CHAPTER 1

Language

Af Somaaliga wa mergi.

[The Somali language is sinuous.]

(Somali proverb, quoted in Laitin 1977: 31)

Minority takes translation on a creative line of flight.

(Venuti 1998: 144)

Upon initial inspection, the most salient and distinctive visual trait of Somali Italian literature is the lexical insertion of Somali words, which provides a good example of what Deleuze and Guattari refer to as the deterritorialization of language. Deleuze and Guattari recognize that minor writers modify their own language and learn ‘to be a foreigner, but in one’s own tongue, not only when speaking a language other than one’s own. To be bilingual, multilingual, but in one and the same language, without even a dialect or patois’ (1987: 98). Minor literature attempts to make one become ‘a nomad and an immigrant and a gypsy in relation to one’s own language’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1986: 19). In other words, deterritorialization refers to a deliberate operation through which a dominant language is deprived of its sense of national belonging. Using Kafka as an example, Deleuze and Guattari recognize a triple linguistic impossibility in his writings, namely ‘the impossibility of not writing, the impossibility of writing in German, the impossibility of writing otherwise’ (1986: 16). According to Paul Bandia, this ambivalent relation with language resembles that of African European writers, who have to confront ‘the impossibility of writing in the language of the oppressor with which he/she is intimately involved, as well as the impossibility of doing otherwise (i.e., of not writing in the language of the oppressor)’ (2006: 153).

Although the concept of deterritorialization offers important insights with which to approach the writings by multilingual subjects, Deleuze and Guattari do not analyse in detail how deterritorialization might be performed, or how its concrete realization not only envisions a different notion of identity but also serves a political purpose. They write that Kafka ‘turns syntax into a cry that will embrace the rigid syntax’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1986: 26), thus identifying a kind of linguistic deteritorrialization that is similar to the practices of code-switching between Creole or pidgin languages and the standard language, which are frequent in French and English postcolonial literature (Bandia 2008: 122, 147; Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin 2002: 65–71). This description does not entirely fit Somali Italian literature, where a foreign lexicon is most often introduced into the text, rather than modifying standard Italian.

Paul Bandia provides a more useful indication on how to investigate linguistic deterritorialization in a postcolonial context, claiming that translation can serve as a metaphoric paradigm to be used in analysing postcolonial writings. Bandia argues that ‘while interlingual translation usually involves importing foreign language elements into one’s own culture, postcolonial intercultural writing as translation involves a movement in the opposite direction, an inverse movement of representation of the Self in the language of the Other’ (2008: 3). Although noting a difference between translation, ‘the movement of text from a source language to a target language’, and the ‘ “inner translation” that occurs when writers write in a second language’, Bill Ashcroft also recognizes that writings by postcolonial authors could be the intersection where ‘Translation Studies and Post-colonial Studies meet’ (2010: 25). Ashcroft argues that a metaphoric resemblance between postcolonial writings and translations is found in the fact that they both are interpretations of at least two cultures and present a specific viewpoint on each of them. Both translation and postcolonial writing identify the distinct position of both the translator and the translingual writer with respect to the two (or more) languages and cultures to which he or she belongs (Ashcroft 2010: 36). Like translators, translingual writers have often been considered passive inheritors of diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds and as neutral presences, thus negating their role as interpreters. However, they are not at all neutral, and must constantly engage in a creative adaptation and interpolation of their culture by putting into practice both a linguistic and cultural operation of interpretation (Tymoczko 2002: 20). Translingual writers position themselves in relation to both languages and cultures to which they belong through the choice of different strategies, which are related to translation processes and might range from glosses, explanations, paraphrases, and paratextual interventions.

Analysing postcolonial writings through translation theory is a recent approach, made possible after the ‘cultural turn’ in translation studies, when translated texts started to be seen as the result of a negotiation between cultures and of a process of rewriting rather than a transaction between two languages or the restitution of a set of phrases (Bassnett 1998: 123). In other words, each language is culturally bound, but culture is in itself a permeable space of continual interaction, where concepts can be shared. The intercultural translation we encounter in Italian transnational and translingual writing challenges the traditional binary notion of translation, which relies on a dichotomy stemming from the monolithic categorization of origin and target. Intercultural writings negotiate between two or more culture-bound languages by creating a linguistic hybrid, in which non-related languages interact. Cultural plurality and the heterogeneity of postcolonial hybrid language could therefore be analysed through the theory of translation since it deals with matters of translingualism and transnationalism by its very nature.

Working from these assumptions, this chapter analyses the presence of Somali lexical interventions in the Italian text, and demonstrates that they are the most evident trace of a broader and more complex translatorial process. In particular, I will follow Lawrence Venuti’s invitation to look at what Deleuze and Guattari consider minor cultures through translation, which has long been viewed as

a minor use of language, a lesser art, an invisible craft [since] it aims to communicate what is by definition marginal in the translating culture: the foreign, the linguistic and cultural differences that demand radical rewriting in another language because they are not familiar or intelligible. (Venuti 1998: 135)

Moreover, this chapter identifies how different strategies through which foreign terms are present in the Italian text position the translingual writer in relation to the cultures and languages of which he or she is master. These strategies can be divided into three main categories whose theoretical models derive from Venuti’s translation theory, which he outlines in The Translation Studies Reader (2000): thick translation, foreignizing translation, and domesticating translation. First of all, approaches that are designed to show the distance between Italian and Somali through the use of paratextual remarks are analysed in correlation with Kwame Anthony Appiah’s concept of ‘thick translation’. Secondly, an account is given of those writings that present untranslated Somali signifiers. I will analyse in what sense non-translation might still be considered a form of cultural translation. This translatorial method is examined using Jacques Derrida’s foreignizing translation theory. Thirdly, texts that domesticate Somali language into Italian and limit the influence of heterogeneous linguistic presences are discussed by drawing a parallel with Eugene Nida’s concept of communicative translation. The division into these three categories follows a chronological model that illustrates a movement away from strategies that highlight the distance between Italian and Somali cultures towards strategies that show the proximity between the writer and the Italian readership. In this sense, the model of ‘thick translation’ is chronologically antecedent to the ‘foreignizing’ and the ‘communicative’ models, which represent the most recent outcomes of postcolonial Italian writings.

As the analysis will demonstrate, these three strategies should not be considered mutually exclusive since they are often used in combination. For example, within the same work, Somali terms can at times appear with Italian translations, although most of the Somali terms are left untranslated. As the analysis will point out, even if these strategies are associated with the literary work in which they are prevalently used, they should not be generalized since they might entail completely different effects if applied to other contexts. Moreover, the analysis of hybridization should not be divorced from a broader analysis of linguistic and stylistic choices in these texts, since the linguistic format in itself does not determine the linguistic and identitarian position of each writer. The last part of the chapter aims to complete, expand, and speculate on Deleuze and Guattari’s definition of deterritorialization as inextricably related to political resistance. It takes its lead from Venuti’s assumption that acts of translation by minorities

can be described as an act of violence against a nation [...] because nationalist thinking tends to be premised on a metaphysical concept of identity as a homogeneous essence, usually given a biological grounding in an ethnicity or race and seen as manifested in a particular language and culture. (2013: 116)

This chapter demonstrates that the insertion of foreign expressions enacts a process of dislocation which questions the supposed unity of the dominant Italian language and has the power to take readers away from the coded message of language, by detaching them from the language they regard as their own.

Translating the Distance: Footnotes, Parallel Texts, Glossaries

Early texts written by authors of Somali origins in Italian employed paratextual remarks to explain and justify the presence of foreign terms, such as footnotes, facing-page translation of the Somali text, and glossaries. For instance, Shirin Ramzanali Fazel’s autobiographically inspired text Lontano da Mogadiscio and Sirad Salad Hassan’s Sette gocce di sangue present italicized Somali expressions whose meaning is provided in a footnote. These paratextual elements might be explained by the fact that Sirad and Shirin are among the first immigrant authors to write in Italian without the help of a co-author.1 Footnotes were therefore necessary to accustom the Italian readership to the in-text insertion of foreign languages and to introduce Somali culture into the Italian literary scene. This aspect appears evident in Sirad’s ‘Breve storia della Somalia al tempo del nostro racconto’ [Short Story of Somalia at the Time of Our Narration], a paratextual remark at the end of Sette gocce di sangue (1996b: 113–21). Lontano da Mogadiscio and Sette gocce di sangue employ a standard form of Italian, which might be seen as a way to counter the prejudice of Italians towards immigrants as persons who are unable to speak their language. As Shirin clearly highlights, many Italians could not believe that a person of African origins could speak Italian, and sometimes they even answered her using the infinitive tense as if she were not able to conjugate Italian verbs (2013: 108).

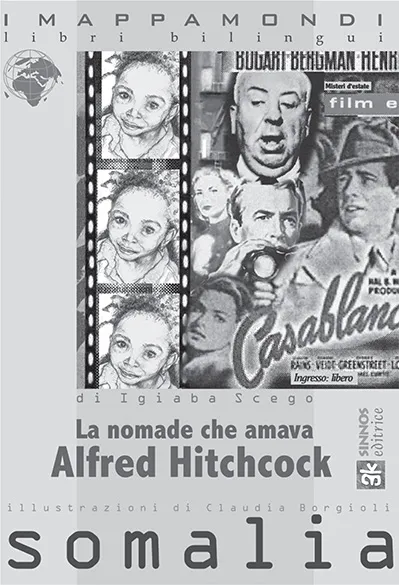

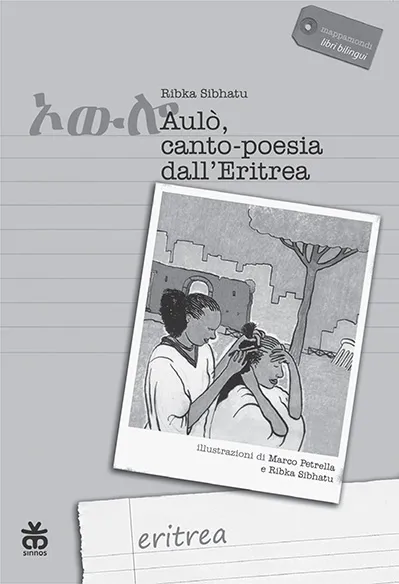

Igiaba Scego’s La nomade che amava Alfred Hitchcock. Ari raacato jecleeyd Alfred Hitchcock [The Nomad Who Liked Alfred Hitchcock] (2003; Fig. 5) also provides a good example of texts that employ paratextual remarks with the purpose of foregrounding Somali culture. The book is included in the collection I mappamondi [World Maps], a series that is characterized by three main features: a first-person internal narrator tells his or her experience of migration to Italy and the history of his or her country; each volume presents two versions of the same text both in Italian and in the author’s first language, and these texts have a clear didactic purpose that is signalled by the inclusion of glossaries, footnotes, illustrations, traditional fairy tales, recipes, and addresses. Many scholars have praised the cultural operation performed in these volumes and have focused in particular on Ribka Sibhatu’s Aulò: canto-poesia dell’Eritrea [Aulò: Song-poetry from Eritrea] (1993; Fig. 6), the first postcolonial text to use this specific format and the model of Scego’s text (Scego 2007: 71).2

The double title of the texts included in I Mappamondi series exemplifies the operation of cultural translation at work. According to Loredana Polezzi, in the I Mappamondi series the boundaries between target and source text are blurred since the two texts are inseparable, therefore writing and translation are conflated (2008: 123). In other words, it is not always possible to understand in which language the texts included in the collection I Mappamondi were originally conceived and written. This linguistic characteristic distinguishes the bilingual novels in the I Mappamondi collection from other bilingual texts such as the anthology of short stories Il coccodrillo che prestò la lingua allo sciacallo e altre favole dalla Somalia [The Crocodile that Lent its Tongue to the Jackal and Other Stories from Somalia] (1997), which presents the original Somali text with Suad Omar Esahaq and Roberta Valetti’s Italian translation on the opposite page. Il coccodrillo conceptualizes translation as a one-way movement from Somali to Italian and presumes the existence of source and target texts. Il coccodrillo shows its readership the presence of a minor language that has generated the Italian text, but also foregrounds the figure of an Italian reviser, who guarantees the linguistic correctness of the Italian version.

FIG. 5 The book cover of La nomade che amava Alfred Hitchcock. Ari raacato jecleeyd Alfred Hitchcock (2003). Courtesy of Sinnos Editrice

FIG. 6 The book cover of Aulò: canto-poesia dell’Eritrea in its third edition (2009). Courtesy of Sinnos Editrice

The presence of a minor language along with the dominant language in the series I Mappamondi can be seen as a political operation. According to Ponzanesi, the bilingual format of these texts reveals ‘[an act of dialogism and not only of resistance] against the ethnocentric appropriation of the Italian language and also a disconcerting way of responding to the white gaze, by literally facing the text in Italian’ (2004: 182). However, Ponzanesi may overestimate the political function of bilingual texts, since it is debatable whether a text that does not directly hybridize and change the dominant language might really have a strong political impact. The bilingual self-translated texts present two separate and yet intrinsically correlated versions. The distance between the two versions suggests a non-integration and unassimilability between the two languages, and implies a separate encounter with each of these texts. Cultural exchange passes more frequently through the implicit author who is able to master both languages than through the text, which is ideally usable in its entirety only by a potential reader who has mastered both Italian and Somali. The Somali text acquires the metonymic function of a silent cultural sign for the Italian readers who are not fluent in Somali. The cultural dialogue therefore seems to be conveyed only partially through language.

The supremacy of the Italian over the Somali version seems apparent in La nomade, and many passages provide textual evidence that the Somali version was translated after the Italian version with the collaboration of a Somali native speaker (Scego 2007: 71). The Italian text frequently includes footnotes that suggest the need of additional explanations in order to approach another culture without knowing its linguistic background. In addition, gloss translations or in-text explanations of some words are used, which convert the Somali version into a decorative corollary of the Italian text, and indicate that the two texts are not correspondent. This fact is evident when the meaning of certain Somali words or expressions is clarified at length in both texts. For instance, the description of the five pillars of Islam might be found redundant by Somali readers, who already have an understanding of their meaning in Somali (Scego 2003: 118). The predominance of the Italian text is also apparent in a passage where both versions of the text explain the meaning of Somali words, and Somali words are listed in the same order as they are in the Italian version (Scego 2003: 112). Simply stated, the Somali version is presented not merely as a subsequent translation of the Italian text but also as subordinate and secondary to it. This disregard for the Somali version violates the principle of reciprocity that Tullio De Mauro recognizes as an essential condition of the volumes: ‘Questi testi bilingui [sono] in grado di favorire la conoscenza reciproca di ragazzi che vengono da tradizioni culturali diverse’ [these bilingual texts can favour the reciprocal knowledge of young adults who come from different cultural traditions] (2003: 7). La nomade seems to be slightly different from Aulò, since Ribka’s work has not been entirely conceived for ‘an audience of Italian native speakers’ but ‘one that instead belongs to the writer’s language of origin’ (Romani 2001: 373).

The predominance of the Italian text over the Somali version in La nomade is perhaps not surprising, since Scego is an Italian native speaker who lived in Somalia ‘per un anno e mezzo’ [for one year and a half ] (Scego 2010c: 149). Significantly, she argues that:

La Somalia è stata una meteora nella mia vita. Essendo nata in Italia all’inizio non riuscivo proprio a capire che cosa fosse questa Somalia e francamente ne avevo molta paura. Avevo sviluppato una fantasia personale sul mio paese d’origine: credevo fosse un paese rosso, una sorta di Marte terrestre. Fu grande la mia delusione quando, all’età di otto anni, mi accorsi che la Somalia non era rossa come Marte. (Scego 2003: 9)

[Somalia has been a meteor in my life. I was born in Italy. I could not understand what Somalia was, and to be honest I was afraid of it. I developed a fantasy about my country of origin: I thought that it was a red country, a kind of terrestrial Mars. I realized with disappointment when I was eight years old that Somalia was not red like Mars.]

Rather than fully bringing into play her entire linguistic potential as a native speaker, Scego adopts an oversimplified style that recalls the non-elaborated standard language of the writings by immigrants that are included in I Mappamondi. The choice of the simple usage of the Italian language in this book series was justified by the pedagogical function of these books and by the linguistic difficulties in writing in Italian for non-native speakers. On the other hand, Scego’s first-person narration of her mother’s story of immigration to Italy through a simple language is a fictional construction since Scego was born and raised in Rome, and she is an Italian native speaker.

The choice of dealing with controversial matters like religion, infibulation, colonialism and racism through a language that is oste...