eBook - ePub

Predicting Religion

Christian, Secular and Alternative Futures

- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Predicting Religion

Christian, Secular and Alternative Futures

About this book

Religion in the contemporary west is undergoing rapid change. In Predicting Religion twenty experts in the study of religion present their predictions about the future of religion in the 21st century - predictions based on careful analysis of the contemporary religious scene from traditional forms of Christianity to new spiritualities. The range of predictions is broad. A number predict further secularization - with religion in the west seen as being in a state of terminal decline. Others question this approach and suggest that we are witnessing not decline but transformation understood in different ways: a shift from theism to pantheism, from outer to inner authority, from God to self-as-god, and above all from religion to spirituality. This accessible book on the contemporary religious scene offers students and scholars of the sociology of religion and theology, as well as interested general readers, fresh insights into the future of religion and spirituality in the west. Published in association with the British Sociological Association Study of Religion group, in the Ashgate Religion and Theology in Interdisciplinary Perspective series.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Predicting Religion by Grace Davie,Paul Heelas,Linda Woodhead in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

ReligionIII

Predicting Alternatives

Chapter 11

The Self as the Basis of Religious Faith: Spirituality of Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Christians

Andrew K. T. Yip

Introduction

Sociologists of religion do not speak with one voice regarding the social position of religion (specifically Christianity) in late modern society. Some (for example, Bruce, 2001; 2002), using official statistics which indicate dwindling church attendance, argue that religious beliefs and practice are in decline. Others (such as Davie, 1994; 2000a) argue that the decline of religious affiliation need not imply the decline of religious beliefs in the population at large. Religious beliefs, Davie argues, could be independent of religious practice, defined, say, in terms of church attendance (for a detailed discussion of this, see Davie, 2000b; 2002). I am inclined to support Davie's view: non-affiliation to institutionalized churches and the decline of religious practice within this context should not be equated with 'despiritualization'. Some believers might not define themselves as 'religious' in the traditional sense, but this does not mean that a 'spiritual' dimension is absent from their lives. Even for those who consider themselves 'religious', the construction of their religious faith and identity takes on a more personal dimension. And this characteristic of individual religious orientation reflects the construction of personal identities in late modern society in general, on which this chapter focuses.

Giddens has argued that late modern society is a world of traditions, but not a traditional world. This denotes that, while traditions and institutions still exist in their transformed form, their scope and extent of influence in the lives of individuals are decreasing. In turn, life in late modernity has become increasingly internally referential and reflexively organised. While traditions are still in existence and continue to provide the overarching but fragmented framework for social behaviour, the individual increasingly relies on the assessment of the self for life choices and decisions. In other words, the self, rather than traditions, has become the ultimate point of reference in the individual's life course (for example, Giddens, 1991; 1999; Giddens and Pierson, 1998). This process of 'detraditionalization', as Heelas (1996) has argued, 'involves a shift of authority: from "without" to "within"... "Voice" is displaced from established sources, coming to rest with the self (p.2). Accordingly, traditions are increasingly losing their scope and influence on the individual's life, and in turn, the individual's self becomes increasingly dominant in the fashioning of her/his life. The self, with its assessment of and reflection on increasing options and risks, functions as the primary basis for the construction of identities.

The process of detraditionalization, it should be emphasized, by no means necessarily involves the total disappearance of traditions (if that were possible) and the complete reign of the self in the construction and management of individual and social life (if that were possible). I subscribe to the 'coexistence thesis', espoused by Heelas (1996), which argues that the self (that is, agency) and traditions (that is, structures) coexist and intermingle inextricably, albeit with varying emphases, in the construction and operation of social life. (For a good discussion of 'detraditionalization' and the 'coexistence thesis', see Heelas 1996.) What is salient for this chapter, though, is that within the late modern context, the self (agency) seems to have the upper hand in this complex process of construction. In the case of individual religious orientation in late modern society, there is no doubt that the individual is more inclined 'to locate God within, where spiritual agency can enhance true "human" authority' (Heelas, 1994, p. 105).

Within this conceptual framework, this chapter specifically examines the religious orientations of gay, lesbian and bisexual Christians in the UK. In the past two decades, this sexual and religious minority has been much embroiled in ideological and theological debates, some of which were widely publicized (for more details, see, for instance, Yip, 1997a; 1997b; 1999a; 1999b). The chapter will present research evidence which suggests that the self plays a far greater role than church authority as the basis of the respondents' Christian faith. This is heightened by the fact that their sexuality is 'problematic' to the churches, thus facilitating a process of reflexivity and self-evaluation. This leads to their learning to trust their personal experiences in positioning themselves in relation to a potentially stigmatizing institution. In fact, their continued affiliation to the churches much rest on their ability to distance themselves psychologically, or even to challenge the churches, on the basis of positive personal lived experiences. This is particularly true in relation to their sexualities (for example, being in a committed and long-standing relationship that upholds perceived Christian values such as love and faithfulness).

The Research Project

The data are drawn from a national survey of 565 self-defined non-heterosexual Christians, which was designed to examine a host of issues in relation to sexuality and spirituality. The project consisted of two stages. Stage 1 involved the collection of primarily quantitative data through the use of postal questionnaires (14 pages each) across the UK, between May and October 1997. Stage 2 involved semi-structured interviewing, between October 1997 and January 1998, of 61 respondents living in Scotland, Wales and every region of England. The majority of respondents were recruited through non-heterosexual groups/organizations whose members were either exclusively or predominantly Christian, such as the Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement.

The sample consisted of 389 gay men (68.8 per cent), 131 lesbians (23.2 per cent), 24 bisexual women, and 21 bisexual men (total 8.0 per cent). Their ages ranged from 18 to 76, with 297 (52.6 per cent) within the 31–50 category. Not surprisingly, the majority of respondents were affiliated to the Church of England (271, 48.0 per cent) and the Roman Catholic Church (149, 26.4 per cent). Other denominations included the Methodist (29, 5.1 per cent) and the Baptist (16, 2.8 per cent). As mentioned, this almost all-white (95.4 per cent) sample was scattered across the UK, with the majority living in Greater London (164, 29.0 per cent), the south east (74, 13.1 per cent) and the north west (64, 11.3 per cent) of England. In terms of occupation, the top three were clergy/chaplains (96, 23.9 per cent), teachers/lecturers (54, 13.5 per cent) and medical professionals (47, 11.7 per cent).

Religiosity and Spirituality

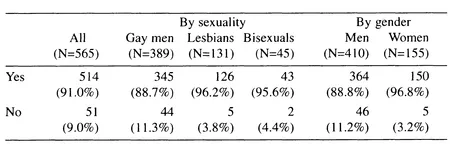

Table 11.1 shows that a vast majority of respondents (an overall 91 per cent) considered 'religiosity' different from 'spirituality'. Regardless of sexuality, over 88 per cent of respondents held this view. In terms of gender, a higher proportion of women (96.8 per cent) drew this line of demarcation, compared to their male counterparts (88.8 per cent). Qualitative data show that those in the 'No' category were inclined to view these terms as distinctive yet related, but not different.

Table 11.1 'Religiosity' is different from 'spirituality', by sexuality and gender

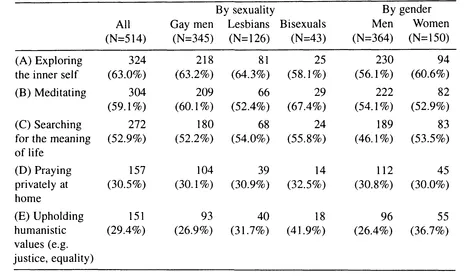

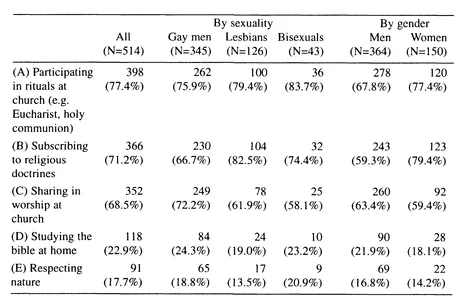

The 514 respondents in the 'Yes' category were asked to select from a list, of up to three statements, that best described their understanding of the terms. The results are presented in Tables 11.2 and 11.3.

Table 11.2 Top five statements that describe being 'spiritual', by sexuality and gender

Table 11.3 Top five statements that describe being 'religious', by sexuality and gender

The quotations below, extracted from questionnaires, further illustrate the distinction between the terms 'spiritual' and 'religious'.

Being spiritual is a way of being in the world, constantly asking the question 'Who am I?' in relation to myself, the world, and god. It is about journeying through life searching for myself and god. Being religious is about adhering to a rigid set of doctrines and participating in specific rituals. (Michelle, an Anglican lesbian from the East Midlands)

I understand being religious as attending church, observing and receiving sacraments and participating in the life of the parish. As a spiritual person I do none of these things, but participate more in a personal journey or exploration around faith and the meaning of life. (Michael, Catholic gay man from Northern Ireland)

The typical narratives below, drawn from interviews, further elaborate the differences they drew:

Spirituality is about being filled with the pureness, grandeur and earthiness of everything. You become in tune with absolutely everything, to the tiniest molecule. You are flooded with a sense of god's presence and energy. It is a fusion of both matter and spirit, creating a sense of oneness. It is deep within your soul. Being religious, that's like somebody going along with a set of rosary beads, going to a mass because it is an obligation, going to confession because the rule book says so. That's being religious: a set of obligations. Religion is a structured entity. You have got X, Y, Z, and if you don't follow this, you are out. There is a big chasm between the two. (Jim, a Pentecostal gay man, late 40s)

Religion is safe, spirituality is dangerous. Religion offers a clear view of how life should be lived. You could tick the boxes, and you are sound. That's what matters: in being sound. ... Spirituality is a journey, and it's not being scared of asking the questions and not receiving the answers, but actually it's part of it. The journey is in asking the questions, and there will be times when you have some understanding, but there is no guarantee. (Janet, a Baptist bisexual woman, late 30s)

On the whole, 'religiosity' seems to embrace two significant components: the adherence to doctrines and beliefs, propagated by the religious institution; and the observance of rituals and practices, within a communal religious context, 'Spirituality', on the other hand, denotes a self-based internal journey of experience with the divine. It is about the relationship between the individual and her/his faith, not necessarily mediated through the church. It is personal and experiential.

Quantitative data show that the majority of respondents argued that 'religiosity' and 'spirituality' are distinct. Qualitative data from questionnaires and interviews, on the other hand, suggest that the respondents, if asked to choose, would consider 'spirituality' rather than 'religiosity' as a more accurate description of their Christian faith. However, they also acknowledged that, in an ideal situation, the two should feed each other for a more wholesome and comprehensive Christian faith. Therefore these two terms are not completely independent of each other, as found in the study by Zinnbauer et al. (1997) and Marler and Hadaway (2002). The typical account below illustrates this:

Religion without spirituality is dead. Spirituality without religion tends to drift loose from its moorings as it were. I think it is too easily led astray. I think one needs not only the help and support, but also the structure of Christianity as a whole. This is where I think religion can be a helpful aspect of one's overall Christianity. But, I would say, if you have to choose between the two, then the inner reality is more important than the outward form. If religion proves to be a hindrance rather than a help to one's relationship with god, then I think it has to be questioned and, if necessary, jettisoned. I know some people who leave the church, temporarily or permanently. It is a barrier, rather than an aid, to their relationship with god. (Simon, an Anglican bisexual man in his 50s)

The primacy given to spirituality is telling. Most respondents appeared to place greater emphasis on the self rather than religious institutions and their perceived trappings. This is demonstrated even more clearly in the following section, where the basis of their Christian faith is examined specifically.

Basis of Christian Faith

In the questionnaire, the respondents were asked to rank, in order of importance, four items as the core components of their Christian faith. The results are presented in Tables 11,4 and 11.5. These tables demonstrate that there is a consis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- I SECULARIZATION THEORY RE-EXAMINED

- II PREDICTING CHRISTIANITY

- III PREDICTING ALTERNATIVES

- Index