![]()

Chapter 1

Settings and Signposts: A Soul Perspective, Soulful, Ensouling and Soul-force

In this writing project I have ‘girded my loins’, so to speak, to write about community practice through the lens of this somewhat taboo, and ancient concept ‘soul’. Many have taken this path – from Jung, Hillman and other archetypal psychologists, through to those in the more critical-social tradition, such as Beradi and Rose. I accompany them as a community worker. In doing this I come with two major settings in mind.

Setting #1: Soul and Community Practice

First, there is a focus on soul and associated concepts as community work practice, as is hopefully already clear. Soul offers a perspective, a way for community practitioners to be and do their ‘work’. It is practice that is both given meaning, and also as embodying particular kinds of performances, that can be construed as more careful, mindful, responsive, spontaneous, intimate; and as practice requiring attention, imagination and creativity. It is practice that is in some way about the capacity to see, and tap into, the movements, energies and connections available in the world that animates or reanimates who we are as individuals and groups, that in turn ensures vitality – and all within an ethical frame, albeit one often disrupted by the trickster ‘other’. One could say I am interested in how practitioners ‘keep themselves in shape’ to maintain such capacities.

In the Introduction this practice setting was highlighted through attention to soul as both metaphor and myth. The practice element of community work requires both attention to the metaphoric ‘nudges of the soul’ (those inner movements of the community worker), and also the archetypal energies at play within groups and communities – the mythic dimension (the outer movements, that are often subtle and subterranean, hidden beneath the surface of social processes).

Setting #2: Soul as Analytical Concept

Secondly, soul is used as the core analytical concept in thinking about how people might be animated in collective activity and action, or/and in turn be conscious of how people are shaped to act by broader field of actors and discourses. In this sense, soul alludes to the notion that in some way most collective action is animated by energy. It is energy that fuels people’s capacity to get involved and stay the course. Animating energy in turn, like desire, is theorised as both a force (something flowing through individuals and groups – those archetypal, mythic energies, the deep culture perhaps), and as a field, shaped by a range of competing forces and discourses in and around our lives (myths too, propagated and assembled by discursive ‘regimes of truth’, but also economic (material forces), political and social). Soul is then imagined in a similar way, as an embodied energy, that is also shaped by forces and discourses that people are constantly in relationship with.

For example, in community work practice it is reasonably well known that if a practitioner approaches a community with questions such as, ‘What are your needs or problems?’ energy will quickly be depleted. The discursive frame will shape the energy available. Soul, as individual and the collective body animated, will potentially sink as people sense an overwhelming array of needs. However, if questions to do with vision, opportunity and aspiration are asked, then there is a greater chance of animated bodies as people are enlivened by the possibilities. The questions would enhance what I have alluded to as spirited practice (metaphorically and mythological these would be upwards energies).

However, if questions to do with people’s story, their deeper desires and even social pain are asked, then a different kind of animated social body starts to emerge – one that is earthy, grounded, strong even (imagined as downwards energy, earthy). If people get close to each other, create spaces for conversation about deep values, and in turn become enlivened by the intimacy of relationship, then a soul-force can emerge – the courage to do things that could not even be contemplated alone.

Furthermore, and to complexify the ideas a little more, if people in communities are animated by the idea of social justice, then they are likely to act in a way that puts pressure on the social state (or what is left of it) for their fair share of its resources. However, if people are animated by the idea of ‘taking responsibility’ or ‘enhancing resilience’, then a different kind of energy will emerge, focused on different actors (more likely to be the ‘self’, or the ‘group’). Hence language and discourse in turn shapes the energies available and the direction of action those energies are funnelled towards.

Taking these ideas of energy, field and force a little further, for the likes of Hillman, the self is self-ing, as verb. It is also true of our soul – it is soul-ing, made by what we inhabit and are inhabited by. For example, if people are inhabited by, and in turn inhabit, economic and consumerist values, focused on accumulating wealth and incurring debt, then the soul becomes solidified by those repeated patterns of wealth production (usually requiring use of all intellectual and creative energies at a colonising workplace). The soul – as animating energies – becomes literally colonised by work, with little left for community life. For many this is the case, and soul, as the body’s gravity, then leans towards anxious, accumulating, grasping and depressive states. However, if soul can be re-made by people’s immersion in new mental frames and habits, and exposure to artistic, relational, literary and philosophical endeavours that decolonise minds and bodies, then energies and desires can be discerned that are community and life oriented, and focused on new forms of resistance (to ‘development’) and action.

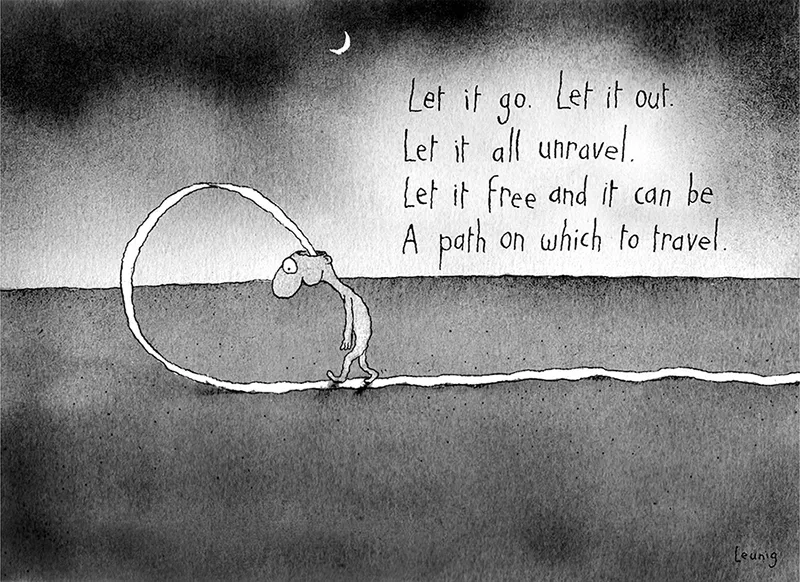

Crucial to this way of thinking about soul is to let go of any essentialist notion of soul that represents a core of who we might be, or the core of what community work is. A soul perspective on community practice is not a call to return to some essence (which is a very strong tradition of thinking within some writing about soul). This is a potentially serious danger, allied to histories of practice that seek unity, wholeness, and ‘a clear and certain way’ (think again of Hitler and the volk, of dangerous forms of patriotism such as getting behind ‘Team Australia’). Instead, soul is understood through the lens of force and field, as energies generated, constructed or shaped by a whole range of discursive, material, and emotional elements. The practice is to be attentive to these energies, and the forces and fields generating them; and to then be agile and responsive in working with, around, beneath or against them.

Avoiding Definition of Soul, while Providing Signposts

Within this chapter some settings and signposts of how I have come to understand a soul perspective in relation to community work are offered. However, definition is avoided. There is not an attempt to build a unified theory of soul in community practice – hence the notion of settings and signposts (perhaps pointing in somewhat different directions) and also the diverse dialogues that sit at the heart of the text. As Hillman asserts, ‘soul is ceaselessly talking about itself in ever-recurring motifs in ever-new variations, like music; that this soul is immeasurably deep and can only be illuminated by insights, flashes in a vast cavern of incomprehension’ (Hillman, 1977: xxii). Soul is polytheistic, multiple, and this simple assertion foregrounds the multiple energies that are at play in any community process – thankfully. Avoidance of the single narrative, the collective groupthink, the volk, the certainty of analysis is crucial within soul-work.

With these thoughts in mind, and recognising that a genealogy of the ancient concept of soul would require a book in itself, the rest of this chapter offers a few further thoughts, firstly by drawing on how the existing community work literature has previously used the concept of soul, and then secondly as a signposting of some of the other ways I intend to use it in dialogue with the other authors.

Soul and Community Work Literature

It was intriguing to sit down one day in 2014 and conduct a systematic search and review of how the existing community work literature uses the idea of soul. Not surprisingly, the search and reviewing process didn’t take long – only a tiny handful of community work or development journal articles use the concept of soul. And even then only mostly within throw-away lines where the concept is not discussed or defined in any particular way. For example, some authors use the concept in relation to community or associated spheres, referring to, ‘a community with a soul’ (Du Sautoy, n.d: 149), or ‘housing estates [which] have a character, a soul’ (Vasoo, 1984: 12), or even ‘the soul of civil society’ (Shaw, in Carpenter and Miller, 2011: iv). The reader cannot be sure what is meant by the use of soul in these sentences, but they do seem to tap into those metaphoric and mythic dimensions, that sense that the meaning is related to life, character, vitality, essence even.

Other authors talk about soul in relation to the community development profession or program. Paul Bunyan argues, in reference to the UK community development profession and the context of co-option under neoliberal regimes, that it is ‘at risk of losing its identity and soul’ (Bunyan, 2010: 115). In a similar way Meher Nanavatty, commenting on India’s earlier experiments with community development, states that, ‘the programme of rural community development in India has declined, maintaining its administrative structure physically but losing its spirit, ideology and the very soul-force which sustained it in early years’ (Nanavatty, 1988: 96). In a delightful, if not somewhat ambiguous sentence, Ed Gondolf, reflecting on the use of community development within a war torn Guatemala argues that,

Without this faith in the potential animus of community development, the tide of violence is likely to destroy, if not scare away altogether, CD proponents. A commitment to cooperation, participation, self-reliance, self-determination – concomitants of the soul, as well as ideals of the spirit – do have a transforming power. Therefore, community development when infused with a commitment of the soul, can and should act as a countering, non-violent, political force to oppression and violence. (1981: 236)

An inspiring couple of sentences, and my reading of it is that soul represents for him, much like Nanavatty’s thoughts on India’s experience, and Bunyan’s on the UK’s, the animating energy within community or community development.

Departing from this use of soul, a few commentators use the idea of soul in the context of re-thinking development as a holistic endeavour. For example, Love Chile’s work, drawn from the New Zealand experience, argues that for most Maori people, ‘development as a holistic process does not divide body, mind and soul, the physical from the non-physical, the individual from the group’ (Chile, 2006: 423). He expands that ‘Maori spirituality evolved from the belief in an essential connection between humanity, the natural world and the universe. This is an indivisible relationship derived from Mauri, the universal soul, life-force and energy’ (Chile and Simpson, 2004: 326). At the core of Chile’s writing is the notion of undoing the bifurcations of body, mind, spirit and soul along with the dualism of individual and collective, inviting a more holistic viewpoint with implications for practice. It’s an important contribution, and a viewpoint shared wholeheartedly by myself.

Moving from New Zealand to the USA, the author who has most clearly and explicitly drawn on the concept of soul in relation to community development is previous president of the USA based Community Development Society, Ronald Hustedde. He has written two relevant papers, the first being a 2002 piece on ‘Rituals, emotion, community faith in soul and the messiness of life’ (Hustedde and King, 2002); and the second, initially a keynote address at a Society conference, titled, ‘On the Soul of Community Development’ (Hustedde, 1998), which was later turned into a journal article. In that paper he explores three major questions: (i) what is soul? (ii) why do we need to discuss and nurture it? and (iii) how do we integrate soul into community development?

In relation to the first question his main contribution is the assertion that ‘Soul is the existence of some kind of animating presence within humans and other living things’ (ibid.: 154). He goes onto argue, drawing on more popular authors, that ‘soul is expressed through beauty and art. It is about deep meaning and quality relationships. Soul thrives on paradox. It is about mystery … Metaphor and simile are used to describe soul, which is non-linear and can be expressed through soulful or spiritual acts’ (ibid.). While agreeing with his assertions, the potential danger in this viewpoint is to think of the animating energy as a force, rather than also as a field shaped by numerous elements (discursive, physical, social, economic).

In relation to the second question Hustedde makes a case for thinking about community development in terms of a ‘tripod’ of mind, body and soul. In this sense ‘in community development, the mind is the intellectual dimension’ (ibid.), evidenced in research, case studies, and so forth, and the body of community development ‘is expressed … in several ways, as about organisational structure; community action; and meeting basic human needs’ (ibid.: 155). He also argues that ‘the body can be dysfunctional when not balanced by soul’ (ibid.). Recognising the metaphoric play at work here, and therefore not disagreeing profoundly, I simply depart in perspective at this point, arguing much like Chile above, that holding a more integrated holistic approach could be more helpful. Within my framing of soul as animated energies I think of the body, ...