![]()

PART Introduction

ONE

The book is in five parts. This first part contains just one chapter and provides some opening thoughts. I introduce some themes to be explored later.

Chapter 1 provides clues towards understanding some key ideas I shall use. These include

- strategic learning

- self managed learning.

In Part Two I shall define more precisely what I mean by strategy in the context of learning and in Part Three I shall discuss what I mean by 'good learning'. Self managed learning is introduced as an idea in Chapter 1 and elucidated more fully in Part Four. Part Five looks at some issues of practical application.

In this edition, I have added three appendices to provide some more concrete detail on issues raised in the text.

![]()

1 Introduction: some basics

The basic issues

René Fichant, the CEO of Michelin Tyre, once told a story which I shall modify here. Three men were shown a room with two doors. They were told that behind one door was wealth beyond their wildest dreams–gold, silver, priceless jewels. Behind the other door was a hungry man-eating tiger. They were each given the option of entering the room and opening a door. The first man refused the choice and left. The second man–a good strategic planner–hauled out his computer, analysed probability data, performed some risk analyses, plotted graphs, produced charts, created scenarios, and so on, and after much deliberation he opened a door and was eaten by a low-probability man-eating tiger. The third man (and, of course, the third one is always the winner) spent his time learning to tame tigers.

Learning in organizations makes sense. Indeed, organizations in which there is little learning, or the wrong kind of learning, do not survive in the modern world. Some, such as IBM, can survive a long time because of their size and monopolistic position. But even IBM's poor learning culture eventually caught up with it in the late 1980s.1

The trouble is that learning is not a very visible process. It is internal to people and often takes time. In a world that values the obvious, the immediate and the concrete, learning gets undervalued. Many organizations seem to have taken to heart the graffito I once saw which said '500 million lemmings can't be wrong.' And as they hurl themselves off the cliff shouting 'so far, so good' they take with them many innocents–into unemployment or impoverished jobs.

When I argue with top managers about the importance of learning–and the need to take a strategic view of it–I get a sense of how Kierkegaard felt in his dismay at how his words were received. As he said, he felt like a theatre manager who runs on stage to warn the audience of a fire. But they take his appearance to be part of the farce they are enjoying, and the more he shouts the louder they applaud. Of course, it is not applause that is required, but another kind of action.

The situation may be changing, however. My modification of the 'Law of Revolutionary Ideas'2 suggests that a new proposal goes through three stages of reaction:

- 'It's stupid and irrelevant–don't waste my time.'

- 'It's interesting, but not worth doing.'

- 'I said it was important all along.'

I believe many organizations are at stage 2, and a few are at stage 3. Although this comment is valid, it relates mainly to the English-speaking world. Japan is an example of a society that has taken learning extremely seriously for a long time, and its industries have reaped the benefits of its rapid learning.3

Learning levels

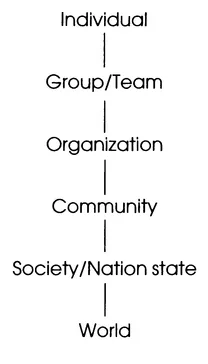

While this book has its main focus on organizational life, I want to draw attention to wider issues. There are various levels at which we can pay attention to learning. These can be delineated, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Levels of learning

While I believe that, strictly speaking, learning is done by individuals, there has been a growth of attention on 'learning organizations'. Usually this latter means creating a 'context for good learning' (and the latter will be explicitly addressed in Chapters 4 and 5). However, the other levels (that is, other than individual and organization) are also important. It's clear, for instance, that some work groups or teams seem rich in learning whereas others in the same organization are 'learning impoverished'. Also, particular communities within nation states seem to provide a better learning culture than others. In the UK, Wales and Scotland are significantly more learning oriented than the East End of London. Working-class children in Cardiff and Glasgow are much more likely to gain qualifications and to enter post-school education than equivalent children in London's East End.

Issues of learning are of major significance to us all –in all the roles we play–as individuals; as members of groups, organizations and communities; as citizens of our countries and of the world. If the emphasis on learning in organizations de-emphasizes these other levels, then this is an unbalanced focus. If, on the other hand, learning to make organizations better places within which to learn helps us to focus on other contexts as well, then it must be a good thing. (Wider aspects of 'good learning' are discussed in Chapters 4 and 5.)

Big picture and little picture

A famous 1960s writer, Baba Ram Dass, once said that when you're floating in inter-galactic ecstasy you need to remember your zip code. Somehow we have to hold together the big picture and the little picture. We have to integrate the visions for our organizations with day-to-day practice. Otherwise we have what we so often see in organizations: dead vision/mission statements devised through some detached bureaucratic process. They do not relate to people in their daily lives and hence become the butt of cynical banter from secretaries and shop-floor workers. ('Have you seen the latest nonsense to come from the top floor?')

Case examples

I would like to introduce a few cases of learning-based approaches that address these and other problems, and this chapter will show some concrete examples that link the big picture and the little picture. They will provide a basis for what is to come in later chapters, and I shall signpost references for the reader who wants to leap ahead–or at least to know what follows the 'hors d'oeuvre'. This hors d'oeuvre provides small tasters of what follows–but please do not confuse it with the main meal.

At the core of this chapter are the outlines of two cases of strategic learning. The cases throw up a range of issues, a few of which will be addressed in this chapter. The remainder will emerge as the book progresses. I want to start with concrete examples so that the ideas and discussion that follow are grounded in real-life issues.

The two cases are presented fairly baldly. At first sight the aims of the programmes and the claims for their efficacy may seem familiar. After all, everyone in the business of promoting organizational learning claims that what they are doing is good. I hope in later chapters to demonstrate that there is genuinely something different, special and especially excellent about strategic learning and about the self managed learning method as part of this approach.

The active reader

You will find examples of models, checklists, and other materials used in strategic learning approaches scattered through the text. I would encourage you to test them. Like clothes bought off the rail, they may not fit, but you'll only know this for certain by trying them on. And the process of 'trying them on' may help you to see what else you could use. Also, this kind of process is consonant with the self managed learning mode of operating that I shall emphasize in this book.

Strategic learning in a drinks business

The first case presented here concerns the Wines and Spirits Division of Allied Domecq. The work started when the division was called the Hiram Walker group and was part of Allied-Lyons (before the company took on the Domecq business and changed its name).

The company distributes a wide range of wines and spirits (for example, Courvoisier brandy and Beefeater gin). The group was formed from a merger of well-established companies, and in its merger saw the need for significant change. Top management wanted to move the culture from the cosy, patriarchal model that had been common in the drinks business towards a faster-moving, more entre-preneurial culture. They also knew that they needed to change strategically to operate in a highly competitive marketplace. With increasingly sophisticated approaches to purchasing, especially from the large retail groups, they needed to develop highly capable managers to operate in these new environments. (Chapters 2 and 3 discuss the wider aspects of the environments and markets in which organizations operate.)

They decided that their entire management team needed extensive and coordinated development if the business was to compete effectively. However, the history of the companies that had merged into the new organization was one of fragmented management development. Also, the whole personnel/human resources (HR) function had had an 'industrial relations' attitude, rather than a developmental one.

When I was asked to talk with their human resources development director they had already decided that they wanted a management development approach that would put all their senior managers through a significant learning process over approximately a three-year period. They were also clear that they wanted something that responded to individual needs. I and my colleagues worked with them in designing a self managed learning programme that would take about 60 to 70 managers initially, expanding to cover all their senior people in the three-year timescale

Initiating the programme

The first step was getting the buy-in of top management (at chairman and board level) to a process that was going to meet their strategic needs but would not look anything like a traditional management training course.

The company wanted to develop a culture that supported learning and change. Within this it realized that managers needed to take responsibility for their own learning, while the company needed to accept its responsibility to support managers in their learning. The self managed learning approach appealed because it met those needs and also allowed managers to work on job-related issues, hence overcoming transfer of learning problems.

The first stage was to put specific proposals to the board of the company, within the group, that handled the spirits business. They were to be the first part of the group to adopt the new approach.

The board recognized that they themselves needed to model this new approach. They had to give overt purposive support to the change, and they needed to learn better how to mentor and coach their senior managers (hence modelling a key aspect of the new culture). Therefore, in parallel with developing the self managed learning programme, the board members attended a workshop on mentoring and coaching.

In designing the senior management programme it was clear that the links between it and the strategic direction of the business had to be made explicit. Also, the programme needed to mirror the new culture being established. A more entrepreneurial culture needed more entrepreneurial managers. But managers would not become more entrepreneurial by sitting in classrooms listening to lectures, or by doing case studies. This would produce people who could talk about being entrepreneurial, but they would not necessarily become entrepreneurial.

Self managed learning

The self managed learning approach addresses this issue. For instance, it demands that managers manage their own learning. They negotiate their own objectives, decide how to achieve them, how to measure them and how to integrate their learning with organizational needs. As part of the programme individual managers joined 'learning sets' with five or six other managers. These sets met once a month for a whole day. In this programme they met over a period of nine months, which constituted the first phase of the work. The sets provided a place to negotiate learning objectives, agree a written 'learning contract' to carry out these objectives and get support to implement the contract. At the end of the nine months the individuals in their sets were required to assess themselves against the objectives they had set. (Chapters 6,7 and 8 in Part Four explain more about self managed learning and how it works.)

The set is assisted in its working by a set adviser. This person's role is to help the set function. It is not a teaching role, nor is it the same as being a facilitator (as the term has come to be used in training and development circles). (This role is explained more fully in Chapter 9.) We initially chose 11 senior people from different departments of the company (mostly in the number two position in the department, just below board level) to act as set advisers. They attended a three-day workshop to develop their ability to fulfil the role, and they also received ongoing supervision and support from experienced set advisers (from outside the company) throughout the programme. This feature is important as it was part of our role to develop the strategic capability of the organization to continue to support this approach to learning. (Chapter 10 has more on the issue of developing set advisers.)

The first programme was launched with a two-day residential event. The role of external consultants (such ...