eBook - ePub

Random Non-Random Periodic Faulting in Crystals

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Random Non-Random Periodic Faulting in Crystals

About this book

This book provides a comprehensive overview of stacking faults in crystal structures. Subjects covered include: notations used in representations of close-packed structures; types of faults; methods of detection and measurement such as X-ray diffraction, electron diffraction and other techniques; theoretical models of non-random faulting during phase transitions; specific examples of - close packed structures including, zinc sulphide, silicon carbide and silver iodide.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Random Non-Random Periodic Faulting in Crystals by M. T. Sebastian,P. Krishna,M.T. Sebastian,P, Krishna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Scientists may prefer order but nature seems to prefer disorder. Every model that the scientist develops has in it the elements of order but no model ever exactly describes reality. It only approximates to it. As students of nature, we scientists have no right to postulate what reality should be, we can only examine what it is. When we do that through our experiments and investigations we find that it never quite fits our models and descriptions, including our models of disorder! And yet, it is from the critical examination of these deviations that science has progressed in its understanding of nature. It is the so-called oddities of nature that contain in them the deeper secrets of its operation. This book describes one such oddity of nature which we have not yet understood fully – the occurrence and distribution of ‘faults’ in the stacking of atomic layers of structure in solids. The perfect crystal lattice is such a beautiful concept evolved by scientists that it almost seems a pity that Nature did not adopt it to make its solids!

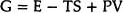

Thermodynamics tells us that a certain amount of disorder is to be expected as a part of equilibrium. The state of equilibrium for an interacting assembly of atoms is given by the condition that the Gibb’s Free Energy G, defined as

must be a minimum. Here E, the internal energy, stands for the total sum of the kinetic and potential energies of the constituent atoms. S, the entropy, depends on the state of order in the system and V, the volume, depends on the density of packing the atoms together. T and P are the temperature and pressure which are determined by the external conditions.

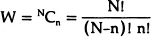

For a totally ordered structure the configurational entropy S = 0, since it is given by the Boltzmann equation

where W is the total number of ways in which the structure can be arranged with the same internal energy E. For a perfectly ordered structure W = 1 and S = 0. At T = 0, that particular ordered structure will be favoured for which E is minimum. In such an arrangement, all atoms have minimum potential energy and are therefore in equilibrium. This determines the perfect lattice structure of the solid. For a disordered structure, E increases since some of the atoms are no longer in their minimum energy environment and some bonds are broken. As this happens, the entropy also increases, since the disorder can be introduced in several equivalent ways (W) leading to a configurational entropy. For example, if there are n vacancies in a total of N atomic sites then

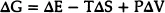

Therefore the change in the free-energy due to the disorder is given by

where ΔE is the increase in the internal energy due to the vacancies and ΔS = k loge W. The term PΔV is usually negligible in the case of solids unless one is working under conditions of very high pressure. Therefore

If ΔG is negative, the disorder leads to a lowering of the free energy and is therefore thermodynamically stable. If ΔG is positive then it leads to an increase in the free energy and the disorder is thermodynamically metastable.

Detailed calculations show that only point defects (vacancies and interstitials) produce a lowering of the free energy. Other defects like dislocations (line defects) and stacking faults (planar defects) in solids are usually metastable and lead to an increase in the free energy because their contribution to the entropy term (TΔS) is small compared to their effect on the internal energy (ΔE). A certain amount of point defects are thus expected to occur in all solids and to increase with rise in temperature, but dislocations and stacking faults are normally metastable defects which would disappear if sufficient activation energy was provided to make them mobile. They persist in solids since the energy required for their movement is high and not readily available at normal temperatures and pressures. One therefore expects a certain small amount of disorder to exist in solids and very special methods have to be used to grow perfect crystals of a material.

The occurrence of an odd stacking fault in a crystal structure is therefore not surprising, but what this book is concerned with is the very high concentration of stacking faults encountered in several close-packed materials like SiC, CdI2 and ZnS. Fault concentrations as high as 25% or more have been observed in crystals of these materials with the faults distributed sometimes randomly, sometimes non-randomly and in rare cases, periodically. Chapter 2 describes the different types of stacking faults encountered in close-packed structures and chapter 3 discusses the computation of diffraction effects produced by them on X-ray diffraction photographs, when the faults are distributed randomly in the crystal. Methods of determining the nature and concentration of faults present by comparing the theoretically predicted diffraction effects with those observed experimentally are discussed.

By a close-packed structure is meant here a structure in which one of the constituent atoms or ions occupies positions corresponding to those of equal spheres in a close-packing, with the other atoms or ions distributed in the voids. Such structures are conveniently described in terms of the ABC notation for close-packings of spheres though they may not be ideally close-packed. Normally in metals one encounters only the hexagonal close-packed ABAB … and the cubic close-packed ABCABC … structures, but in compounds such as SiC, CdI2 and ZnS, a whole range of poly type structures are encountered with periodicities ranging all the way from about 5A to some as large as 1500A or more. Some of these are disordered with a random distribution of stacking faults in them but one also encounters perfectly ordered long period modifications with a periodicity far greater than the range of any known atomic forces. There is controversy whether these long-period polytypes are stable thermodynamic phases of the compound or they are metastable modifications resulting from the kinetics of crystal growth or solid state transformations. We shall review the present state of our understanding of this phenomenon, but let us briefly consider first the thermodynamic factors determining a close-packed structure.

Consider an ideal close-packing of equal spheres. It can be described in terms of the well-known ABC notation for close-packing identical layers of equal spheres on top of each other. Each sphere has 6 nearest neighbours within its own layer, 3 in the layer above and 3 in the layer below, resulting in 12 spheres touching each given sphere. On top of each layer (A, B, or C) there are two ways in which the next layer can be stacked in a close-packed manner. Therefore any sequence of the letters A, B and C with no two successive letters alike represents a possible manner of close-packing the layers without violating the laws of close-packing or the nearest neighbour relationships. To examine which of these would be thermodynamically the most stable, let us consider the Gibb’s free energy, G = E − TS + PV, for these close-packings. Since the nearest neighbour relationships in all of them are the same, any difference ΔE in the internal energy would be due to interactions with more distant neighbours, and therefore negligibly small (ΔE ≃ 0). The density of packing is the same for all manners of close-packing the layers, therefore there are no differences in volume (ΔV = 0). It would therefore appear that the lowest free energy would result from maximising the entropy S, that is for a totally random arrangement of the layers. This would correspond to a sequence such as

which never repeats. What would the configurational entropy of such a totally random structure be?

If there are n layers in all to be close-packed over each other there are 2n − 1 ways of close-packing them since there are 2 ways of placing each layer, except the first one. The configurational entropy is therefore given by

This is very small compared with the entropy due to vacancies which can occur at atomic sites since the number of atomic sites is of the order of n3 for a crystal with nearly equal dimensions in all directions. Consequently the contribution of random layer arrangements to the total entropy of a crystal is also negligibly small. We have therefore a strange situation in which all the first order terms are vanishingly small in the expression

representing the free-energy change caused by random faulting or layer-disorder. In a situation such as this, the second order effects would become important in stabilizing the structure and that is precisely what one observes in some of these materials. Scientists have considered the effect of (i) impurities (ii) vibration entropy (iii) free-electron energy (iv) dislocations, in determining the structure. In metallic systems the free-electron energy is considerable and is known to determine the formation of long-period superlattices. They are equilibrium phases which result in alloys at particular electron-atom ratios. They form with the evolution of latent heat correspoding to the lowering of the free energy. But this is not true of dielectric materials like SiC, ZnS and CdI2, where there are no free electrons. Are there long range forces operating in these materials too? Is the formation of polytype structures some kind of a co-operative phenomenon? If so, what is the nature of the interactions? These are some of the questions scientists have tried to investigate and this book describes those attempts.

In the course of experimentally examining the layer disorder (stacking faults) in these materials it was found that the stacking faults do not always occur randomly. Theories of X-ray diffraction from one-dimensionally disordered close-packed structures containing a random distribution of stacking faults have been highly developed, but these could not explain the diffuse intensity distribution in many crystals observed experimentally. Our research group at the Banaras Hindu University has therefore developed theories of X-ray diffraction from crystals containing a non-random distribution of stacking faults. Such a distribution of faults arises when the crystal is undergoing a phase-transformation from one close-packed structure to another through the insertion of faults. If, for instance, the faults occur during a 2H (ABAB …) to 3C (ABCABC …) phase-transformation in a crystal, then the probability for a fault to occur is not the same on every layer of the crystal. The faults would occur preferentially at those sites which favour the transformation and therefore lead to the lowering of the free-energy. The stacking fault energy for such faults becomes negative in these circumstances and they nucleate and grow much more rapidly. The probability of faults to occur is therefore not the same on all layers and one must consider a fault probability distribution in order to understand the one-dimensional disorder in such crystals. This affords, a method of experimentally studying both the disorder present in a crystal as well as the mechanism of the phase-transformation.

If a crystal is undergoing solid state transformation from an ordered 2H (ABAB …) to an ordered 6H (ABCACB …) structure, it passes through several intermediate disordered states. If the transformation is slow, it can be quenched at different stages and the intermediate disordered structure examined by X-ray diffraction. It will produce diffuse X-ray intensities due to the disorder in the crystal. If one can develop a model of the disordered structure, one can compute the diffuse intensity that will be produced by the crystal on its X-ray diffraction pattern and compare it with that which is experimentally observed. It is in a sense like doing structure-analysis of a disordered crystal, only one has in this case an idealized statistical model of the disordered structure. Chapter 4 describes such studies performed in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Stacking faults in close-packed structures

- 3 Diffuse X-ray scattering from randomly faulted close-packed structures

- 4 Phase-transformations and non-random faulting in close-packed structures

- 5 Periodic faulting in crystals: polytypism

- Subject Index

- Author Index