![]()

Chapter 1

The Challenges of Circumscribing the Other

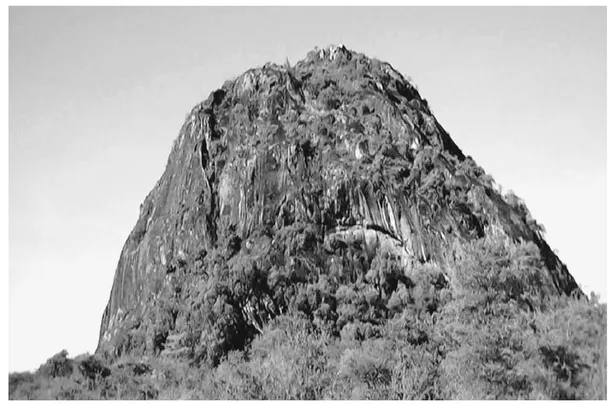

Sitting under a tree with barely enough shade from the dry-season sun, a small group of older men were talking with me outside their traditional homesteads. The discussion turned to ngipian (singular, ekipye), generally translated as spirits, although lightning is a particular form that they or their occurrence take. 'Ekipye can arrest someone at the dam' and the only way out of being stuck there at the dam is to sacrifice. Looking to the north, where hills of rock jutted out of the plain, one was selected for attention by a man only eight years older than myself. 'If you climb Lobel Hill, there is no return without sacrifice' (J31). Gesturing to the north at the volcanic plug, he gave a serious warning. "Because of ekipye, if you point your spear or gun at Lobel, you are pulled.' It was explained that this irreverent action to the spirit of that huge blancmange-shaped lump of rock would, of necessity, result in the offender being drawn to the hill to meet his fate. It was no joking matter, and no jokes were attempted. The efficacy of cause and consequence was not in the least disputed. It was simply the way things are. Nor are the effects limited to Karamojong.

Referring to the westernmost volcanic plug in Karamoja, Rwot at Alerek, Lokori Komol Namuya related how some British landed on top with a helicopter in the 1980s. They fell sick and died for their temerity, it was remembered, corroborating the habitual experience of the locals. The Karamojong cannot even make a corral near this rock, for the corral will be opened mysteriously in the night. The bare rock has its own spritely domestic beasts, and lost livestock may be translated there to this spirit-order of creation. The mysterious properties of the rock are not regularly tested by the Karamojong, for none of these physically brave people dare to scale it for fear of being 'beaten or taken up' by the spirit (J31). After all look what happened to the British, whose technological bravura did not save them! Whatever else may be happening around the world, Karamoja remains a place of enchantment, however uncongenial a fact that may be for modern missionary or postmodern scholar.

1 Tradition and Imagination

Traditions do exist in Africa as elsewhere. Despite the colonial experiment, or new attractions and conditions, there are always some that persist almost to the point of perversity. Further, new traditions are constructed through the collective choices of the people involved, even when the originating event has not been replicated.

Source: Ben Knighton

Photograph 1.1 Lobel volcanic plug, Najie

Tradition has to be owned and valued, if only in nostalgia. It is difficult to impose tradition. Traditions are held dear when people feel they have participated in initiating, maintaining, modulating or reforming them. Some traditions may be élitist, but then they are the traditions of the élite; the customs belong to them. If the masses voluntarily participate, then perhaps they own the élite! The most peculiar feature can be appropriated for a tradition and events intended only to be one-off can be instituted as a regular part of a calendar.

Traditions therefore emerge or die primarily through collective choice, which is why examining them frequently reveals significant features about the people who maintain them. Thus the term, 'traditional', has valuable import, and is more pertinent than 'indigenous', which relates to a place and puts the stress on origin. 'Traditional' also has a distinguished academic pedigree, being used by Max Weber (Mills, Gerth and Weber 1991) to describe one of three pure types of social activity: rational, traditional and charismatic, although these are attacked as essentialist. For Weber traditional leadership venerates the past and values loyalty and solidarity, characteristic of conservative societies that resist change. The danger when applying this typology to African societies, which Weber never studied, is that the observer is led into mistakenly thinking that traditional societies are necessarily changeless. Just how conservative and how much social change happens will be a special focus of this book, with no presumption that the Karamojong will be an example of the pure type.

Nowadays some courage is needed to depict a traditional African religion.1 Can it fit the terms of postmodern philosophy? If not, is it the account of the religion or the philosophy that needs to be revised? To update Evans-Pritchard (1965:15), some explanation of the absurdity seems to be required, for instance of the modern gun being thought to be subject to the compelling power of what appears as an old-fashioned nature-spirit. Reviving the use of 'traditional' after the Invention of Tradition (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1984) has exposed it carries three dangers. Firstly it risks participating in another round of the Eurocentric invention of Africa (Mudimbe 1988; 1995). Secondly not only has African tradition itself recently been seen to be part of what colonial rulers and their hireling anthropologists imagined for 'their' peoples, but also the concept of 'traditional' is being challenged by that of 'indigenous'.2 Thirdly the nature of religion is contested at least as much as ever (Eck 2000), and whether it is possible to talk of a discrete religion in regard to African ways of life is a further issue.

The concept of Africa, even when it was the 'unknown continent', was undoubtedly a European concept, but those who inhabit it want to contest the identity that has been imposed upon them, or sometimes to select from the various types that are on offer. From the romantic to the derogatory, from the cosmopolitan to the racist, Africas have been invented and are being imagined by many. Yet a portrait of all of Africa is not being painted here. The aim is to understand and articulate one small corner of a vast and varied continent without grandiose claims that this speaks for the rest. Neither is the opposite Adullamite reaction present, that this small corner is isolated from Africa and the rest of the world so needs no setting in wider movements. Yet it will not be claimed that the Karamojong are typical in their response to world trends such as globalization, nor even that they are typical of 'traditional' Africa, for even here, their commonalities tend to be with nomadic pastoralist peoples of Africa,3 not with an essence that defines the continent. It is their ability to resist easy categorization in more general theory that makes them such a fascinating subject for study. Thus, they are not being used as an exemplar of some fashionable line of funded inquiry, but are being depicted for who they are in their own right, so bringing to bear academic insight in the service of their truest representation (Knighton forthcoming).

It must be acknowledged that all representations run short of the complexity of reality, and that what, at best, can be laid between the two covers of a book will be an interpretation, and one that will modify others and then find a reaction in others to come. As an historian of religion Mircea Eliade (1959b:91) thought that he acted 'as a hermeneutist'. A long process of wrestling with contradictory interpretations and aggregation is necessary, drawing on multiple sources and the work of others, where that has been carefully done. Both function and meaning must emerge (Clarke 1988:822). How is the interpretation to be justified? Perhaps, as the late John V. Taylor (1963) found 'the Primal Vision' in his sympathetic study of the Baganda, it is because the vision of the Karamojong way of life is disclosed now at length. There is no intention here to employ Taylor's category of 'primal religion', but rather to show, remorselessly, not romantically, and not idealistically, the factors at work in the enduring vitality of a traditional religion.

2 Invention versus Appropriation

There are two major trends still in fashion today in African studies, yet they must clash before long. On the one hand there is the emphasis on the invention of tradition in Africa (Ranger 1983; 1993a; 1993b; 1998). Colonial rule created maps, defined ethnic groups when they realized the errors in the hastily drawn state boundaries, and manufactured a typology of tribes which even exchanged the ethnic identity of the colonized. The official codification of customary law could certainly be motivated by the desire of colonial governments to find convenient methods of social control (Lonsdale 1992a:209; Maxwell 1999:37). In any case the mores of a twentieth-century representation of the nineteenth century, frequently seen as timeless, could hardly reconstruct the past as it was, but conveniently gloss it. On the other hand, there is the great emphasis on the appropriation by Africans of whatever the invading white man had to bring: his religion, his politics, his education. Ranger (1995:248) finds, in Zimbabwe, that 'religious ideas offered a particular effective way for rural Africans to act upon their world'. Women are likewise seen to be subverting the strategies of men. In fact, those to whom power is attributed should better be seen as fellow-actors in the complex games that relate various interest groups, who compete and ally according to a multitude of factors, as has been found in the history of Buganda.

The social forces that combined and conflicted to shape Africa's history before the colonial period continued to be formative under European rule. More than that, the answer lies in seeing the colonial state as a part of African life right from the outset. Colonial administration did not write the history of their choosing: the colonial state did not develop in a manner determined by local officials, a metropole. or the world economy. On the contrary, it emerged in a contingent manner. Its officials (who, of course, were divided among themselves) were subject to the same conflicts and contradictions to which the people they ruled were subject. Africa's colonial history was driven by forces rooted in the precolonial era, but were refashioned as colonial officials reacted to circumstances they encountered and introduced and as different groups of Africans did the same. (McKnight 2000:84f)

These two trends of thought, invention and appropriation, pose a contradiction. If colonial rulers were so compromised, almost impotent to direct change over against African appropriation, if colonial history is so predicated by precolonial history, how could they invent anything sustainable? If there are traditions, whether old or new, from internal sources or appropriations, it must be anonymous Africans who founded them. Alternatively, if modernization inserted Africa into the world economy, breaking down tribal discipline and authority, how could any traditions persist at all, whether invented by Europeans or imagined by Africans?

The ambiguity is heightened by the use of the term 'African agency' (Lonsdale 2000a). What is meant to be emphasized by its usage is African activity and initiative, but the most common use of 'agent' and 'agency' in English is in legal, political and economic aspects where it always refers to activity for and accountable to another, the principal. Hence there used to be a chasm of subservience between, say, the missionary and the mission-agent the former might employ (Newman 2001). The formal relationship does not prevent the mission-agent from appropriating the dominant narrative to other ends, as Keswick Holiness spirituality was appropriated as an anti-clerical fellowship by the East African Revival. Yet the researcher has to be alive to the possibility that African agency may according to collective choice adopt, to a surprising and apparently dysfunctional extent, the religious ideas and practices of others. There are likely to be conditioning factors, perhaps pressure, even persecution, to convert, but it is in the field of religious ideas that human freedom is at its highest. Thus the African response needs to be carefully observed as to the extent to which Africans adopt, adapt or reject alternative religious traits.

3 Implicitness

The complexity of life on earth cannot be presented in one undifferentiated lump, so selection of the mass of phenomena will firstly be determined on the basis of pertinence to the more religious issues. Again, in the attempt to yield consonance with the alien, it is important that explanatory accounts will employ concepts not simply belonging to one academic discipline or another, 'but will reflect as well the concepts of the agents he studies' (Clarke and Byrne 1993:45). Many of the factors germane to the description of African religion are transcendental4 or implicit in the academic traditions involved, rather than explicit. Similarly, the implicit inevitably plays a vital rôle in religion.

In traditional African religion it is conceivable that the implicit has wider importance, because of the emphasis on ritual, custom and behaviour rather than on mythology, doctrine and belief, though it would be a mistake to suppose that a mental or intellectual side is lacking. There is undoubtedly a difference between oral and written ways of maintaining and multiplying knowledge, and oral memory skills are likely to be better honed than literate ones (Goody 1987:290). 'The implicit is the foundation of social intercourse' (Douglas 1975:5). Implicit knowledge here is taken, following Fardon's scheme (1990:5), to include tacit knowledge,5 assumed in a certain paradigm, and doxic knowledge, those cultural frames beyond proof or disproof that shape the self-evident experience of the world. It may be 'under your nose', so too obvious to state normally, but forms the presuppositions on which situated communication regularly takes place, or 'couldn't be otherwise' as a direct reflex of the way things incomprehensibly are. With all human life, not least in regard to technology in the West, there is a disparity between people's capacity to get on with life and their ability to articulate what is happening or why. Furthermore the unconscious and unreflective should not just be predicated on African peoples.

The implicit nature of traditional African religion is one feature that has avoided any direct attack by contemporary scholars. Wendy James (1988:4) writes of 'an archive, below the level of the explicit statements', and of the 'fundamental levels of silent knowledge' in Uduk divination.

You cannot so easily accept or reject the advocacy of the ebony oracle because in itself it stands for no dogma. In silence, it is attuned to the implicit assumptions of the proper balance within a person. It reveals the workings of the vulnerable inner person, relations between people, relations between the living and the dead, relations between people and the world of the wild. These matters [are] elusive, 'open-textured', and adaptable. (James 1988:6)6

The elusive quality of the significance of religious practices results in the religious aspect not being addressed first by researchers, except in a superficial way. Initial fieldwork is unlikely to accumulate sufficient material to nail the elusive and penetrate the implicit. James might respond here that it is only the elusive which is t...