The ideological position of Athens: the importance of public architecture

The monumental projects made for the new capital of Greece after independence (1830) are explained by the position of nineteenth-century Athens in the Hellenic world and in Europe. From the ideological viewpoint, that position is absolutely prominent among all Greek cities. Athens has a particularity that differentiates considerably the context of its evolution from all other European capitals, with the exception of Rome. This particularity is the existence of its world-famous classical antiquities. Until the mid-eighteenth century, when all the routes of the Europeans’ grand tour were leading their footsteps to Rome, their acquaintance with antiquity was taking place through the Roman ‘filter’. However, after the publication of The Antiquities of Athens by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett in 1762, the first to have systematically studied them, the Greek antiquities became widely known and attracted the interest of European antiquity lovers, representing for them the embodiment of the classical world. That coincided with the publishing in 1764 of the German art historian’s Johann J. Winckelmann major work, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (‘History of Ancient Art’), which played a decisive role in their progressive reevaluation and in the reconsideration of their position vis-à-vis Rome, regarded until then as the summit of ancient culture. For European art lovers, the reasons for the existence of Athens were the natural presence of ancient ruins, the ancient names, and the memories evoked by them (Klenze, 1838, pp. 20, 420; Maurer, 1943–1947, pp. 119–127; Hederer, 1976, p. 199).1 Naturally, the way in which Western Europeans saw Athens was one of the main reasons it was chosen as the capital of the new Greek state (Klenze, 1838, p. 397; Papageorgiou-Venetas, 1994; Bastea, 2000, pp. 6–11; Fatsea, 2000).

Furthermore, the newly appointed King of Greece was Otto (1833–1862), the underage2 son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Ludwig was perhaps the greatest antiquity lover among all European monarchs, as his building programme in Munich and his collections of art suggest. The choice of Otto for the Greek throne by the Great Powers thus led to the particularly intense influence of German classicism in Greece. That reinforced the ideological context of the new capital’s inception.

The transfer of the capital from Nafplion to Athens was largely due to the desire of the authorities to offer the new kingdom an ideological unity, which was lacking after so many centuries in the multinational Ottoman Empire. The sought-after ideological unity would satisfy the two main axes set at the state’s inception: its reconnection with its ancient past and its entry in the family of the civilised nations of Western Europe. That unity would differentiate Greece from the East and approach her to Europe. Therefore, Greece had to erase every trace of her Eastern character and retransform on the basis of her ancient heritage. The most appropriate town for the fulfilment of that purpose was Athens, where the ancient past was present more than anywhere else. Thus, Athens was preferred to other more suitable alternatives, although it had the least geographical and financial qualifications to assume that role. Moreover, among several alternative solutions about the exact siting of the new city, the final choice was exactly the one connecting it in space most firmly with its ancient predecessor, against all practical considerations.

The new capital had to replace every Eastern characteristic with the ‘Occidental’ image that would express the authority of its European monarch and would incarnate the name of ‘Athens’, as the Western European antiquity lovers understood it. The plan of the new city would be a modern ‘answer’ to the medieval urban fabric, which was the outcome of a free, ‘organic’ development.

Especially under King Otto, the superficial Europeanization (through architecture, clothing, spectacles, etc.) preceded by a long way the respective adjustment of socio-economic structures, which, of course, needed much more time. The task of filling that gap won’t be fulfilled before the end of the century, in the last years of King George I’s reign (1863–1913; son of King Christian IX of Denmark). It must be underlined that all projects serving that purpose were prepared or inspired by Western Europeans or by Greeks who had spent a great part of their lives in Western Europe and were fervent supporters of that view.

Public architecture would be essential to the fulfilment of that purpose. Since the newly founded Greek state hadn’t the necessary conditions of a financial development, it would have to acquire its sought-after European character through its institutions. Those were based on the institutions of the European countries that constituted the models for nineteenth-century Greece, and the most suitable representatives of those European institutions would be the buildings that would house them. This accounts for the particular importance of public architecture in Athens.

However, contrary to other European capitals, in Athens the interest centred not on administrative edifices, but on buildings housing cultural institutions, especially educational. Greece lacked appropriate buildings to house the new institutions, as well as educated people who would build those buildings and staff those institutions. The revolution had caused the destruction of the new kingdom’s towns and villages. Thus, schools, university, schools of engineering, and architecture were urgently needed, just as hospitals and so forth. The new authorities had to find premises, mostly existing buildings that were rapidly restored, but more importantly, they had to seek or train literate people to get the economy and the society to move on. But, in addition to that, reborn Greece was supposed to undertake the cultural renaissance of her whole historic area – mostly included in the Ottoman Empire – and the revival of her ancient glory in the cultural domain. That was very eloquently expressed by Lysandros Kaftantzoglou, the most famous Greek architect of the nineteenth century, in his speech on the occasion of the Polytechnic’s anniversary, and again much later by Dimitrios Bikelas, future first president of the International Olympic Committee, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the University of Athens (the occasions are particularly significant; Kaftantzoglou, 1847, p. 9; Πανδώρα, 1855, p. 555; Bikelas, 1888, p. 78; Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, 1970–1978, vol. 13, p. 64). Therefore, educational buildings were given more attention than administrative constructions. Moreover, they should be as monumental as possible, in order to better express that desire and underline their symbolism.

However, others – especially the press – thought that Greece should avoid spending money on the construction of unnecessarily monumental buildings of symbolical value and focus on covering urgent practical needs, which were innumerable. From that point on, the ideological way of seeing Athens would be in a perpetual antagonism with its practical needs.

The first intention to satisfy the needs of the future new European state was expressed by the Demogerontia3 of Athens in 1822, when the city was temporarily liberated (Kabouroglous, 1922, pp. 401–402), but the effort was interrupted by its recapture in 1827. Thus, the application of those projects began under Ioannis Capodistria, first governor of liberated Greece, before the arrival of King Otto. That time’s choices demonstrate Capodistria’s practical spirit, an outcome of his experience as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Empire in 1815–1821. The governor believed that the urgent needs were the construction of hospitals and the education of the major victims of the War of Independence (namely, children and especially orphans); the protection of the major asset of the Greek nation, the antiquities, which played a decisive role in the appearance of the philhellenic movement and therefore in the liberation of Greece; and finally the state’s organisation. Thus, the first public edifice constructed in Aegina, first capital of Greece, in 1828, was the Orphanage (Ross, 1863, p. 26). Although simple, it was then characterised as a ‘splendid structure’ and housed also the Central School, the Museum, the Library, and the Printing House. In those first years of independence, priority is given to schools, while some administrative buildings were also erected in other cities.

Nevertheless, Capodistria’s views were very far from the ideology not only of the Bavarian dynasty that succeeded him, but also of the scholars and benefactors, whose role in the new state was decisive. That was firstly demonstrated by the capital’s master plans.

The first master plans: intentions and final development

The special position of Athens in the Hellenic world accounts for the intense idealism characterising every project during the first decades after independence. That idealism ignored the material realities of the country, for it counted on a very imminent expansion toward all territories inhabited by Greeks and a consequent spectacular change of circumstances. Thus, the same idealism is reflected in the first propositions made for the new capital’s city plan. Only after the events related to the Crimean War, in 1854, the Greeks, disillusioned in regard to the role of the Western European powers, started accepting that the expansion of the Greek state and the creation of a big country wasn’t for the immediate future. That had at least one positive outcome: the Greek authorities concentrated their efforts not in obtaining more resources for Greece by expansion, but in enhancing whatever resources Greece already had. That resulted in some serious efforts to create infrastructures.

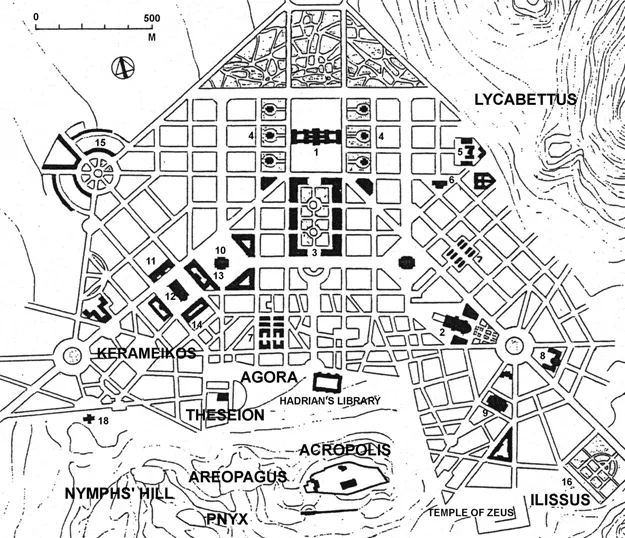

The first official plan made in 1833 (Figure 1.1) was commissioned by the Greek government from the Greek architect Stamatios Kleanthes and his German colleague Eduard Schaubert, pupils of Carl Friedrich von Schinkel. In this plan, the Royal Palace is situated at the top of a triangle, like the Palace of Versailles. From the palace’s square three streets depart radially: Piraeus, Athena, and Stadium. Stadium Street, the triangle’s right side, connects the palace to the ancient stadium, while Piraeus Street, the left side, ensures the connection with Athens’s homonymous ancient port.

Athena Street is the triangle’s bisector. It links visually the Royal Palace to the Acropolis, with the interference of the market, which, as its position and size suggest, was destined to become the modern city’s centre. At the same time, it is the new city’s main street. Along with two narrower parallel streets, Aeolus and Areopagus, it would link it to the old one, through its penetration into the latter. Also Hermes Street, the triangle’s base, would penetrate the old urban fabric.

Figure 1.1 Plan of Stamatios Kleanthes and Eduard Schaubert for the new city of Athens

Re-drawn by the author, using several versions of the plan, with the addition of location names: 1. Royal Palace; 2. Cathedral; 3. Central Market; 4. Ministries; 5. Garrison; 6. Mint; 7. Market; 8. Academy; 9. Library; 10. Stock Exchange; 11. Parliament; 12. Church; 13. Post Office; 14. Headquarters; 15. Oil Press; 16. Botanical Garden; 17. Exhibition Hall; 18. Observatory.

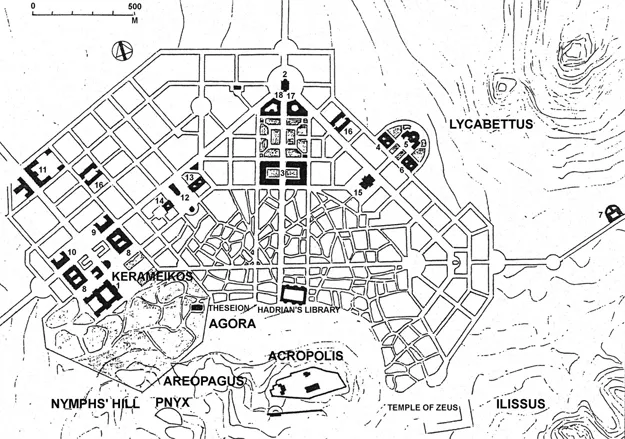

However, the realisation of the Kleanthes and Schaubert project would be too costly, because of the expropriations it would entail for the creation of wide avenues and extended gardens and squares on private land. Consequently, in 1834 the Bavarian architect Leo von Klenze, official architect to King Ludwig I of Bavaria, undertook to adapt it to Greek realities (Figure 1.2). Von Klenze maintained the urban triangle. The role of Athena Street as the main link between the new European capital and the old Ottoman town remained untouched and was even accentuated, since only one of the two other streets penetrating into the old urban fabric – Aeolus Street – was maintained, considerably diminished in width.

Figure 1.2 Modification of Kleanthes and Schaubert plan by Leo von Klenze

Re-drawn by the author, using several versions of the pla...