- 514 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Studies in Seventeenth-Century Opera

About this book

The past four decades have seen an explosion in research regarding seventeenth-century opera. In addition to investigations of extant scores and librettos, scholars have dealt with the associated areas of dance and scenery, as well as newer disciplines such as studies of patronage, gender, and semiotics. While most of the essays in the volume pertain to Italian opera, others concern opera production in France, England, Spain and the Germanic countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Studies in Seventeenth-Century Opera by BethL. Glixon, Beth L. Glixon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del mundo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Seventeenth-Century Opera: The Early Years

[1]

Singing Orfeo: on the performers of Monteverdi’s first opera

Tim Carter is Professor of Music at Royal Holloway, University of London. His doctoral research at the University of Birmingham was on Jacopo Peri. He has held fellowships at the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Villa I Tatti, Florence (1984–5), and the Newberry Library, Chicago (1986), and has been joint-editor of Music & letters. A book on Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro was published in 1987; in 1990 he produced a much revised edition of Denis Arnold’s “Master musicians” study of Claudio Monteverdi; his Music in Late Renaissance and Early Baroque Italy appeared in 1992; a translation of Paolo Fabbri’s Monteverdi (1985) was published in 1994; and he was joint-editor of “Con che soavità”: essays in Italian Baroque opera, song, and dance, 1580–1740 (1995). His collected essays and articles on music in Italy ca. 1600 will shortly be published in two volumes by Ashgate in the “Variorum collected studies” series.

Tim Carter e Professor of Music al Royal Holloway, University of London. Jacopo Peri e i primordi dell’opera a Firenze hanno costituito il tema della sua dissertazione dottorale all’Università di Birmingham. Ha ottenuto borse di studio allHarvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Villa I Tatti, di Firenze (1984–5) e alla Newberry Library di Chicago (1986) ed è stato co-direttore di «Music & letters». Ha pubblicato i seguenti volumi: un libro su Le nozze di Figaro di Mozart (1987), una versione ampliata dello studio di Denis Arnold su Claudio Monteverdi (Master musicians; 1990), Music in Late Renaissance and Early Baroque Italy (1992), la traduzione inglese di Monteverdi di Paolo Fabbri (1994) e, come co-curatore, Con che soavità: essays in Italian Baroque opera, song, and dance, 1580–1740 (1995). Una raccolta in due volumi dei suoi scritti sulla musica in Italia intorno al 1600 vedrà presto la luce nella collana «Variorum collected studies» dell’editrice Ashgate.

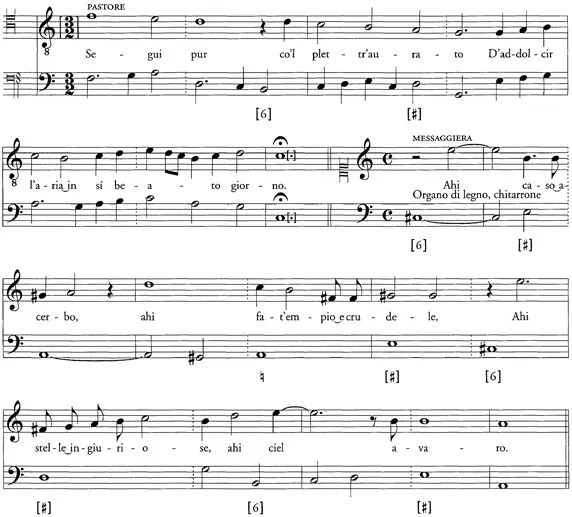

“Ahi caso acerbo”, cries the Messaggera as she disrupts the celebrations of Orfeo’s wedding to bring the disastrous news of Euridice’s death. Her abrupt entry on a high e” in act II of Monteverdi’s Orfeo (example 1) surely counts as the first coup de théâtre of early opera: neither Jacopo Peri nor Giulio Caccini had managed a similar effect in their respective settings of Euridice. The idea must have been partly Alessandro Striggios, whose striking exclamation gets built into the libretto of act II as a woeful refrain, first from a shepherd and then from the chorus. But Monteverdi did more than follow Striggios cue. That e”, the falling minor sixth and the disruptive sharpward harmonic move provide a powerful moment of musical dislocation to match the sudden turn from celebration to catastrophe; the rest of the act, indeed the opera, can never be the same.

But like all the best musical moments, it does not come out of the blue. Monteverdi has carefully prepared that e” by at least four striking entries earlier in the opera: in act I, the second half of the chorus “Vieni, Imeneo, deh vieni” (“E lunge homai disgombre”) begins on e”, as does the final chorus “Ecco Orfeo, cui pur dianzi”; in act II, two shepherds (tenors) sing “Qui le Napee vezzose” starting on e’, taken up by the five-voice chorus at “Dunque fa degno Orfeo” (e”), and Orfeos celebratory aria (in both senses of the term), “Vi ricorda, o bosdhombrosi”, begins again on e’.1 Before Messaggera’s

Example 1.CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI: Orfeo, Ricciardo Amadino, Venezia 1609, act II, p. 36 (with minor editorial amendments).

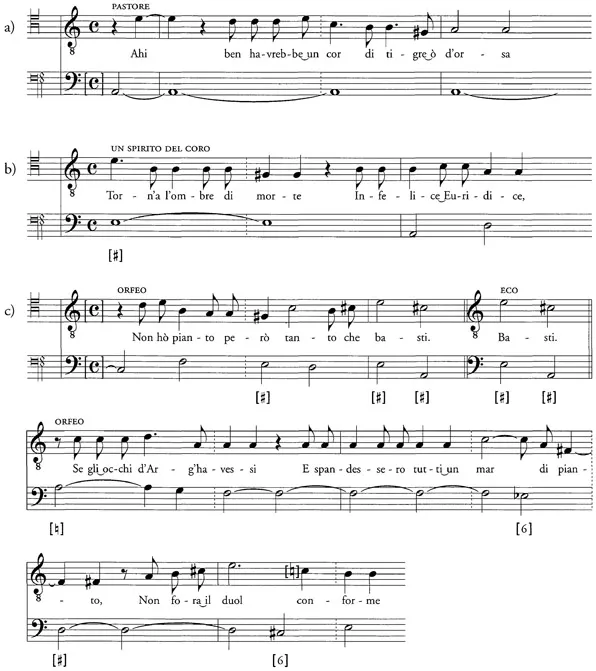

entrance, the high E (whichever octave) may have seemed just a convenient note on which to start; afterwards, however, it takes on ineluctably plangent overtones. As Messaggera tells of Euridice’s dying cry, “Orfeo”, she again reaches that e”. The shepherds repetition of “Ahi caso acerbo” later in the act keeps the e’ and its associations strongly in our memory, and presumably (if one can be forgiven the conceit) in his: at “Ahi ben havrebbe un cor di tigre o d’orsa” (example 2a) the same shepherd (it seems) begins on e’. It also recurs on key words in Messaggera’s last speech and in the final sequence of choruses of act II. So resonant does the note become that one cannot fail to make the association when in act IV a spirit of the Underworld pronounces sentence on Euridice after Orfeo’s disastrous failure of Plutones test: “Torn’a l’ombre di morte | infelice Euridice” (example 2b) begins on e’ and outlines the same falling minor sixth as “Ahi caso acerbo”. Even Orfeo and his kindly Eco in act v touch that e’ (example 2c) whether as poignant reminiscence or a further twist of the painful knife.2

Example 2.CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI: Orfeo: (a) act II (p. 39); (b) act IV (p. 81); (c) act V (p. 90).

A Schenkerian could, and probably should, make a point of those high Es as the recurring head-notes of some middleground descent or fundamental line whether on a local scale or in the longer term. Following Robert Donington, one could also make a point of them in other ways, granting that note – and the intervallic shapes associated with it – almost the status of a Leitmotiv evoking suffering and lost innocence.3 But there must be a more pragmatic issue at play here. To produce this effect, Monteverdi presumably had a soprano with a good top e”, and at least one tenor (playing a shepherd, a spirit and Eco) with a good e’, such that in both cases the composer felt encouraged to work with the grain of the voice. Those Es serve not only for musical and dramatic effect; they also act as ghostly echoes of the singers with whom Monteverdi collaborated in bringing his first opera to the stage before the Accademia degli Invaghiti on the evening of 24 February 1607.

We know surprisingly little about the first performance, and first performers, of Orfeo;4 the relative dearth of archival evidence for Orfeo – and similarly, for Peris Dafne (1598) and Euridice (1600) – suggests that however significant these works might (or might not) have been in artistic terms, they did not create sufficient difficulties or disruption to warrant the court administration grinding itself into motion and keeping record of the fact. An exception proves the rule: in preparing for Orfeo, the Mantuans found themselves short of competent castratos, and so Prince Francesco Gonzaga wrote to his brother Ferdinando, currently in Pisa, to see if a singer in Medici service could be borrowed for the occasion. As we shall see, the resulting exchange of letters concerning the Florentine castrato Giovanni Gualberto Magli’s coming to Mantua is of some importance. But we learn of the participation of the great virtuoso tenor Francesco Rasi in Orfeo – almost certainly in the title-role – only by way of a brief, isolated reference in a collection of poetry edited by the Mantuan Eugenio Cagnani in 1612;5 and of the other performers, we have scarcely a hint in the archives.

This is not to say that Orfeo did not make an impact on its Mantuan audience: Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga was so taken with the work as to order a second performance before the ladies of the city on 1 March, and to plan a third later in March or in April, probably for the proposed visit of Carlo Emmanuele, duke of Savoy (he never arrived). Mantuan letterati such as Cherubino Ferrari continued to praise the work;6 the score was published two years later by Ricciardo Amadino in Venice (the dedication to Prince Francesco is dated 22 August 1609); Prince Francesco contemplated staging it at least once more (in 1610); Francesco Rasi took it to Salzburg where it seems to have received regular performances from 1614 to 1619;7 Amadino printed a second edition in 1615; and Monteverdi remembered the opera fondly in his letters. Like all great works, Orfeo took on a life independent of the circumstances that gave it birth. But those circumstances surely conditioned its creation and realization, echoing through the score like those high Es redolent of a different time and a different place.

No one has yet asked why it should have taken over two years for Orfeo to reach the press;...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY OPERA: THE EARLY YEARS

- PART II MONTEVERDI AND CAVALLI

- PART III ITALIAN OPERA DURING THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

- PART IV OPERA OUTSIDE ITALY

- Name Index