overwhelmingly agricultural, with rural population densities greatest in the irrigated river valleys, especially the delta of the Cauvery. The presidency as a whole had an average density of 329 people per square mile in 1931, but in Tanjore, the district which covered most of the Cauvery delta, the average density was over 600, and in other eastern districts with extensive river irrigation the figure rose above 400 in many taluks.4 Rice was the principal crop grown on these “wet” lands: in 1922-23, for example 47 per cent of the total cultivated area of Tanjore was under rice. 5 Intensive cultivation on this scale was only possible through river irrigation. Except for a narrow coastal strip, which received over 40 inches of rain a year, Tamilnad had to subsist on a rainfall of between 20 and 40 inches, concentrated mainly in the monsoon months. In the dry interior agriculture was assisted by tank and well irrigation: tobacco, sugar-cane, chillies, and long-staple cotton were grown. Elsewhere, on the unirrigated lands, cultivators produced millets (the principal food-grain of poorer Tamils), groundnuts, and oil-seeds. In the western districts of Tamilnad cattle were extensively used for drawing water from deep wells and ploughing the heavy soils: hides and skins were a major export item and the basis for tanning works in Erode and around Madras city. Direct European involvement in agricultural production was confined to the tea and coffee estates of the Nilgiri and Anaimalai hills.

Small landholders predominated in Tamilnad. Before the British period, land was seldom regarded as individual property and a marketable commodity, but as being under the collective control of the village community. In some areas, especially the rice lands of Tanjore, Trichinopoly and the north-east, there were leading villagers, known as mirasdars, with hereditary land rights, and these sometimes controlled agricultural production over hundreds, even thousands, of acres. Less extensive, but also involving hereditary rights, were lands held by inamdars. These were generally small plots of land given by local rulers as rewards for services: inamdars were most frequently Brahmins and were usually regarded as holding land for their religious institutions rather than as individuals.6 The British did not eliminate these pre-existing land rights, but over most of Tamilnad they promoted the individual ryot to become the landholder, responsible solely to the government for his land taxes.7 No more than a quarter of the land area of the Madras Presidency was under the zamindari system, by which large landed proprietors were established as intermediaries between the ryots and the government with rights of tax collection on their own estates. The zamindari tracts were to be found mainly in the northern Telugu districts, but there was a smaller belt of zamindaris in Tamilnad running from North Arcot and Salem to Madura and Tinnevelly. In each of these districts at the beginning of the twentieth century there were upwards of a million acres under zamindars.8

The ryotwari system undoubtedly moulded the region’s political and social character. The zamindars of Tamilnad, unlike their counterparts in Bengal, the United Provinces, or even Andhra, were too few in number and commanded too little influence in rural society to provide a solid prop for the British regime or to be valuable intermediaries between the colonial administration and the cultivators. It was the tax-paying ryots on whose tolerance, collaboration and self-interest the Madras government depended in Tamilnad. They were numerically important – a factor of increasing importance with the progressive expansion of the franchise in the twentieth century; they constituted a social stratum through which the British could hope to regulate rural life; and, from the late nineteenth century, the wealthy ryots were extending their range of economic activity as wealth derived from cash-crop production, marketing and money-lending was invested in western-education, enabling a new generation to enter urban professions and the bureaucracy.9 It was largely because of this diversification that non-Brahmins from rural agrarian and trading castes came into conflict with the Brahmins.

Politics and Social Conflict

The first steps towards nationalist agitation in Tamilnad were taken by the non-Brahmin merchants of Madras city. In the mid-nineteenth century the proselytizing activities of Christian missionaries, aided by government officials, aroused the religious indignation of the Hindu merchants. In 1842 Pachaiyappa’s College was founded in Madras under merchant patronage to provide an alternative to the educational institutions of the missionaries; and in 1844 G. Lakshmanarasu Chetti, a Telugu merchant, launched the Crescent newspaper to defend “the rights and privileges of the Hindu community.”10 The merchants had an additional grievance: they disliked the existing powers of the East India Company and, with the renewal of the Company’s charter in the offing, they sought to pressure Parliament to remove its unfavourable features. In response to suggestions from the British Indian Association in Calcutta, Madras merchants formed a local branch of the association in February 1852, replacing it six months later by an independent body, the Madras Native Association. It aimed to amend the Company charter, revise the taxation system, and curb missionary activity. The association was active for 10 years, but with the transfer of British India from the East India Company to the Crown in 1858, one of the main grievances of the association was removed and by July 1862 it had become “practically defunct”.11

The early political leadership of the Madras merchants did not continue. Being in the presidency town, with some knowledge of the English language, and close to the centre of provincial administration, the merchants were well placed to voice protests against the government. But the merchant community was, at this stage, heavily dependent on European-controlled trade and European business houses in the city. Compradors, lacking an independent economic base, they were not sufficiently independent and confident to mount a more serious and sustained challenge to the British. Further, the city merchants had neither a sufficiently attractive cause nor the organizational base to mobilize wider support for the Madras Native Association. A smaller commercial and industrial centre than Calcutta and Bombay, Madras lagged behind them in producing an Indian commercial middle class which could provide nationalist leadership.

It was, therefore, the professional middle class which took the lead in organizing an anti-colonial movement in Tamilnad. A region which could boast few merchant princes and even fewer captains of industry, Tamilnad was prolific in its output of graduates. By 1880 the region had 15 arts colleges and 50 high schools; Madras Presidency was producing as many graduates as Bengal, and the majority of them came from Tamilnad. Between 1858 and 1894 Madras University awarded arts degrees to 1,900 Tamil students as against 500 Malayalis, 450 Telugus, and 300 Kannarese. Among the Tamils, Brahmins predominated, most of them coming from landholding families in Tanjore, Tinnevelly, Chingleput and Trichinopoly. Non-Brahmins constituted only a fifth of the graduates and of these many were Nairs from the west coast. As yet high-ranking Tamil non-Brahmins saw little economic and social advantage in having degrees and becoming pen-pushers.12 There were historical reasons for this communal disparity. A smaller percentage of the Hindu population than in most Indian regions, the Brahmins of Tamilnad wielded economic and social power that was quite disproportionate to their numbers. In the presidency as a whole Brahmins constituted 3.3 per cent of Hindus. In Tamilnad their percentage of the total population ranged from one per cent in the Nilgiris to 3.7 in Tinnevelly and 6.9 in Tanjore, their area of greatest concentration.13 Ritual supremacy in Hindu society was only one of the bases of Brahmin power in Tamilnad, As the literati of the society they had long been clerks, administrators and officials whether the rulers were Tamil kings, Vijayanagar viceroys, or the East India Company. In the villages Brahmins almost invariably held the office of karnam or village accountant, and in appreciation of their religious and secular services they had been awarded land rights as mirasdars and inamdars. In the rice-growing eastern zones generally, and the Cauvery delta in particular, Brahmins were powerful not only by virtue of their priestly authority, but also for their prominence among the landholding classes. In western Tamilnad, where Brahmins held little land, they were frequently present as small-town money-lenders and bankers. The position of the Brahmins was exceptional in another respect: they were divorced from the process of agricultural production. Most non-Brahmin ryots were part-time or full-time cultivators, but Tamil Brahmins considered ploughing a ritually polluting act. However small their holdings, they would not till the land themselves. They were, therefore, entirely dependent on hired labourers, sub-tenants, and, until the British outlawed formal servitude, untouchable slaves. The Brahmins were free to devote themselves to religion and non-agrarian pursuits; they could easily become absentee landlords and pursue careers outside the village community. From the mid-nineteenth century Brahmins, particularly those from the Cauvery delta, invested their landed wealth in education, entered urban occupations and gradually sold their land to non-Brahmin ryots.14

Traditional status, access to landed wealth, generations of involvement in the administration, aloofness from cultivation: these factors were together responsible for Brahmin domination of the western-educated, professional middle class forming in Tamilnad from the middle of the nineteenth century. One indicator of Brahmin professional hegemony was literacy, especially in English, the key to bureaucratic and professional employment. The male vernacular literacy rate among Tamil Brahmins was recorded as 71.5 per cent in the 1921 census as against 59.7 for Telugu Brahmins and 24.2 for Vellalas, the leading non-Brahmin caste group in Tamilnad. But male literacy rates in English were even more striking: 28.2 for the Tamil Brahmins against 17.4 for the Telugu Brahmins and 2.4 for the Vellalas.15

The rapid expansion of higher education in the third quarter of the nineteenth century soon created a surplus of graduates. Government service in the presidency and in neighbouring princely states offered the main field for graduate employment, but by the 1870s and 1880s jobs in the bureaucracy were becoming scarce; the European monopoly of the higher echelons and Indian nepotism made entry for outsiders even harder. Exclusion from bureaucratic employment provoked the frustrated graduates to criticize selection procedures for government service and sharpened their complaints against officials’ conduct. Graduates sought other occupations: they turned to law, medicine, education, journalism and accountancy, but there, too, they ran headlong into conflict with European professionals. In some fields educated Indians had advantages over their European rivals. Brahmin lawyers, equipped with a knowledge of Sanskrit and traditional Hindu law which few Europeans could hope to match, won control of the original side of their profession in the 1880s and were beginning to oust Europeans from the appellate side as well.16

Thus the second phase of early nationalist agitation in Tamilnad in the 1880s was largely that of an emerging Brahmin professional middle class in conflict with European professionals. This conflict was expressed in various forms: one was sustained Brahmin criticism of European government servants; another was resentm...