Chapter 1

Afterthoughts on The Origins of the Liturgical Year

Thomas J. Talley

The disciplines of musicology and liturgical history have long been intimately intertwined, but expert address to both of those has seldom been more clearly accomplished than by James McKinnon. Therefore, I was deeply honored to be invited to participate in a conference celebrating his life and work, the occasion for which this study was written. When, some six months prior to the conference, I was first approached about making a presentation, it was intimated that one reason for extending the invitation to one who is not a musicologist was Professor McKinnon’s expressed appreciation of my work on The Origins of the Liturgical Year. That work is a historical study of the evolution of the festivals and seasons that celebrate the Christian mystery of redemption around an annual cycle. The work first appeared in 1986, and enjoyed a much-needed ‘Second, Emended Edition’ in 1991. While that took care of most of the more painful failures of proofreading, I now know of two minor mistakes still in the text.1 Beyond that, years of teaching from the book and consideration of the reviews of it by others led me to undertake a more extensive revision a few years ago. That work, hardly begun, was cut short by serious attenuation of my central vision owing to macular degeneration. So when I was invited to present some material on the liturgical year to the conference, I was happy to have such an opportunity to confess some of the things I wish were different about that book.

Just to get an initial and painful problem out of the way, the book is, at least in the testimony of some, virtually unreadable. It was written, I now recognize, for the community of scholars, and could easily be made more ‘reader-friendly’ even within my stylistic limitations. As one example, I was asked to teach a course based on the book at Yale Divinity School in the spring of 1986, and on my first day in class I was set upon by one student who charged, ‘you used a word that isn’t even in the dictionary’. The offending word, I learned, was ‘Quartodeciman’, a term used to characterize those who kept the annual Pascha on the fourteenth day of the first month of spring, without regard to the day of the week. While I am sure the student would not suggest that our technical vocabulary should be limited to a standard desk reference dictionary, I like to think that had I been less afraid of delineating the obvious, it would have occurred to me to introduce that term more carefully. In fact, the initial discussion of the Asian custom of keeping Pascha on a fixed date, I now recognize, uses the term ‘Quartodeciman’ in a way that is open to the charge of mild anachronism, though no one has challenged it on that basis, so far as I am aware. In fact, the Asian fixed-date Pascha, kept on the same day as the Preparation for the Jewish Passover, 14 Nisan, came to be labeled ‘Quartodeciman’ only during the paschal controversy later in the second century. The Asian Christians who continued the observance of Passover did not call themselves ‘fourteenthers’, or Quartodecimans.

In connection with the Asian custom of observing Pascha on a fixed date, I remain dissatisfied with my introduction of the Asia Minor calendar to explain the significance of 6 April as a date still used by Montanists to determine the date of Pascha in the fifth century, according to the Constantinopolitan historian Sozomen (d. ca. 450).2 While my description of the earlier, pre-Constantinian calendar of Asia Minor is intelligible, I believe, it is not compellingly clear. At the suggestion of a friend, Richard Norris, I prepared for the revision a table in three columns, showing: (1) the dates from 24 March through 6 April in the format familiar to us, (2) the Roman designation of those dates, counted as days before the kalends of the following month, or before the nones or ides of that month, a matter that itself needed more precise treatment, and (3) the equivalent days in the Asian month of Artemisios, numbered 1 through 14. Such a table, I hoped, would make clear how the fourteenth day of the first spring month came, after the establishment of Constantinople, to be known as 6 April. Some Asian Christians of the second century, cut off from the sages of Palestine who determined empirically whether, in a given year, the month preceding Nisan would be repeated to compensate for a lunar calendar whose twelve months fell eleven days short of the solar cycle, finally abandoned the Jewish lunar calendar. They had recourse instead to the solar calendar with which they were familiar, setting Pascha on the fourteenth day of the first month of spring in that calendar, the month sacred to Artemis and called ‘Artemisios’. The understanding of this calendar of Asia Minor is critical for the interpretation of Sozomen’s testimony, and of what August Strobel calls ‘solar quartodecimanism’.3

It remains surprising to me that liturgical scholarship (my own included, for too long) has been, for the most part, so unconscious of the significance of that calendar. The resource on which I depended for treating of that calendar was E. J. Bickerman,

The Chronology of the Ancient World, but the calendar was given more detailed treatment by Theodor Mommsen in an essay I was able to locate at Dumbarton Oaks only after the second edition of

Origins was in press.

4 Fundamentally Julian, this Asian recension, established in 9 BC, took the birthday of Augustus on 23 September, the ninth day before the kalends of October, as its New Year’s Day, the first day of a month called Kaisar (or Kaisarios), and so began each month nine days prior to its Roman equivalent. This made the Roman 24 March, the ninth day before the kalends of April, the first day of Artemisios in Asia Minor, and the fourteenth day of that first spring month, a solar equivalent to the Jewish Day of Preparation of the Passover, the day of the crucifixion, corresponding to the Roman 6 April. After the founding of Constantinople, the Roman calendar was adopted, and its designations displaced the old Asian calendar designations. This redesignation did not erase significant dates from memory,

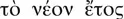

but translated them into the Roman terminology. So it is, for example, that the tenth-century Typikon of Hagia Sophia preserved in MS Hagios Stauros 40 in the Jerusalem patriarchal library still notes that 23 September is New Year’s Day,

.

5 This is why Sozomen’s Montanists reckoned Pascha from 6 April, the Roman redesignation of 14 Artemisios.

Roland Bainton, to whose work we all owe a debt that will not soon be discharged, was unaware of this, and, convinced that 6 April was not a significant solar date, supposed that the date mentioned by Sozomen was computed back nine months from 6 January (a date for the nativity that Bainton took to have been adopted from a pagan festival, to arrive at the date of Christ’s conception, often identified with that of his death).6 As I hope will become clear shortly, that reverse computation from the nativity date to the date of the conception leaves unexplained the identification of the dates of the conception and death of the Lord. I shall be concerned shortly to accuse myself of a similar flaw of argument in another context. In any case, 6 April is not, as Bainton believed, a day of no solar significance, but the translation into Roman terminology of what had been designated the 14th day of the first month of spring in Asia Minor, a solar calendar equivalent to the lunar 14 Nisan, the Preparation of the Passover, and the day of the crucifixion according to the chronology of the Fourth Gospel.

Also in need of more explicit treatment is the difference between that Asian paschal date, 14 Artemisios, later known as 6 April, and the Western dating of the crucifixion to Friday, 25 March, in the year that would come to be designated AD 29. While both dates, 6 April and 25 March, would be associated with the crucifixion, they were not two different answers to the same question, but answers to two different questions. The question in Asia Minor was, ‘how can we observe Passover on the fourteenth day of the first month when we don’t know which month is first because the rabbis decide that ad hoc?’ The question at Rome was, I suspect, ‘how can we reasonably keep the death dates of the martyrs if we do not know the date of the Lord’s death, which they emulate?’ Committed to ending the fast of Pascha on Sunday, the West did not seek a standing solar equivalent to the biblical date, but rather sought to know the year of the Lord’s death and the Julian date of the Preparation of the Passover, 14 Nisan, in that year. The Asian question was liturgical, the Western was historical.

However, this distinction between a historical date and that of a liturgical festival is not a simple matter, and some dates arrived at as historical can become liturgical observances. Our earliest source for the observance of the nativity on 25 December, the almanac assigned to the Chronographer of 354, gives a list of martyrs’ memorials that begins with a notation against the eighth day before the kalends of January, 25 December, natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae.7 That table of liturgical festivals of fixed date makes no mention of 25 March nor does it mention the day of the Lord’s passion. That was not an observance of fixed date, but was moveable, and always on Friday. Nonetheless, the Fasti Consulares in that almanac do assign the passion to the consulates of the two Gemini, AD 29: ‘His consulibus Dominus Iesus Christus passus est, die Veneris, luna quartodecima’.8 The same list assigns the nativity of Christ to the consulates of Caesar and Paul, AD 1. Both are recorded as historical dates, but only the nativity became a festival of fixed date.

Epiphanius reports some Quartodecimans who observe Pascha on 25 March, and we shall return to that shortly. It would be unwise, however, to leap to the supposition that wherever we encounter a calendrical note assigning the death or even the resurrection of the Lord to 25 March, as happens in some later medieval calendars, we have run across a wild strain of solar Quartodecimanism. Sources that clearly end the paschal fast only on Sunday nonetheless insist that the Lord died on 25 March. By the fourth century, many of these sources will assign his conception to the same day, but this cannot be taken as testimony of a liturgical feast of the Annunciation.

I mentioned above Bainton’s failure to account for the identification of the dates of Christ’s death and conception. I now recognize that I made that more difficult than it needed to be through a serious tactical blunder in Part II of my work, by its treatment of Christmas before dealing with the Epiphany. While the introduction of some Talmudic material identifying the birth and death dates of the patriarchs provided a somewhat broader base for the introduction of Duchesne’s computation hypothesis, it provided no rationale for the identification of Christ’s conception and death dates. Duchesne had argued that the dates of Christ’s death and conception were reckoned to be the same because a symbolic number system is intolerant of fractions. This determination of the conception date, he continued, would allow the computation of the nativity date nine months later, on 25 December (counting from 25 March) or 6 January (counting from 6 April).9

When we look rather at the Asian fixed-date Pascha, it becomes clear that, as the only annual feast of Christ in the second century, Pascha celebrated the entire mystery of redemption, including the incarnation as well as the death and resurrection of the Lord. Such a paschal homily as the Peri Pascha of Melito of Sardis testifies to the inclusion of the conception in the womb of the Virgin among the themes of the festival, focused in the first instance upon the Lord’s passion and death. The date of that festival, eventually known as 6 April, had enabled the setting of the birth date nine months later, on the date known to Clement of Alexandria as 11 Tybi, the Egyptian equivalent to the Roman 6 January, although other scholars have read this passage of Clement’s Stromateis to place the nativity on 18 November. This revised reading of Stromateis I.21.145–6 was the most brilliant achievement of Roland Bainton’s doctoral research on Basilidian chronology, and seems to have gone unnoticed until he recast it in his article ‘The Origins of Epiphany’. One could wish for parallel evidence setting the birth on 6 January from Asia itself, but the spread of that date to Egypt by the end of the second century is all the more impressive in view of Alexandria’s Sunday Pascha, as opposed to the fixed-date Pascha in Asia.

Some argument has been generated by my not well-disguised preference for Duchesne’s computation hypothesis, setting the birth date nine months after the date of Christ’s death and conception, over the more long-standing ‘History of Religions’ hypothesis that saw the birth date as taken from a pagan festival. Both remain hypotheses, and both continue to find adherents. But the inadequacy of the ‘History of Religions’ explanation is much more evident in the case of 6 January than for 25 December. Further, in light of the paschal homily of Melito, we can see clearly how the incarnation came to be associated with the day of the Lord’s death as a subsidiary theme in a unitive paschal liturgy. But that association is not so easy to understand in the case of the Western historical date for the passion. In Asia the incarnation and the passion were themes in a liturgical celebration of the entire mystery of redemption. One can imagine such an identification of the dates of conception and death being applied subsequently to the Western historical date for the passion. It is more difficult to account for that identification without reference to the Asian paschal liturgy. The Asian Quartodeciman observance on 25 March, reported by Epiphanius,10 may have led to the assignment of the conception to that date, if its supporters, like earlier Quartodecimans, celebrated the entire mystery of redemption at Pascha, including the incarnation with the passion and resurrection. The assessment of his testimony, however, would still be dependent upon such an argument as can be made from second-century Asian preaching at a Pascha nine months before 6 January. That is why I deeply regret addressing the history of Christmas before exploring the festival of the Epiphany. The argument is much more compelling if we look first at the Epiphany, nine months after the paschal liturgy that took note of the conception of the Lord, along with his death.

As for Christmas itself, the ‘History of Religions’ hypothesis is more impressive, since we have a definite festival on the nativity date itself, Dies natalis solis invicti, and can date its establishment to the reign of Aurelian, and to the year AD 274. By that time, however, the assignment of th...