![]()

1

Revolutionary Ancestors of the Gamin de Paris

The nineteenth-century deployment of a boy as revolutionary agent and emblem traces its roots back to the Great Revolution of 1789, and to subsequent visual culture surrounding the child hero-martyrs Bara and Viala in imagery that is here briefly reviewed. Even as early as the spring of 1750, connections had been made between children and insurrection during the so-called Children’s Riots, although not in the same way as later. In this instance, the people of Paris directed their violence against the police, accusing them of kidnapping children for possible transport to the colonies. In the ensuing rumor and chaos, there was a blurring of distinctions between bourgeois, working-class, delinquent, and vagrant boys, including ubiquitous street urchins.1 Just over a decade later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile Or Treatise on Education (1762), which would have such an indelible effect on the French Revolution, set up a tension between nurturing the free expression of the natural boy’s individuality and applying the behavioral engineering of the tutor.2 Such questions would be further plumbed in terms of “civilization” and “primitivism” in Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard’s remarkable account of the original enfant sauvage in his The Wild Boy of Aveyron (1801).3 Both before and after Rousseau, French painters including Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson produced emblematic visual meditations on the education of the bourgeois boy, whose often-solitary, absorptive moods ranged from intense concentration to lyrical contemplation.4 These quiet boys in interior settings are not rowdy street urchins.

The Great Revolution, like its subsequent iterations in the nineteenth century, would attempt to find an interface between ideals of the educated boy and the street boy as emblem of “the people.” On the one hand, the Convention voted a decree establishing state primary schools, even as children read revolutionary manuals and catechisms to teach them about republican virtues.5 On the other hand, boys took oaths and marched in the streets in revolutionary guard battalions and festivals.6 This was an activity in which François Rude participated in 1792, as a working-class boy in Dijon, perhaps transmuting the memory of it in the later inclusion of a marching, ephebic gamin in his monumental sculpture La Marseillaise on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris (Figure 4.6). It is significant that when boy battalions took their oaths in ceremonies as enfants de la patrie, their fathers (including Rude’s) yielded them to “the fatherland” as part of the revolutionary rhetoric of the family in the social imaginary.7

Paternal authority, in fact, increasingly came under pressure because of its inevitable links to the king as father figure, even as the cult of the child emerged in the aura of the father’s diminishing patriarchal role.8 The Republic became parent, taking over caring for its abandoned children and declaring the rights of illegitimate ones.9 Meanwhile, maternal imagery increasingly dominated the social imaginary in the wake of the Great Revolution, with la patrie blurring into and becoming effaced by la matrie (or la mère patrie) as homeland.10 Small boys in these images were often nursed, in a manner that would have pleased Rousseau, at the allegorical and fetishized breasts of the polyvalent figure of Marianne/Liberté/La République.11 These enfants de la patrie, united in a sensate bodily experience, thereby acquired connotations of “fraternity,” a component of the social imaginary that increasingly replaced the model of paternalism.12 This kind of destabilization of the traditional patriarchal family model would continue in the nineteenth century.13 The explicit or implicit erotics of the relationship between male children and the maternal figure of Liberty would likewise continue in the visual imaginary, including Delacroix’s painting. The multiracial revolutionary fraternity of black and white boys depicted nursing at the breast of la patrie, with the black boy alluding to the struggle against slavery in French colonies,14 would have a transformed, and, in many respects, reversed, afterlife in later illustrations for colonialist novels about the gamin de Paris.

Predecessors for the gamin de Paris during the Great Revolution could also be found in scenes of boys marching like soldiers, playing at being republican men,15 as well as in the margins of visual representations of revolutionary activities of “the people,” or sometimes more centrally in depictions of revolutionary drummer boys in the thick of battle, notably the Napoleonic battle at Arcole.16 The drum became a frequent attribute of the most famous of the child hero-martyrs of the Great Revolution, Joseph Barra, even though he in all probability never played or carried one.

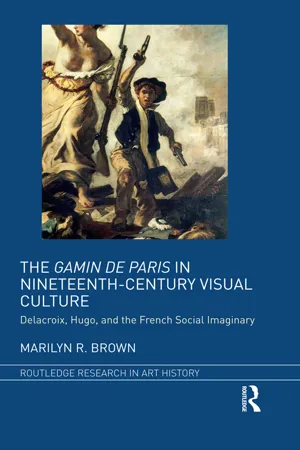

Like the legend of the boy hero Agricol Viala, the myth of Barra’s supposed martyrdom for the Revolution was fabricated for propagandistic purposes.17 It was especially convenient that neither boy had a father, thereby emphasizing their roles as enfants de la patrie and enfants du peuple. Held up as virtuous examples to the nation, Bara and Viala were depicted in popular prints being crowned by female figures of Liberty, providing a prototype for the close juxtaposition of Liberty and the gamin de Paris on the right in Delacroix’s later picture.18 In the most famous revolutionary image of a child, Jacques-Louis David’s painting of the Death of Joseph Bara (Figure I.1), an androgynous innocence is maintained even as the ephebic nude boy, whose genitals are conveniently hidden, is presented as a violated martyr clutching to his breast the revolutionary cocarde (cockade).19 Bara here became a pubescent symbol of the state of childlike purity to which the Revolution aspired (but could not attain) during the Terror. In this invention of an unlikely Jacobin hero, David’s modification of the adult Academic male body, including the revolutionary symbol of Hercules, displaced child sexuality to an implicit level of the political unconscious.20 As we shall see, the visual example of Bara, if not the David, would be perpetuated in the nineteenth century in works by, among others, David d’Angers and Jean-Joseph Weerts (Plate 16), as well as in school manuals of the early Third Republic.21 Collective memory images of revolutionary boys would jostle and inflect those of the later gamins de Paris in the continuing trans formation of such notions as “fraternity,” “nation,” and “people” in the French social imaginary.

Notes