![]()

1

Introduction

A central characteristic of the postwar period has been the rapid expansion of international trade. Whereas real economic output increased by 3.7 percent per year on average from 1948 to 1997, trade grew at a much greater rate of about 6 percent per year during this period. From 1985 to 1997 the ratio of trade to gross domestic product (GDP) rose from 16.6 to 24.1 percent in developed countries, and from 22.8 to 38 percent in developing countries.1 To manage this growing trade interdependence, the major economic powers gradually established a global trade regime. Regimes are institutional arrangements for managing problems and promoting stability and cooperation among interdependent states. Most commonly, regimes are defined as “principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations.”2 International organisations are “physical entities possessing offices, personnel, equipment, budgets, and so forth” that often provide a venue or setting in which international regimes can operate.3

In some sectoral areas, studies of an international regime may focus on a range of associated international organisations, or formal and informal institutions. For example, one study on the environment defines a world environmental regime as “a partially integrated collection of world-level organizations, understandings, and assumptions that specify the relationship of human society to nature.”4 However, in sectoral areas such as trade where there is a predominant international organisation, Robert Keohane maintains that in practice “organization and regime … may seem almost coterminous.”5 Most international relations scholars have in fact described the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) from 1948 to 1994, and the World Trade Organization (WTO) since 1995, as being “virtually coterminous” with the global trade regime;6 and some studies of global trade specifically refer to the “GATT/WTO regime.”7 Nevertheless, as early as 1969 the trade law specialist John Jackson expressed an alternative view, arguing that global trade management involved a wide range of institutions in addition to the GATT:

International regulation of international trade is … an extraordinarily complex and muddled affair, involving a wide variety of organizations and institutions … when one considers GATT, it is necessary to relate it to the mosaic and ever-changing picture of other international institutions. In some cases the institutions complement each other in important ways … In other cases the subject-matter attention of these institutions overlaps.8

Although the GATT/WTO has certainly been the key international organisation embedded in the global trade regime, this book builds upon Jackson’s view of global trade governance. A major thesis of this book is that our understanding of the global trade regime will be greatly enhanced if we devote more attention to these “other” trade-related institutions and their relationship to the GATTAVTO. This study gives primary emphasis to three institutions that have had a significant impact on global trade relations: the Group of Seven/Group of Eight (G7/G8), the Quadrilateral Group (Quad), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). We devote a smaller amount of space to institutions representing developing country interests such as the Group of 77 (G77) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), because they have been far less influential in the global trade regime. However, developing countries have had a more active and important role in the global trade regime in recent years, and the latter part of the book discusses the role of North-South coalitions such as the Cairns group in the GATT Uruguay Round.

Of the regional trade agreements (RTAs), this book devotes attention only to the European Union (EU), because over the years the European Commission has “established itself as the negotiator for the European Union … on trade issues, but always operating under the watchful eyes of the member governments.”9 The EU has a special status among RTAs in the three institutions we focus on in this book: the G7/G8, the Quad, and the OECD. Most importantly, the members of the Quad are the trade ministers of the United States, the EU, Japan, and Canada. Furthermore, since 1978 the Presidents of the European Council and Commission have been regular participants in the G7/G8 summits (the relationship between the Commission and the Council in European external relations is disussed in Chapter 4). The European Commission is not a member of the OECD. However, Supplementary Protocol 1 of the OECD Convention indicates that the European Commission “shall take part in the work of that Organisation.”10 This protocol gives the EU more privileges than other international organisations, which are limited to having observer status in the OECD. In effect, “the Rules of Procedure, and the subsequent practices, give the Commission, which has its own Delegation in Paris, practically the same rights as a member country.”11 Thus, the European Commission is a member of various OECD committees and working groups such as the Development Assistance Committee and the Working Party of the Trade Committee. The main privileges the European Commission is denied as a nonmember of the OECD are the right to vote and the right to participate in the formal adoption of Acts of the OECD (as a nonmember, the Commission also does not contribute to the general budget).

Although we refer to other institutions throughout the book, they are discussed only for illustrative purposes. Thus, this book systematically traces the changing role in the global trade regime only of the G7/G8, the Quad, and the OECD. This chapter explains why we focus primarily on these three institutions, and provides a general background discussion of the relationship of the GATT/WTO to other institutions in the global trade regime. Subsequent chapters examine the historical role of the G7/G8, the Quad, and the OECD in the post-World War II period.

The Role of the G7/G8, The Quad, and the OECD in the Global Trade Regime

Although regimes are usually defined in terms of principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures, most studies of international regimes in reality tend to focus only on the first three of these characteristics. Regime theorists have therefore directed their attention to the international organisation that has primary legal responsibility for upholding trade regime principles, norms, and rules: the GATT/WTO. Nevertheless, it is not sufficient to limit one’s study to the GATTAVTO when examining the decision-making procedures of the global trade regime. Decision-making procedures are “prevailing practices for making and implementing collective choice,”12 and collective choice in the global trade regime develops as a multi-layered process through discussion and negotiation in a wide array of formal and informal institutions.

It is important to direct more attention to decision-making procedures in the global trade regime, because these procedures can have a significant effect on the development and evolution of regime principles, norms and rules. For example, two basic trade regime principles are nondiscrimination (including most-favoured nation treatment and national treatment) and reciprocity. Although developed countries maintain that these principles are essential for creating “a level playing field,” developing countries have argued that the nondiscrimination and reciprocity principles are biased in favour of the rich countries because they support “equal treatment of unequals.” The developed countries have also been the main supporters of a trade liberalisation principle. Nevertheless, they have been most influential in deciding when exceptions should or should not be provided to this principle. As we discuss in Chapter 5, GATT Articles XI and XVI were designed to outlaw import quotas and export subsidies, but agriculture was initially treated as an exception to these regulations to conform with provisions in the U.S. farm program. When the European Community established its highly protectionist Common Agricultural Policy it became fully committed to these exceptions. Textiles and clothing have also been treated as an exception to the trade liberalisation principle, largely because the textiles sector in the South has presented a major threat to the textiles sector in the North. In 1974, the North successfully pressured the textiles-exporting developing countries to join in the Multifibre Agreement (MFA), which ironically was negotiated under GATT auspices. The MFA “introduced generally restrictive rules, as well as the principles of quotas and a selective safeguard mechanism.”13 Thus, decision-making procedures have ensured that the principles, norms, and rules (and exceptions to them) in the global trade regime largely reflect developed country interests and objectives. A “development principle” addressing the concerns and needs of developing countries gradually emerged in the GATT, but it was always subsidiary to other trade regime principles such as reciprocity and nondiscrimination.14

When the Final Act establishing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade came into effect in January 1948, 23 countries were contracting parties in the GATT. (This book uses the less accurate term GATT members for the sake of brevity.) Only 10 of the original 23 GATT members were developing countries, and they had little influence. Although 20 developing countries had joined the GATT by 1960, only 7 of them participated in the 1960-61 Dillon Round of GATT negotiations.15 Until the early 1960s, the GATT therefore had the characteristics of a small club dominated by the developed countries. The GATT could readily perform most of the decision-making functions in the global trade regime during this early period, because the developed countries were the major traders. In the 1960s, however, developing countries joined the GATT in much larger numbers. As Table 2.1 (page 33) shows, 62 countries participated in the 1964-67 GATT Kennedy Round, which was a marked increase from the 26 countries participating in the previous Dillon Round. The growing membership of the GATT interfered with its small club-like atmosphere, and pressures therefore began to develop in the 1960s to establish smaller groups to facilitate consultations among the major developed country traders. Thus, one of the 3 main institutions discussed in this book, the OECD, was established in the 1960s. It was also in the 1960s that the G77 and UNCTAD were formed, highlighting the division between the North and the South.

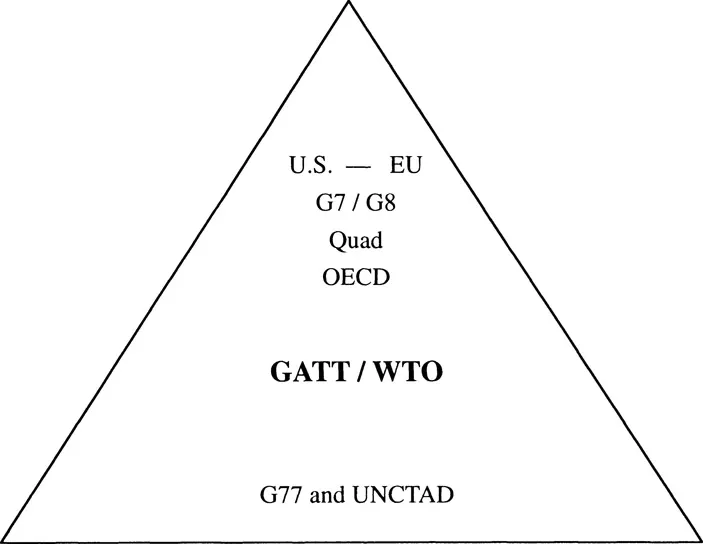

As the GATT membership increased and became more diverse in the 1970s and 1980s, the major developed country traders sought additional smaller groupings to facilitate decision-making, both within and outside of the GATT. Within the GATT, a Consultative Group of Eighteen (CG.18) was formed on a temporary basis in 1975, and then made a permanent body in 1979; and other groups such as the “green room” sessions were also established. However, for reasons discussed later in this chapter, the developed countries felt that these groups within the GATT did not adequately facilitate decision-making on trade-related matters. In the 1970s the developed countries established the G7 outside of the GATT which deals with a wide range of issues including trade, and in the 1980s the developed countries established the Quad which focuses specifically on trade. Figure 1.1 shows that the decision-making procedures of the global trade regime are in many respects pyramidal, with developed country institutions near the top of the pyramid, and developing country institutions near the bottom. Thus, the G7/G8, the Quad, and the OECD have occupied important positions at the upper levels of the trade decision-making pyramid. Gilbert Winham has described the GATT Tokyo Round negotiations as a pyramidal process, in which

Figure 1.1 Pyramidal Structure of the Global Trade Regime

issues tended to be first negotiated between the United States and the EC [European Community]; and once a tentative trade-off was established the negotiation process was progressively expanded to include other countries. In this way co-operation between the United States and the EC served to direct the negotiation.16

Whereas Winham’s description of a pyramidal structure refers to GATT/WTO negotiations, this book broadens the discussion of pyramidal structure to examine the relationship among several formal and informal institutions in the global trade regime. The G7/G8 and the Quad are placed above the OECD in the global trade regime pyramid because only the most economically important of the OECD members are included in these more select institutions. Furthermore, the G7/G8 which meets at the heads of government and state level is higher on the pyramid than the Quad which meets at the trade ministers level. As we will discuss, the United States was clearly the hegemonic actor in the global trade regime in the 1950s and 1960s; but its trade hegemony has declined since that time. Figure 1.1 shows that the European Union now occupies a place at the top of the pyramid along with the United States as the most prominent actors in the global trade regime.

The important point to note about the pyr...