Urban Planning's Philosophical Entanglements

The Rugged, Dialectical Path from Knowledge to Action

Richard S Bolan

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Urban Planning's Philosophical Entanglements

The Rugged, Dialectical Path from Knowledge to Action

Richard S Bolan

About This Book

Urban Planning's Philosophical Entanglements explores the long-held idea that urban planning is the link in moving from knowledge to action. Observing that the knowledge domain of the planning profession is constantly expanding, the approach is a deep philosophical analysis of what is the quality and character of understanding that urban planners need for expert engagement in urban planning episodes. This book philosophically analyses the problems in understanding the nature of action — both individual and social action. Included in the analysis are the philosophical concerns regarding space/place and the institution of private property. The final chapter extensively explores the linkage between knowledge and action. This emerges as the process of design in seeking better urban communities — design processes that go beyond buildings, tools, or fashions but are focused on bettering human urban relationships.

Urban Planning's Philosophical Entanglements provides rich analysis and understanding of the theory and history of planning and what it means for planning practitioners on the ground.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Part I

Knowledge and Expertise

2 The Knowledge–Action Problem

Rational Decision Theory

- Practical rationality pertains to the thought processes associated with the pursuit of pragmatic and egoistic interests. It is the means by which individuals take account of the world as it exists and calculate the most expedient means of dealing with it (this is the heart of rational choice theory, particularly in economics).

- Theoretical rationality is a process in which humans seek mastery over the world through the attribution of causality developed by increasingly precise abstract concepts (one example is physics: see Chapter 4).

- Substantive rationality is a form of rationalization that embodies not a purely means–ends calculation but rather the development of patterns of action based on value postulates or clusters of values. Substantive rationality is that reasoning through which values, in and of themselves, come to be accepted. Weber states:Something is not of itself ‘irrational,’ but rather becomes so when examined from a specific ‘rational’ standpoint. Every religious person is ‘irrational’ for every irreligious person, and every hedonist likewise views every ascetic way of life as ‘irrational,’ even if, measured in terms of its ultimate values, a ‘rationalization’ has taken place.(quoted in Kalberg, 1980, 1156)Thus, in Weber’s terms, differing lifestyles or life worlds defend their own values as “rational” and label others “irrational.” Weber also argues that there is, thus, no absolute standard for substantive rationality. The best contemporary case is found in political ideologies where progressive left ideology sees conservatism as irrational and conservative right ideology sees progressivism as irrational.

- Formal rationality relates to those thought processes that seek to codify practical rationality with reference to a substantively rationalized worldview of value. The result is formal laws, rules, regulations, and formally structured institutional patterns of domination and administration. This is discussed more fully in Chapter 5.

Outline of the Problem

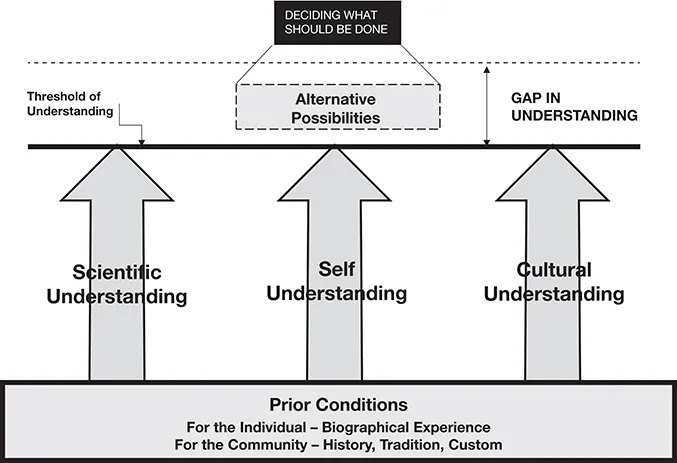

A. A Cartoon of the Knowledge–Action Problem