- 632 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor

About this book

This study is the first to consider all three of Rachmaninoff's careers in detail. After surveying his place in Russian musical history and his creative activity, the author examines, with musical examples, each working chronological order against the background of the composer's life. Among the the many subjects upon which new light is shed are the operas, the songs, and the religious music. Rachmaninoff's remarkable career as a pianist, his style of playing and repertoire are analysed along with his historically important contribution to the gramophone and his work for the reproducing piano. The book includes a survey of his activity as a conductor. There are extensive references to Russian sources and the first appearance of a complete Rachmaninoff disconography is included. This book is the only comprehensive study in any language of the three aspects of Rachmaninoff's musical career and is a stimulating read for music lovers everywhere.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor by Barrie Martyn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Musica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicaPart I

RACHMANINOFF THE COMPOSER

RACHMANINOFF THE COMPOSER

1 Rachmaninoff and Russian Musical History

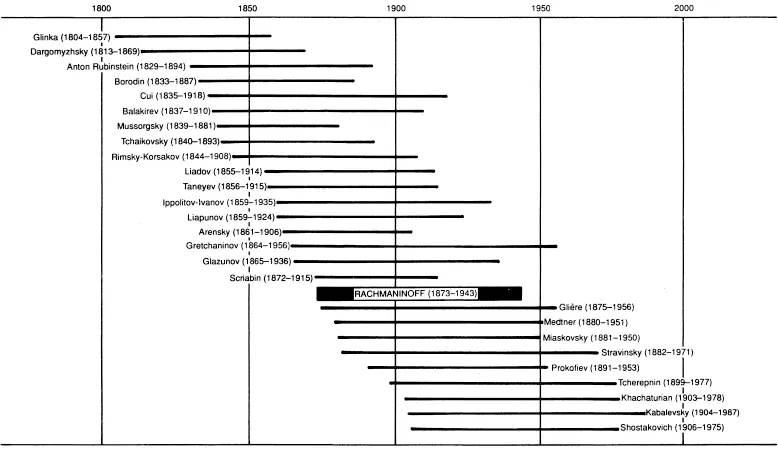

Rachmaninoff was born in 1873, one year before the first performance of Boris Godunov, forty years before Rite of Spring; Tolstoy was starting work on Anna Karenina. His close Russian contempories include Scriabin and Chaliapin, Diaghilev and Benois, Stanislavsky, Gorky, Rasputin and Lenin. The interval between the births of Glinka and Rachmaninoff – sixty-nine years – is almost the same as Rachmaninoff’s own life-span: he died a few days before his seventieth birthday, in 1943, in which year Shostakovich composed his Eighth Symphony and Miaskovsky his Twenty-fourth; Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony appeared the following year. Thus the fundamental fact about Rachmaninoff’s place in Russian musical history is that he stands Janus-like between the old Russia and the new, looking back to the flowering of Russian nineteenth-century ‘classical’ music as also ahead to the first generation of Soviet composers.

Although Glinka is traditionally cited as the founding father of Russian music, it in fact began to evolve many centuries before him.1 The first Russian composer known by name seems to have been Tsar Ivan the Terrible (1533–1584), but both church and folk music, from which all Russian ‘classical’ music is ultimately derived, reach back for their origins much further still. A native church music, the counterpart of Western Gregorian plainchant, developed soon after the conversion of Russia to Christianity in 988, either out of imported Byzantine chant or, as many Soviet musicologists claim, from the ancient folk melodies of the Eastern Slavs. Curiously enough, although the origins of Russian folk music are archaic, it was not until the end of the eighteenth century that the first collections were made,2 something that in retrospect was a hint that after so long a dormant period Russian music was at last about to take off.

The foundation by Peter the Great in 1703 of the city of St Petersburg inaugurated a century of unparalleled cultural development. The building and adornment of the new capital and the increasing brilliance of the Court attracted foreign craftsmen and creative artists in every sphere, especially during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762–1796). Many foreign musicians visited Russia or settled there, among whom Italians were particularly numerous, including such distinguished composers as Araja, Galuppi, Traetta, Manfredini, Sarti, Paisiello and Cimarosa, who created and then exploited in St Petersburg, as Handel had done in London, a vogue for Italian opera. But in music, as in the other arts, the assimilation of foreign influences itself sparked off indigenous talent, and by the end of the century Russian-born executants and composers had emerged in appreciable numbers. Native opera began to appear in the 1770s,3 much of it containing Russian folk music, though arguably it was not until the early years of the nineteenth century that it acquired a distinct, national character, after the Napoleonic Wars had stimulated a feeling for nationalism in Russian art generally. As Pushkin (1799-1837) began a literary renaissance, so it was through Glinka (1804-1857) that Russian music at last emancipated itself and established its own identity. The first performance of A Life for the Tsar in 1836 is usually seen as the inaugural event in the process, and for Tchaikovsky Kamarinskaya (1848) was the ‘acorn’ from which the oak of Russian symphonic music grew.

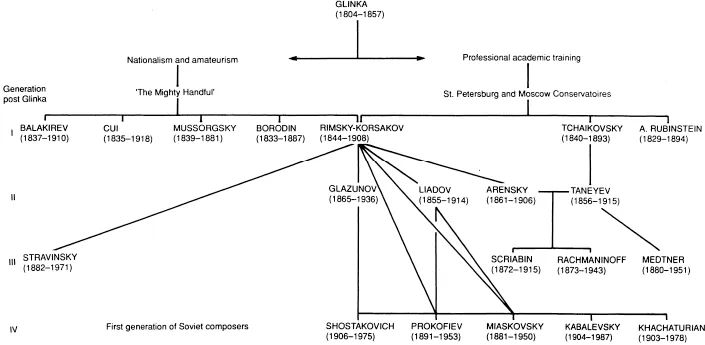

Glinka’s Russian feeling and the strong element of dilettantism in his musical make-up4 made the self-conscious nationalism and inspired amateurism of his spiritual heir Balakirev and his circle of Cui, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin seem a natural succession, as indeed at first it was, but even before ‘The Mighty Handful’ had acquired their sobriquet5 history changed course unexpectedly. With musical life in Russia now burgeoning, a demand was created for institutionalized academic and professional training, which was satisfied by the foundation in 1859 of the Imperial Russian Musical Society and subsequently of conservatoires in St Petersburg (1862) and Moscow (1866) under the direction of the brothers Anton and Nikolay Rubinstein. Their training in Berlin and, in Anton Rubinstein’s case, Vienna too, made it inevitable that the new Russian academies should be modelled on the Austro-German pattern.6

Balakirev promptly condemned the St Petersburg Conservatoire as a conspiracy ‘to bring all Russian music under the yoke of the German generals’, and through his efforts in the same year as its foundation a Free School was opened in opposition. Vladimir Stasov, the great critic and inspirational force in the arts in Russia, cited what he claimed to be European opinion in support of him: ‘Academies and conservatoires serve only as a breeding ground for mediocrities and help perpetuate deleterious artistic ideas and taste . . . [They] meddle most harmfully in the student’s creative activity. They dictate the style and form of his works [and] impose their own fixed practices on him.’7 As the supreme martinet, dogmatist and meddler in his colleagues’ musical affairs proved to be Balakirev himself, these words from his apostle were ironical indeed.

Inasmuch as the conservatoires failed to tap new veins of creative talent or to do very much for their outstanding students, they realized the forebodings of their critics. Rachmaninoff was a case in point. Allowed as a young teenager at St Petersburg Conservatoire to fritter away his time, he had to be taken away and brought sternly to heel by the Moscow pedagogue Nikolay Zverev. At Moscow Conservatoire, according to his own admission,8 he learned more about the nature of fugue from two chance lessons than from a whole year’s classes with Arensky, and his course in counterpoint, despite the impeccable credentials of the teacher, Taneyev, the ultimate Russian authority on the subject, also proved ill-spent. Rachmaninoff survived on his own talent; his classmate Scriabin left the institution without even gaining a diploma in composition. Although predictably unsuccessful in catering for creative genius, the conservatoires nevertheless served a valuable function in providing a thorough professional training for executants, and they performed the useful incidental service of conferring on their graduates the status of Tree Artist’, a title originally created by Catherine the Great only for architects and painters; by putting their graduates on a par the conservatoires gave social respectability to a profession previously classified as proletarian.

The case against academic training was rather undermined at the outset by the towering stature of the first composer to emerge from St Petersburg Conservatoire, Tchaikovsky, pupil of the arch villain Anton Rubinstein, who himself, at least in some of his later works, such as the ‘Russian’ Symphony of 1880 and the orchestral fantasy Russia of 1882, could be self-consciously nationalist. Though Tchaikovsky had severe reservations about the work of The Mighty Handful’ and their lack of professionalism, in some senses he might have been one of their number himself; he incorporated Russian folk music in his compositions, as in the Second Symphony; he was on friendly personal terms with the group – Romeo and Juliet was dedicated to Balakirev, The Tempest to Stasov; and, like all the others, he more than once accepted Balakirev’s detailed criticism and advice (both Romeo and the ‘Manfred’ Symphony owed their genesis to him). Conversely, Balakirev and the others in their turn all came to use classical contrapuntal techniques in their work,9 and all but Cui at least essayed a symphony, that symbol of classical tradition, as if this was the only way they could convince themselves they had musically come of age.

Even before Rachmaninoff’s birth the gulf between professionalism and amateurism had been bridged by Rimsky-Korsakov, who had won sufficient recognition and respectability to find an uneasy and incongruous niche in the musical establishment on the staff of St Petersburg Conservatoire, where he remained for thirty-seven years, mentor of the younger composers up to Stravinsky and Prokofiev, though not, to Rachmaninoff’s later regret, of Rachmaninoff himself. Glazunov, protégé of The Mighty Handful’, completed the process of reconciliation by combining in his music Russian nationalism with western tradition. After Glazunov all Russian composers, including Rachmaninoff but with the conspicuous exception of Stravinsky, learned their craft by the academic route and not the path of amateurism, which in retrospect was inevitably a dead-end.

By the time Rachmaninoff had graduated from the Moscow Conservatoire in 1892, whatever might once have been the collective identity and ideals of the nationalist group, and these were always more concepts in the minds of music critics than a practical reality for those involved, had long since ceased to exist. Two of their number were dead, Mussorgsky (1881) and Borodin (1887), and a new circle of lesser composers had emerged under the aegis of the timber millionaire and publisher Mitrofan Belyayev. The bilious Cui, who continued to compose for another quarter-century into ripe old age, then as now was known less for his music than for his writings (which include the much-quoted and notoriously damning review of Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony). Balakirev, once the leader and driving force, had gone through a psychological crisis, and although he had come out of seclusion to resume musical activity and indeed was to enjoy an Indian summer as a composer, h...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Rachmaninoff the Composer

- Part II Rachmaninoff the Pianist

- Part III Rachmaninoff the Conductor

- Notes

- Index of Rachmaninoff’s Works

- Index of Persons and of Works Referred to in the Text