![]()

PART ONE

Grub Street

![]()

Chapter 1

Grub Street: an Introduction

Grub-street: a street near Moorfields in London, much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called grubstreet.

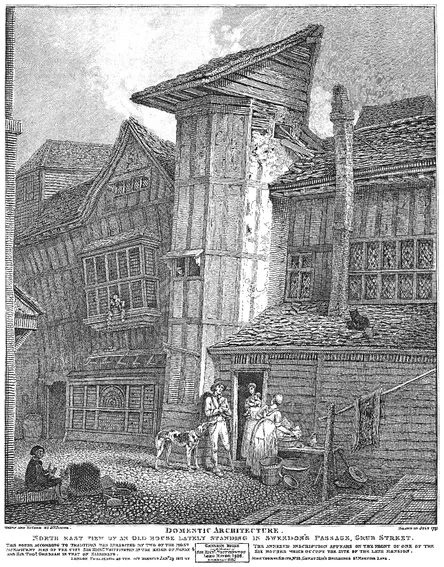

Johnson’s Dictionary, 1755

Grub Street (Figure 1.1) was a real place, as real as Fleet Street. Its name came from the refuse ditch (grub) that ran alongside. Built on marshy ground, Grub Street was a notoriously unhealthy place, prone to epidemics. Cripplegate had the highest death rate during the 1665 Plague, with over 6,000 killed by the plague in three months alone. As the land commanded a poor price, cheap lodgings were easy to find. It was an area of poverty and vice, teeming with disreputable tenements, mean courts, low alehouses and dark alleys, that Fielding could have been describing when he wrote:

Whoever indeed considers … the great irregularity of their buildings; the immense number of lanes, alleys, courts, and bye-places; must think, that, had they been intended for the very purpose of concealment, they could scarce have been better contrived. Upon such a view, the whole appears as a vast wood or forest, in which a thief may harbour with as great security, as wild beasts do in the deserts of Africa or Arabia; for by wandering from one part to another, and often shifting his quarters, he may almost avoid the possibility of being discovered.1

Jonathan Wild set up his first thieving den just round the corner2 and Mrs Habbiger ran a bawdy house in Turks Head Alley, which led into Grub Street.3 The Wandring Whore, Number 2, 5 December 1660, lists Mrs Bull, Mrs Halfpenny and Mrs Harrison as Crafty Bawds operating from the Three Sugar-loaves, Grub-street, and ‘Mrs Wroth, Grub-street’ as a Common Whore. Grub Street was a place to hide from one’s creditors, or the law, and was not safe at night: ‘On Monday Night a Journeyman Shoemaker was set on by two Footpads in Grub-street, who knock’d him down and robb’d him of 3s.6d. and two Knives.’4

Grub Street also had a crude sense of humour. Ned Ward reported the existence of a Farting Club in Grub Street, ‘established by a Parcell of empty Sparkes about thirty years since in a Publick House in Cripplegate Parish and meet once a Week to poyson the Neighbourhood, and with their Noisy Crepitations attempt to outfart each other’.5

Unfortunately, there is little evidence to support the picturesque myth that the garrets of Grub Street played host to a colony of impoverished writers. It is known that some of the more destitute writers and printers of ‘mean publications’ lived in the area around Grub Street. Journalists too: Defoe was born just round the corner in Fore Street and died in Ropemakers Alley, one of the many dark passages that fed into Grub Street; and John Dunton lived not far away in Jewen Street. Little Britain, the book-publishing centre of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, was only half a mile away. In the 1640s and 1650s, with the explosion of newsbooks and other unlicensed publications, the warrens surrounding Grub Street were the hiding places of fugitive printers lugging their moonshine presses from one garret to the next, trying to keep one step ahead of the authorities.

Grub Street Hacks

The term Grub Street was first recorded in its non-geographical sense in 1630. It became more prevalent during the Civil War when both sides paid the authors of newsbooks to fight a paper war on their behalf. With the formation of political parties after the Restoration, the term became established to describe journalists, political pamphleteers and other writers of ephemeral publications who, with neither a private income nor a wealthy patron, wrote for money.

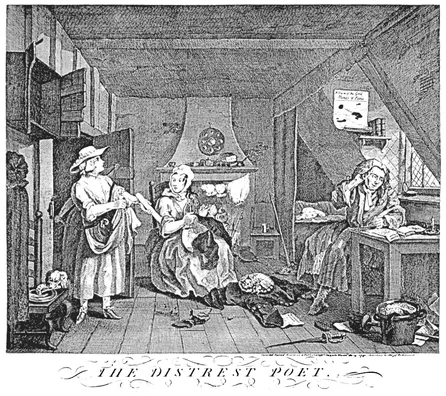

Grub Street is a metaphor for the hack writer. The word ‘hack’ derives from Hackney, originally meaning a horse for hire and later a prostitute, a woman for hire. Finally, it was applied to a writer for hire, a newspaper writer or a literary drudge. Paid by the line, scratching a precarious living from the lower reaches of literature, including journalism, the Grub Street hack received no public acclaim, other than the sneers and jibes of his more successful contemporaries who, by a mixture of ability and sycophancy, had found the security of a patron. His life was pictured by Hogarth in the Distrest Poet (Figure 1.2). His condition was described by Ned Ward as

very much like that of a Strumpet … and if the reason be requir’d, why we betake our selves to be so Scandalous a Profession as Whoring or Pamphleteering, the same excusive Answer will serve us both, viz. that the unhappy circumstances of a Narrow Fortune, hath forced us to do that for our Subsistence.6

And his fate was described by Macaulay:

To lodge in a garret up four pairs of stairs … to translate ten hours a day for the wages of a ditcher, to be haunted by bailiffs from one haunt of beggary and pestilence to another, from Grub Street to St George’s Fields, and from St George’s Fields to the alleys behind St Martin’s Church, to sleep in a bulk in June and amidst the ashes of a glass-house in December, to die in an hospital, and to be buried in a parish vault.7

1.2 The Distrest Poet: Hogarth’s portrait of the Grub Street hack

The traditional view of the Grub Street hack as feckless, living in a garret, and scribbling furiously by rush-light to earn the next bottle of gin and to get his belongings out of pawn – the eighteenth-century equivalent of the jazz musician – is exemplified by Samuel Boyse, who wrote for the Gentleman’s Magazine. Boyse, by all accounts a thoroughly dishonest and disreputable rogue, was generally paid by the line for his efforts as a poet, translator and literary jack-of-all-trades. He was said to be ‘intoxicated whenever he had the means to avoid starving’ and, ‘after squandering away in a dirty manner any money which he had acquired’, was known to ‘pawn all his apparel’. On at least one occasion he was found shivering in his garret, naked in bed with two holes cut in his blanket so that he could write. Whenever he pawned his shirt, ‘he fell upon an artificial method of supplying one. He cut some white paper in slips, which he tyed round his wrists, and in the same method supplied his neck. In this plight he frequently appeared abroad, with the added inconvenience of want of breeches.’8

Accounts of his death at the early age of 41 vary. One story has it that he was run over by a coach while lying drunk in the street. If this is true, it was perhaps a fitting end. I like the man, and I hope he did not suffer.

Unable to secure the custom and favour of the great, journalists stood outside polite society. In the eyes of the establishment, they were a semi-criminal class. They were vulnerable to the law, especially the law of seditious libel, and their uncertain way of life, with its irregular payment and lack of security, compelled them to live in the lower quarters of the city, such as the Grub Street area. They could only make their living in a hackney kind of way by prostituting their pens to the highest bidder: Tories one day, Whigs the next, and all the time suffering harassment from authority.

We know tantalizingly little about the anonymous journalists who wrote for the eighteenth-century newspapers. Perhaps the description of journalists in a letter to the printer in Say’s Weekly Journal for 25 April 1767 contains some degree of fictionalized truth. The writer explains that he was sitting in the Camden coffee-house in Mitre-court, ‘a house that I use because there are more news-papers taken in than at any other coffee-house in England’, when his attention was drawn to two other customers:

They seemed to be about thirty, and were dressed in that manner which is generally termed the shabbily genteel … that is, every article in their dress was in the newest taste, but had undergone a great deal of service, and appeared to be somewhat worse for wearing … the black stock about the neck of the shirt, rather sable at the wristbands, supported a strong supposition, that it was worn to the full as much as from necessity as inclination; as for the coat, nothing could be better brushed, the threads might be counted without the least assistance of spectacles, and it buttoned amazingly close about the body of the owner, as to do the highest credit to the taylor’s ingenuity; the breeches, which formerly were a black knit, had been newly inked over, to refresh the colour, and the baging of the stockings about the ankles, easily declared, that the gentlemen were proficients in economy … [the writer describes his mounting horror when he overhears one of the customers ask the other] … how he had amused himself in the course of the week, ‘Why’, replied the other, ‘I picked a few pockets in Fleet-street, broke open a house in High-Holborn; this evening I purpose to commit a murder in the neighbourhood of Newington, in the morning I shall set a stable on fire, and burn half a dozen horses in Ratcliffe-highway.’ … the person who asked the first question, being interrogated in turn, he thus gave his companion an account of his pretty performances. ‘As for me I have done a great deal more, on Monday, I ravished a girl of seven years old in Chancery-lane, and thrust out a publican’s eye with a roasting-fork, in Barbican; on Tuesday I stole a child from its parents in Smithfield, and after stripping it, got five shillings from a beggar-woman for my theft, who broke its back immediately, to excite the compassion of the public; the consequences are admirable; for, on Thursday the mother cut her throat in a fit of despair, for the loss of her infant, which gave the father so terrible a shock that he is raving mad in a private repository near Islington; the same day also, I robbed a western mail; stole the communion plate out of a church; and formed a conspiracy for an unnatural crime against a dignified clergyman’ … There was no hearing any thing further, I started from my seat, and there being a good deal of company in the room, cried out, ‘Gentlemen, I demand your assistance in the King’s name, to apprehend the two desperate villains at this table; I can charge them both with robbery and murder, on their own confession.’ … [Having secured the two men, the writer repeated to the company what he had overheard, when one of the accused exclaimed] … ‘Lord, Sir, you are certainly out of your senses, or strangely mistaken in the nature of our conversation. We commit robberies and murders – no, no Sir, – we only commit them with pen and ink. We are paragraph-makers, and were merely telling each other in our usual way, what inventions we had used to gratify the curiosity of the public, during the last week, with extraordinary intelligence. Here to convince you’, continued he, pulling out a parcel of papers from his pocket, full of robberies, murders, adulteries, rapes, impositions, political squibs, theatrical puffs, broken bones, and inferior casualties.

Journalism was not an honourable profession in the eyes of the establishment, nor, indeed, in the eyes of their fellow hacks, especially in Walpole’s time when the newspapers entertained their readers with a glorious display of personal abuse, hack versus hack, in the battles between the ministerial and the opposition presses:

The Common Sense of last Saturday tells the Daily Post that he is a Pyrate, a Pickpocket, and a Highwayman and treats his Brother-Scribler in al...