![]()

ALFREDIAN GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY

![]()

Chapter 9

Alfredian government: the West Saxon inheritance

Nicholas Brooks

The emphasis in the title of this chapter lies on the word ‘inheritance’. The underlying question is: how far were Alfred’s governmental and administrative practices devised by the king himself with the aid of his court advisers, or were they standard procedures that he had inherited from previous West Saxon kings? Was Alfred an innovator in government or merely an able transmitter of an old inheritance? We have recently been reminded of the antiquarian myth-making that turned King Alfred into the founder, not only of the University of Oxford, but also of hundreds and tithings, of the royal navy, of county councils and of much else that was held sacred in the British political, constitutional and educational worlds between the thirteenth and the nineteenth centuries.1 But more recent historians have also found signs of new beginnings in the rule of King Alfred. Thus the late Henry Loyn saw this reign as marking the watershed between the primitive early Anglo-Saxon polities and what he understood as the ‘territorial state’ of later Anglo-Saxon England;2 while Patrick Wormald has conceived the reign as a starting-point for ‘the making of English law’.3 But it must be confessed that, despite the interpretative models of such luminaries, it is still not easy to assess Alfred’s impact upon royal government. We can see something of the king’s political and military activities in the pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and of Asser’s Life of Alfred; we can see the results of his administration in the surviving coins bearing his name and in the boroughs that resisted Danish assault in the later 880s and early 890s. But it is singularly difficult to say anything about the governmental processes involved.

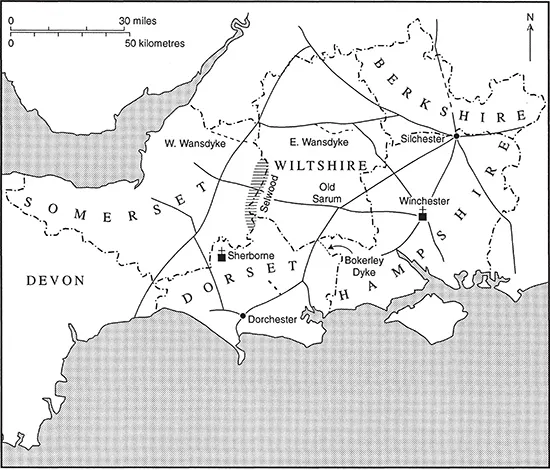

There is, moreover, reason to believe that the administration of the core West Saxon shires (Fig. 13) of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorset and Somerset by ealdormen appointed by the king had been in existence throughout the ninth century, that is since the reign of Alfred’s grandfather, Ecgberht (802–39). Very possibly it goes back further to the 750s, when the Chronicle first mentions Hampshire (Hamtunscir), and when praefecti or principes first attest the charters of West Saxon kings.4 It is even possible that the structure of shires run by ealdormen actually dates from the reign of King Ine (685–725); in that case the references in Ine’s laws to scirmen, and to ealdormen and their scirs, could be accepted as referring to this same system.5 Otherwise we must regard them either as a later updating (perhaps when the code had been appended to Alfred’s lawbook) or as referring not to the shires familiar to us in later times but rather to an older system of smaller units of lordship known under various names in different parts of England (regiones, provinciae, lathes, leets, rapes, Danelaw hundreds and so on), but as ‘shires’ in northern England and south-eastern Scotland.6

Of the operation, regularity and procedures of these courts, of the appointment and dismissal of their officers, of the arrangements for the capture of criminals and of the enforcement of law upon recalcitrants – in short of the machinery of an incipient state – Alfred’s laws tell us nothing. We are left to conclude that whatever new regulations Alfred and his witan may have ordered to be enforced,7 they did not alter long-standing arrangements by which local folk-moots under king’s reeves and ‘shire’-moots under the king’s ealdormen administered the law for their districts. Such royal agents (or their sons) might need to be bullied to attend King Alfred’s school in order to resuscitate (or to create) the ability to read his laws in English;8 they might even need to be dismissed for treachery; but the fundamental administrative machinery of the kingdom was, it would seem, an ancient one which Alfred (like his son) left intact. Seemingly he had no reason to make specific reference in the Domboc to what was long established and well understood.

Alongside the paucity of evidence for government in the laws and in the Burghal Hidage, we also find a scarcity of acceptable royal charters or diplomata from Alfred’s reign. Only ten have any call upon our attention.9 No good case can therefore be made for Alfred as an effective administrative reformer, let alone as a ‘founder’ of English (or even of West Saxon) government. His gifts of leadership may have lain in man management, on the field of battle and in intellectual discourse, rather than in bureaucratic reform. Indeed there is a temptation to suspect that the king’s rule was indeed both simple and primitive. Certainly there is an attractive informality about a king who corroborated the key judgement of one of his ealdormen in a dispute over a substantial estate at Fonthill while washing his hands in his chamber at Wardour (Wiltshire).10 Alfred was not, perhaps, a man who needed to take refuge in elaborate trappings of government procedure and the formalities of etiquette.

Some elements in the organization of the West Saxon court certainly do go back to the reigns of Alfred’s father, Æthelwulf, and of his grandfather, Ecgberht (802–39). Restricting the royal succession in 839 to Æthelwulf, the nearest heir of Ecgberht, and to Æthelwulf’s sons at the subsequent royal deaths in 858, 860, 865 and 871 marks the successful stabilization of a new dynasty. One element in this decisive change from the previously much more fluid succession arrangements was a process of committing the archbishops of Canterbury and all the ‘Saxon’ bishops (of London, Selsey, Winchester and Sherborne) to the support of Ecgberht’s dynasty. The allegiance of these bishops was secured at a council held at Kingston in 838 and in subsequent confirmations at Wilton and æt Astran in 839; the process, it would seem, led to a new manner of treating the southeastern territories of Kent, Essex, Surrey and Sussex as a single kingdom held as an appanage by a son of the king.11

The assemblies of the kings with their West Saxon nobles, lay and ecclesiastical, were not only occasions for the affirmation of loyalty to a chosen heir, but also for the exercise of royal government. Professor Keynes has recently identified a coherent single tradition in the diplomatic of the extant West Saxon royal charters in the period from c. 840 to 899.12 Whereas in Kent, in Sussex, or in the Hwiccan territory of Mercia, diocesan writing offices seem to have been responsible for drafting the bulk of the extant ninth-century royal charters, Keynes has shown that grants in the name of King Æthelwulf and of his sons relating to land in Hampshire, Wiltshire, Berkshire, Somerset or Dorset share certain common features in their formulation. This common diplomatic tradition may plausibly be attributed to the work of ecclesiastics serving in the king’s following or household. Certainly there is no trace in Wessex of any distinction between a Winchester and a Sherborne diplomatic, such as we can show throughout the ninth century between the charters granting estates in the dioceses of Canterbury and Rochester, even when Kent was under West Saxon rule.

It is instructive that these West Saxon charters show the ninth-century kings meeting their leading subjects – bishops, ealdormen (duces), and the king’s thegns (ministri) – in great councils or witans held on the great Christian festivals, especially on St Stephen’s day (26 December) following the celebration of Christmas and on Easter Sunday. These formal councils appear to have gathered at a relatively small number of royal vills or centres. Dorchester is much the most favoured venue in the extant documents; but [Sout]hampton, Winchester, Kingston, Amesbury, Somerton, Micheldever, Woodyates, and the unidentified royal vills of Suðtun (one of the many Suttons) and Andredeseme (in the Weald?) also appear. The records of these major meetings of the royal court in ninth-century Wessex take us to the political heart of the kingdom and to its major formal occasions. These charters record gatherings where (we may suppose) major issues of politics, warfare, peace-making and law-making were also resolved and more generally where royal power and patronage were exercised.

The majority of the extant West Saxon charters of the period from 839 to 871 are grants to important lay nobles, mostly of the rank of ealdormen, and usually granting them substantial estates within their own ealdormanries. A grant by King Æthelred of ten hides of land at Wittenham (Berkshire) to princeps Æthelwulf in the year 862 may serve as a good example of the rewards for service received by the high nobility of ninth-century Wessex.13 We only know of such grants, of course, if the estates later happened to come into the hands of the Church; in this case Wittenham and its charter passed into the possession of the reformed monastery of Abingdon. The beneficiary of the charter, Ealdorman Æthelwulf, had been the Mercian ealdorman of Berkshire; he had attended the witans of the Mercian kings, Wiglaf and Berhtwulf, at least from 836 until c. 845; but when the shire had been handed over to West Saxon control in the 850s, Æthelwulf had transferred his allegiance to the West Saxon dynasty and had thenceforth attended West Saxon councils. He was to die fighting alongside King Æthelred and his brother, the ætheling Alfred, against the mycel here at Reading in 871. That his family felt that his roots remained Mercian may be suggested by the fact that after the battle his body was spirited away for burial at Northworthig (Derby);14 but there is no hint in the Chronicle that his loyalty to the West Saxon dynasty, rewarded by such grants, had ever wavered.

If we turn from the gatherings of the itinerant West Saxon court to the administration of the kingdom at the local level, then here too we find that Alfred inherited and continued an existing system, namely of shires with smaller districts (regiones) with...