![]()

1

God and the ‘Family of Princes’ Presided Over by the Byzantine Emperor

André Grabar

A long tradition, extending back to the origins of the Christian Empire and even further, led the Byzantines of the Middle Ages to conceive of their foreign policy on two different levels: that of reality and that of historiosophical doctrine. Thus a campaign against the Goths or the Bulgars, the Russians or the Serbs would be invested, under the pen of a Byzantine, with the consecrated character of the irreconcilable struggle between the Empire and the barbarian world. Likewise, in times of peace, the material reality of the relations between Byzantium and other countries was in a sense paralleled by a theoretical reality, that of a World governed by a family of princes whose hierarchic head was the Emperor of Constantinople.

The ancient doctrine defining the antithesis between the Empire and the barbarians has long been familiar, as has its prolonged survival in Byzantium; the only thing needed to complete our understanding of the interpretation given to this doctrine in medieval Byzantium would be to assemble and classify all the characteristic passages from the authors of the time and the texts of the Russian chronicles, which adopt the traditional Byzantine phraseology for describing the situation of the Russian state vis-à-vis the Turkish and Mongolian peoples. The studies which reconstruct the “family of princes” theory created at the Court of Constantinople are much more recent. Thanks to these works,1 we no longer are confronted with the seemingly insurmountable contradictions, between the notions of vassalage and independence with regard to Byzantium, which there were good reasons to apply simultaneously to a single state: for instance, could the princes of Kievan Russia enjoy political independence de jacto and at the same time be subordinate to Byzantium in the ideal “family” of princes, headed by the emperor? Moreover, these studies have detected a central fact: that the growing importance of the independent states around the Empire had led the Byzantines to favor and to systematize a doctrine which reflected the political reality of the Middle Ages more faithfully than the theory of the Empire-barbarian antithesis. This doctrine, now referring not to whole peoples but only to heads of governments, no longer rates them uniformly as “tyrants” (as they appeared when they were considered from the point of view of an Empire opposed to the barbarian world), but confers on them the honorific titles of son, brother, and friend of the basileus. The former “tyrants” are brought into the family circle of the Emperor of Byzantium himself, and he reserves for himself only the dignity of pater familias.

This doctrine was especially useful in that it defined the relations between the Byzantine monarchs and other princes in peacetime and as a consequence provided a constructive principle for organizing a world-wide expansion of the Byzantine political influence without recourse to conquest (whereas the old doctrine of the universal Empire as the antithesis of the barbarians assumed implicitly the final conquest of the latter by the head of the Empire). The Byzantine chancellery could thus use the “family of princes” theory quite openly in the official documents which it issued and brought to the knowledge of foreign princes. When addressed as sons, brothers, or friends of the basileus, the foreign princes regarded these terms less as a violation of their sovereignty than as a recognition of their actual political power, which, on an ideal level, was thus integrated into a universal political system.

The essor of the “family of princes” theory is a result of the consolidation of the national states around Byzantium, but it also owes something to Christian ideas. Up to the end of the Empire the Byzantines took a certain satisfaction in reproducing the accepted variations on the antibarbarian theme, inherited from pagan antiquity, but it was always in connection with invasions or foreign wars. On the contrary, outside of these armed conflicts they delighted in making the most of a foreign prince’s (for instance a Bulgarian’s) title as son or brother of the reigning emperor, and it cannot be doubted that for the tsars of Bulgaria as for other “barbarian” princes, it was their conversion to Christianity which made this new Byzantine attitude possible. The official application of the theory of the “family of princes” by the Byzantine chancellery coincides with the adoption of a generalized policy of sending Christian missions from Constantinople and with the growing progress of Christianity in the countries bordering on the Empire. Indeed, this notion of a “family of princes” was an instrument of Byzantine diplomacy (this political system did not permit a state to withdraw from subordination to Byzantium without the shameful stigma of a traitorous revolt against the head of a spiritual family), and it in no way excluded the non-Christian (Muslim) princes from the ideal association of states; but the primary constant of Christian thought is clearly manifest in the usage of the two superior titles – “son” and “brother” – which are reserved for Christian princes only. These are, moreover, the only titles which express a real bond of relationship (to show the spiritual character, but also the reality – on the religious level – of this relationship, the epithet πνϵυματικός, that is, “spiritual,” was added to the title “brother” or “son” of the emperor). Sometimes – for the first princes of a dynasty to be converted – the basileus became the godfather and the prince baptized took the name of his spiritual father, the emperor: Boris of Bulgaria was called Michael after Michael III; Vladimir of Russia was called Basil after Basil II. The non-Christian princes were taken into the ideal system of the “family of princes,” but with the title of “friend.” This therefore left them outside the spiritual and Christian family which formed the nucleus of the association of princes imagined by the Byzantine chancellery. The last point, as we shall see, is of considerable importance. It is this which permitted the theory of the “family of princes” to be introduced into the corpus of traditional doctrines of the Christian Empire.

It has been recently pointed out that the Byzantine theory of the universal “family of princes” was not the first to imagine a government of the world by “brother” princes.2 There were antecedents: the emperors of Rome and the kings of Persia, under Galerius, then under Maurice and Phocas; the universal Roman Empire governed by the Tetrarchs, the first two of which were brothers and the other two sons of the Augusti.3 Even farther back, at the court of the Ptolomies (second century B.C.), dignitaries not related to the royal family bore the title of συγγϵνής, “relative,” with the honors which this theoretical relationship implied, including the divinization reserved for real members of the reigning dynasty, and as early as the Hellenistic courts the bonds of fictitious relationship were defined with the words ἀδϵλϕός, “brother” and πατήρ, “father”; finally, as later in Byzantium, the ϕίλοι, “friends” of the king, occupied a rank inferior to that of the “συγγϵνϵι̂ς,” “relatives.”

But the Roman-Persian antecedent is radically different from the Byzantine system of the Middle Ages in one essential feature: the two sovereigns are not brothers unless they share the universe geographically. It is a purely political conception, without religious background, and, in this respect Byzantine practice at the time of the Macedonians and the missions to the Slavs does not derive from the old theory, or at any rate, if there is any recollection of these antecedents, they are given a religious basis, under the probable influence of the mass conversions of the barbarian tribes. In contrast, if not as a direct source of inspiration for the Byzantines of the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries, then as a distant antecedent of a “family of princes” with a religious basis, the example of the Ptolomies and the Tetrarchs should be recalled: in both cases the whole reigning family acquired, from the heads of the families who held the supreme power and represented gods incarnate, a moral unity which is essentially religious. These families, united by a “spiritual” bond, are in some sense extended to the other world, the abode of the gods who protect and direct the fictitious “family” of the rulers.

For medieval Byzantium one could assume a similar extension. But a text which I should like to add to the dossier of “family of princes” theory makes it more clearly understandable, and in a very curious way. This text is in the Institutio Regia of Theophylact, Archbishop of Ochrid in the time of the Byzantine reconquest of Bulgaria. The great intelligence, the broad learning, and the vigor of this prelate are well known. Being responsible for directing the ecclesiastical affairs of Slavicized Macedonia for the benefit of Byzantium, he proved to be well aware of the work of his predecessors from the time of Great Bulgaria and of the general problems which the relations between the Empire and its neighbors posed. He did, once, to be sure, reproduce in a piece of brilliant rhetoric, the whole arsenal of ancient notions and terms referring to savage barbarians.4 But in other writings he gave evidence of being well informed about the successful missions of St. Clement, disciple of St. Cyril, among the Slavs of Macedonia and on the pro-Christia.n activities of Tsar Boris.5 In the Institutio Regia which we shall quote, it is for the benefit of a young prince, Constantine, son of Romanus IV Diogenes, that Theophylact explains the principles of imperial government, and he happens, on this occasion, to contribute some useful specific information on the historiosophic thought of the Byzantines.

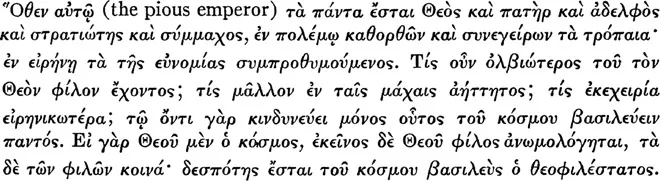

In chapter 12 of the second part of his Institutio Regia (Migne, PG 126, 273, 276), Theophylact writes, to show that piety was necessary for the emperor:

In other words, for the pious Emperor of Byzantium, God is simultaneously Father and Brother, head of the army and comrade in arms, He Who in time of war ensures victories and in time of peace just government. Above all, for the Emperor God is a friend; the basileus has the Master of the universe as a friend, and as a result – are not the goods of friends common? – the basileus who is loved by God becomes a universal sovereign himself.

In this suggestive passage, one notes first of all the use, one after the other, of all the terms which serve in the language of the imperial chancellery to designate the different members of the “family of princes”: πατήρ, ἀδϵλϕό, ϕίλος. One sees, on the other hand, that in this context these words are not employed in their usual senses but in the interpretation given them by Imperial documents, for they are used in association with other terms of the political vocabulary, στρατιώτης, “chief of the (Byzantine) army” and σύμμαχος, “subordinate allied fighter (foreign auxiliary leader of Byzantine armies).” Therefore God, who is at once father, brother, head of the army, fighting ally, and friend of the emperor, guarantees the latter supreme power over the world, just as, on a terrestrial level, this power rests outside the Empire on the whole group of members of the “family of princes,” his brothers, sons, and friends, subordinated to his patria potestas; and within the Empire on the heads of his armies, regular and auxiliary.

This remarkable text is in conformity with the basic ideas of the Christian Empire and only extends the principles established in the time of Eusebius and faithfully maintained in Constantinople through the centuries to ...