The pre-modern era

Accepting Islam as a new religion in the sixth century brought many changes to different parts of Iranian social and economic life, including urbanisation. In comparison to the pre-Islamic era, the importance of religion and religious organisations in urban society brought about the most important change in this era. The mosque as a place for worship and Muslims’ social life became a main element in the social structure of cities. The mosques in Islamic cities that were found in most suitable places of the city and next to main government buildings and bazaars provided functions such as producing and publishing religious knowledge and informing and gathering news (Lapidus, 1984).

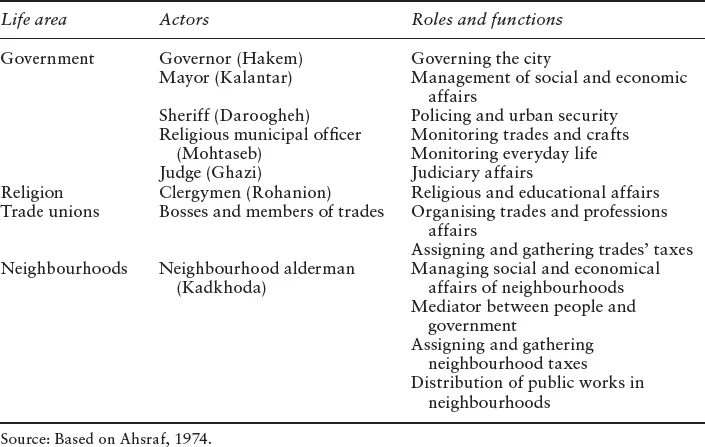

Ahmad Ashraf (1974: 24) divided Islamic urban life into four areas: government, religion, trade unions and city neighbourhoods. Different roles and functions in those areas can be seen in Table 1.1.

Besides its political authority, urban government had three sections:

Table 1.1 Areas of urban life in the pre-modern era

The governor (Hakem) and mayor (Kalantar) were responsible for section A; judges (Ghazi), for section B; and sheriffs (Daroogheh) and religious municipal officers (Mohtasseb), for section C. The top central government officials appointed all urban government officials. The king (Shah) appointed the governor who in turn appointed other city officials (Madanipoor, 2002).

One of the main features of Islamic cities was the emergence of trade unions (Asnaf) in urban life. In contrast with European trade unions or guilds, they had broader social functions like close relations with religious institutions and landlords. Guilds had more economical power and more supervision over professional affairs. The heads of guilds were chosen by their members, but the heads of Islamic trade unions were chosen by the governor and through the agreement of members. Trade unions in Islamic cities were responsible for gathering tax and price fixation. On behalf of the governor, they had financial and administrational duties.

The neighbourhood (Mahaleh) was the fourth area in urban life in the Islamic era. According to Sheikhi (2003), urban life was basically organised into neighbourhoods, and the city revolved around a neighbourhood system. Ethnic, racial, religious and professional groups lived in separate neighbourhoods. Sometimes every neighbourhood was a semi-independent town within the city with its own mosques, bakeries, small bazaars, cisterns and public baths (Hammam). Therefore it was not necessary for many inhabitants to go out of their physical neighbourhood environment. Neighbourhood bonding was intensified by ethnic, religious and professional similarity. Every neighbourhood was a bounded and separate group for its members, and other neighbourhoods were alien groups. Conflicts between neighbourhoods were the main reason behind urban conflicts due to strong internal solidarity between members and dissociation and segregation from other neighbourhoods. This was a characteristic that set Iranian cities apart from Europeans ones.

Max Weber (1966) identifies the medieval city with these features:

powerful trading relations

castel and fortification

bazaar

a court and semi-independent authority

association and cooperation

semi-independency and political authority

The main differences between European and Asian cities were political autonomy and citizen associations. According to Weber, the European city was a political organisation, but the Asian city constituted a tribal city. Neighbourhood life was based on differentiation between ethnic, religious and social groups rarely allowed to establish a social identity based on the city (Hourani et al., 1993). Forming social relations or bridging social capital outside of the neighbourhood community was not foreseen. Because bridging social capital relates and unifies different social groups, it is a factor that could increase citizens’ participation and their power against the government (Putnam, 2000; Paxton, 1999).

The people in power continued to rule their people and the city through intervention in conflicts among hostile neighbourhoods and gained the opportunity to be the unique reference for judgment and peace. In other words, their interests were based on hostility between neighbourhoods. However, they were not interfering in neighbourhoods’ internal affairs, and their main demands were local taxes.

The closed neighbourhood offered many functions for its inhabitants. The most important function was the security of the neighbourhood. There was a limitation on the coming and going of strangers, and the inhabitants of the neighbourhood could observe any odd and unusual behaviour. Despite economical, political and social differences between social strata, there was a relative homogeneity and conformity among inhabitants because of the simplicity of life, cultural harmony and close proximity of place. ‘The spatial separation between rich and poor neighbourhoods was low and different people, both rich and poor, clergymen, businessmen and tradesman lived in all city neighbourhoods’ (Ashraf, 1982: 84). This feature added to the homogeneity of neighbourhoods as the inhabitants of the neighbourhood had mutual relations in many public spaces such as the public baths, the mosque, the neighbourhood market (Bazarcheh) and alleys.

Islamic cities did not have political autonomy and were dependent on the king’s city agent, namely the governor (Hakem). As mentioned before, the king appointed the governor, but he could not exercise a direct and immediate authority. The governor appointed a mediator, known as Kalantar, for his dominance and communication with the people. He was one of the city authorities under the direct command of the governor who played a mediatory role between the people and the city government. So we cannot say he was the representative of independent urban interests of the people. Although the Kalantar’s position was dependent on the governor, he could gain more power when central government power was decreased by anarchy and disorder. He took power and sometimes declared autonomy (Ashraf, 1974). The governor often appointed more than one Kalantar for managing public affairs in big cities.

The Kalantar was also an inheritable position and belonged to famous and respected families of the city. He must have had legitimacy and social acceptance and be trusted by the people; otherwise, he could not exercise his duties. The main responsibility of the Kalantar was to assign a tax quota for every trade union through cooperation with its aldermen. He tried to distribute heavy work equally, such as repairing water storage facilities and mosques, between all taxpayers with nobody being overcharged. Meanwhile, he sought to gather taxes and tariffs. The Kalantar issued certificates of craftsmanship and orders of appointing trade aldermen and neighbourhood aldermen.

Citizens were the final group who were responsible for managing neighbourhoods. Neighbourhood inhabitants did not have the right to choose their neighbourhood alderman. It was not an elective process because the Kalantar had the right to choose the Kadkhoda or neighbourhood alderman. Nevertheless, the Kalantar usually appointed the Kadkhoda from respected and well-known families. The governor and mayor consulted with neighbourhood aldermen on the subject of taxation because of the aldermen’s familiarity with neighbourhood people. Aldermen tried to distribute the neighbourhood’s tax or other expenditures between inhabitants. He distributed public works and was the mediator between neighbourhood people and local authorities (Ibid). ‘Despite the fact that his position was recognized by city officials as a formal one, he did not receive a salary and did his job as a volunteer. This position often was inheritable and remained in a family for a long time’ (Soltanazadeh, 1988: 212).

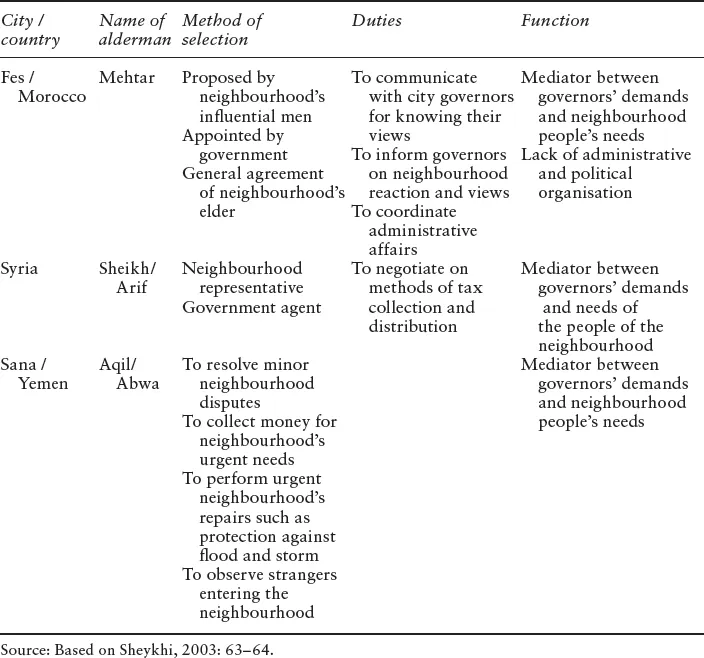

The alderman had a dual role. One part of his job was managing the neighbourhood’s public affairs; the second part was acting as a representative of city government for the neighbourhood people. These two roles occasionally conflicted with each other, especially when the alderman was protecting the people’s interests and at the same time watching and collecting taxes requested by the government. Therefore, being a neighbourhood alderman was not an easy task, and it necessitated experience, knowledge and social acceptance amongst people and authorities. It seems all cities in Islamic territories used the alderman mechanism for managing neighbourhoods. In his article on the neighbourhood structure of the city in the Islamic period, Sheikhi (1382) mentioned some examples of this mechanism in different cities, of which an abstract is shown in Table 1.2.

There were two ways of providing for common neighbourhood needs, such as public building and spaces. First, people participated in raising funds and in the workforce. Second, elders and rich citizens of the neighbourhood provided the money for the construction of public buildings. ‘In this situation the person who was the builder of a building or complex, if it was possible, assigned the revenues of an endowed property for future expenditures’ (Soltanzadeh, ibid: 249).

Table 1.2 Neighbourhood management in the pre-modern era of Islamic world

The Kadkhoda did not have an absolute authority in the neighbourhood. His authority was influenced by other powerful people, such as the governor, the imam of Friday’s prayer (Imam Jomeh), great clergymen (Sheykh ol Islam), sheriffs, water distributers (Mir aab), religious municipal officers (Mohtasseb), chiefs of tribes, and rich businessmen.

We must consider the rogues (loti) as the people who influenced the neighbourhood and its affairs. They handled sports club (Zoorkhane) or were brokers in bazaars, managed the Moharam month mourning ceremonies, patrolled the streets and were the guards of neighbourhood bounds.

(Abrahameeyan, 1999: 30)

Nevertheless, some rogues were a threat for their own and surrounding neighbourhoods as they committed crimes such as robbery and homicide.

It seems there was no participatory institution for citizen participation in this era. Although there were semi-democratic mechanisms, such as neighbourhood aldermen and electing people who the locals accepted, they could hardly act like modern democratic organisations such as city and neighbourhood councils. The main features of urban management were

Officers were appointed by the governor not by people.

Officers did not have democratic legitimacy.

Family status and reputation for appointing the officers were important.

It lacked any accountability and responsibility mechanisms.

One of the main changes in city government was the establishment of Ehtesabeeye, or the municipality, in the Naser al-Din Shah era after his journey to Europe in the nineteenth century. It could have been an opportunity for public participation because of its potential capacity for electing councillors and a mayor, but the new organisation had a limited function – only to take care of street cleaning and lighting around the king’s palace (Najmi, 1990). It was not for developing participation and urban democracy. The king appointed Mirza Abbas Khan Mohandes Bashi who was educated in France as the head of the new Ehtesabeeye department. The main duties of the new department were to manage trade unions’ affairs, to look after city’s public affairs, to supervise citizens’ behaviour and their allegiance to local governors. The city governor put the everyday affairs and executive works in the care of the Kalantar who was the head of Ehtesabeeye. Ehtesabeeye had three departments for works such as street cleaning, garbage collection and lighting in Tehran. It had about one hundred mules and donkeys for taking out garbage and some water carriers (Sagha) for spraying water on the streets. The main area of its work was around the king’s palaces and government buildings. It belonged to the state and received its financial resources from it. The citizen had to pay no local charges, such as taxes, for running the city government. The Shah appointed its officials, and they were dependent to him. Urban management did not have features such as an elective body, decentralisation and dependency on people’s voting (Hareesinejad, 2010). Ehtesabeeye was merged to become a new police organisation later, and a new department was established as ‘the great capital po...