- 548 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Music and Identity Politics

About this book

This volume brings together for the first time book chapters, articles and position pieces from the debates on music and identity, which seek to answer classic questions such as: how has music shaped the ways in which we understand our identities and those of others? In what ways has scholarly writing about music dealt with identity politics since the Second World War? Both classic and more recent contributions are included, as well as material on related issues such as music's role as a resource in making and performing identities and music scholarship's ambivalent relationship with scholarly activism and identity politics. The essays approach the music-identity relationship from a wide range of methodological perspectives, ranging from critical historiography and archival studies, psychoanalysis, gender and sexuality studies, to ethnography and anthropology, and social and cultural theories drawn from sociology; and from continental philosophy and Marxist theories of class to a range of globalization theories. The collection draws on the work of Anglophone scholars from all over the globe, and deals with a wide range of musics and cultures, from the Americas, Australasia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. This unique collection of key texts, which deal not just with questions of gender, sexuality and race, but also with other socially-mediated identities such as social class, disability, national identity and accounts and analyses of inter-group encounters, is an invaluable resource for music scholars and researchers and those working in any discipline that deals with identity or identity politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Music and Identity Politics by Ian Biddle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Etnomusicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Gender and Sexuality

[1]

Sic ego te dilegebam: Music, Homoeroticism, and the Sacred in Early Modern Europe1

Modern readers of the motet Planxit autem David face a musical text rich with challenges.2 One of a handful of Renaissance motets to set David’s lament on the death of Saul and Jonathan,3 it was attributed to Josquin by Heinrich Glarean on the basis of its rhetorical virtuosity.4 If that attribution is problematic,5 Glarean’s assessment of the music was accurate: the motet stands apart from other motets by Josquin, indeed, from other motets appearing around 1500, in its highly rhetorical treatment of the text.6 The rhetoric of the music is more than matched by that of the text itself. The lament is a brilliant speech in which the young warrior-musician publicly declared his respect for the fallen king of Israel and thus ensured his rise to the kingship of Israel. But the lament is even more notorious for David’s forthright declaration of love for Jonathan, a declaration that has struck readers, both ancient and modern, as markedly homoerotic. Perhaps the central challenge raised by Planxit autem David, quite apart from the issue of authorship, is understanding how it negotiates the tensions between the sacred and secular worlds, and how it conflates the erotic and the divine.

This chapter approaches Planxit autem David as the only substantial reading of an important biblical text that was largely overlooked by the medieval and early modern church. While the patristic and exegetical literature is rife with expositions on David the king, the warrior, the musician, and lover of women, and while artists and sculptors and illuminators took up these same themes in their work, only this motet addressed the text with a rhetorical intensity that reveals how the lament was understood in the Renaissance.7 Planxit autem David participated in a homoerotic discourse common in Renaissance sacred culture. This discourse, often carried out (as was so much of Renaissance discourse) in a language of metaphor and allusion, drew not only upon cultural constructs of homosexuality inherited from antiquity, but also upon the homosocial and often homoerotic nature of music itself.8 Planxit autem David, then, represents an combination of theological, humanist, and musical epistemologies that has gone largely unnoted by modern scholars of early music. By reading this motet as a location for the intersection of eroticism and religion, it also can be read as a locus of the intersection of music and the homoerotic. The intent is not so much to “queer the Renaissance” as it is to propose a fuller view of the complicated and rich nature of sacred music and early modern religion.

Early modern listeners of Planxit autem David heard the piece through several filters, including the historical context of the Biblical narrative, and the contemporary context that valorized same-sex erotic dynamics. David’s performance of the lament is the final episode of his history in the house of Saul, which is largely exposed in I Samuel. (The text of the lament, which appears in II Samuel 1: 17–27, is given in the Appendix). Saul, the ruler of the Israelites, and his son Jonathan, were engaged in war with the Philistines. Distressed by evil spirits, Saul summoned David, “a musician, a warrior, skilled in speech, and handsome.” From the moment of David’s arrival Saul “loved him so much that [David] became his weapon bearer,” and David’s musical performances successfully exorcised Saul’s demons (I Samuel 16:16–23). As a leader of Saul’s army, David soon met with success as a warrior, defeating the Philistines, but incurring the envious wrath of Saul, whose demons returned. In his jealousy, Saul plotted against David’s life, causing David to leave the Israelite camp and enter into temporary exile with the Philistines. Without his chief warrior, threatened by the Philistines, and deprived of David’s music, Saul succumbed to demonic influence, consulted the witch of Endor, fell out of favor with God, and, as a result, died on the battlefield. David’s relationship with Jonathan was no less intense. By the time David had finished introducing himself to Saul, Jonathan “had become as fond of David as if his life depended on him; he loved him as he loved himself.”9 Indeed, Jonathan became David’s champion, turning aside Saul’s jealous rage on several occasions, and helping David to escape Saul’s homicidal plots (see, for example, I Samuel 19). More, the great love between David and Jonathan fed Saul’s jealousy, who saw in it the frustration of his dynastic designs.10 Jonathan, heir apparent, came to David and said “Have no fear, my father Saul shall not lay a hand on you. You shall be King of Israel and I shall be second to you. Even my father Saul knows this” (I Samuel 23: 16–18). Jonathan, however, falls with Saul in battle, and on hearing this news, David uttered his lament before the Israelites.

The obvious political exigency served by the lament was to remove any suspicion of complicity on David’s part in the death of Saul.11 But more than this, the lament provided David with a forum in which to declare his love for Jonathan, and his remark that his love for Jonathan surpassed the love for women (II Samuel 1: 26) is remarkable for its intensity. The unmasked homoeroticism of that love must account for the silence of the church fathers and later medieval exegetes on the topic.12 Indeed, the medieval church displayed a certain amount of anxiety about this verse when, in the process of redacting the Bible during the middle ages, it added the phrase “sicut mater amat filium suum sic ego te diligebam” to the penultimate verse of the lament.13 The late fifteenth-century readers of the Vulgate, then, read at II Samuel 1:26 “I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan; very pleasing have you been to me; your love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women. As a mother loves her son, so have I loved you.” However, references to David’s homosexuality throughout the middle ages and the Renaissance attest to the fact that this facile emendation did little to prevent readers of the text from recognizing the intensity of emotion between David and Jonathan.14

It seems likely that on some level the love of David and Jonathan was understood as homosexual in a sacred culture where the metaphor of physical union of a male believer with the male divinity was developed through allusions to sodomy, penetration, and the eroticized body. This was to be expected from a culture active in reconciling the epistemologies of Christianity and pagan antiquity,15 and in which homosexuality, because of its classical credentials (not to mention contemporary actuality), was an unavoidable topic.16 Negotiating these tensions, the great Florentine neoplatonist Marcilio Ficino (1433–1499) found echoes of Christian ideals in Platonic philosophy.17 Against the backdrop of a sacred tradition that officially denounced homosexuality,18 Ficino, in his widely read commentary on Plato’s Symposium on Love, expounded on the Platonic concept of eros begetting knowledge in order to develop a philosophy of intense Christian love that, eschewing physical consummation, channeled the intensity of erotic attraction toward sacred goals.19 In a similar way, artists and poets drew homoerotic themes into their work, so that sodomy could stand in for salvation in the poetry of Dante, Christ’s penis became for Renaissance artists a symbol of the potency of the resurrection, and his lacerated body the focus of an intensely erotic male gaze in English devotional poetry.20 In the other direction, classical mythology dealing with homosexuality was subsumed into Christian theology. The most widespread instance of this phenomenon dealt with the rape of Ganymede, in which Jupiter took the young boy to be his cupbearer and sexual companion. This myth was widely interpreted by the Renaissance as a symbol of the Christian soul taken to heaven in a mystical union with the divine.21

The biblical narrative of the love between David and Jonathan, and of the lament in particular, resonates with these other manifestations of the erotic and the divine. David’s authority as a figure of the past is obvious, but because this lament marks the moment of David’s ascent to the throne of Israel—to his founding of a hereditary line that culminated in the birth of Christ—it, in a sense, marks a liminal moment in which David became divine, thus enhancing his authority.22 As in other homoerotic artifacts of antiquity, the energy of David’s eros lay just beneath the surface. Just as the Ganymede myth could be understood, if incompletely, as having to do with cup bearing by attending to those authors who ignored or denied the sexual element of that narrative, the Davidic history could be, indeed often was, told without reference to his homosexuality. But if artists and commentators could, as they did, tap into the transuming rapture of Ganymede and Jupiter, if the practice of sodomy by ancient Greeks could be reconfigured as Christian love by neoplatonic philosophy, if Christ’s sexuality could be tapped for morally uplifting ends, then David and Jonathan too were situated to be similarly exploited by Christian humanists.

It is here that Planxit autem David becomes important, for it is a persuasive reading of the Davidic history that takes into account, more, focuses upon, the eroticism of David’s love for Jonathan. Planxit autem David abounds with rhetorical detail So dense and focused is the composer’s attention to the text that one understands well Glarean’s effusive praise:

… throughout this entire song there has been preserved the mood appropriate to the mourner, who at first is wont to cry out frequently, and then, turning gradually to melancholy complaints, to murmur subduedly and presently to subside, and sometimes, when emotion breaks forth anew, to raise his voice again and to emit a cry; all these things we see observed very beautifully in this song, just as it is also apparent to the observing. Nor is there anything in this song that is not worthy of its composer. He has everywhere expressed most wonderfully the mood of lamenting, as immediately after the beginning of the tenor, at the word “Jonathan.”23

While it is unclear exactly to which passage Glarean refers (the word “Jonathan” appears four times in the lament), he may well have pointed out that everywhere in this motet is expressed a wonderful sense of focus on Jonathan. For everywhere in the lament that Jonathan is named, directly or indirectly, the text is marked with melismas, harmonic inflections, or changes in texture. And although on the surface these gestures can be read as mournful, there is (as is so often the case in Renaissance poetry) pleasure in this pain.

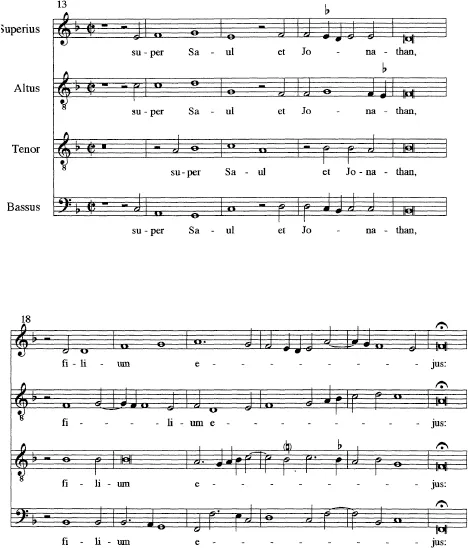

The first appearance of Jonathan, in mm. 16–17, which is marked by a harmonic shift to a cadence on B-flat followed immediately followed by an effusive melisma on the text “filium ejus” in mm. 18–23, exemplifies this rhetorical focus. Whether the melisma is heard as mournful lament or pleasurable recollection, the concentration of rich musical expression at the first reference to Jonathan stands in stark contrast to the somber, homophonic, syllabic declamation of Saul’s name in mm. 14–15. The passage reveals, from the outset of the motet, the emotion and pleasure, that David associated with Jonathan (see Figure 9.1). This display of pleasure at references to Jonathan occurs again and again whenever Saul and his son are mentioned in the same breath. In the tertia pars of the motet, for example, at the text “Saul et Jonathan amabiles …” (verse 23, mm. 195–198), “Saul” is again declaimed syllabically, while the use of melisma on “Jonathan,” directs the listener to connect pleasure with the fallen prince.

Most central to my reading of this motet is the musical treatment of David’s forthright declaration of love for Jonathan in verse 26. It is here that David’s love for Jonathan is revealed, here that David fully enters into the homoerotic epistemology of the Renaissance, and the musical rhetoric of Planxit autem David is wielded with the most virtuosity. This, the quarta pars of the motet, begins with a solemn homophonic statement of the text “Doleo super te,” followed by pai...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I GENDER AND SEXUALITY

- PART II RACE

- PART III SOCIAL IDENTITIES

- Name Index