eBook - ePub

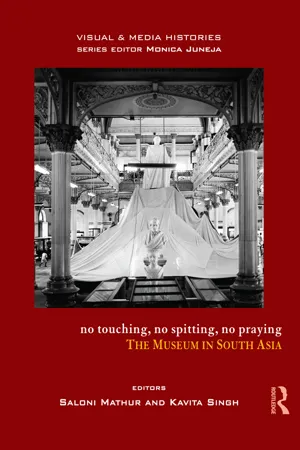

No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying

The Museum in South Asia

- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying

The Museum in South Asia

About this book

This volume brings together a range of essays that offer a new perspective on the dynamic history of the museum as a cultural institution in South Asia. It traces the museum from its origin as a tool of colonialism and adoption as a vehicle of sovereignty in the nationalist period, till its role in the present, as it reflects the fissured identities of the post-colonial period.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying by Saloni Mathur, Kavita Singh, Saloni Mathur,Kavita Singh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part 1

inaugural formations

1

transf

the transformation of objects into artefacts, antiquities and art in 19th-century India

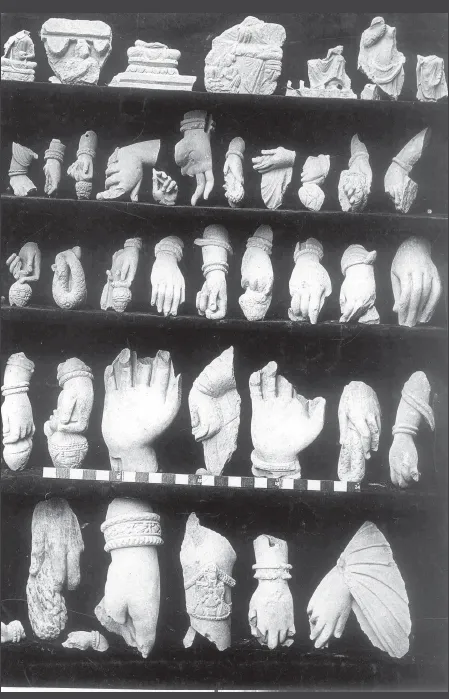

this chapter explores how things are fabricated and how they are transformed into objects that have value and meaning. The context is India and Great Britain in the 19th century.

An object, be it a fired piece of clay, a bone, paper with colours applied to it, a lump of metal shaped into a sharp point, a shiny stone which is polished, a feather, everything that we think of as existing in nature, can be transformed through human labour into a product which has a meaning, use and value.

A pot shard dug up and placed in a museum with a label identifying and dating it becomes a specimen along with thousands of others, which establish, for the archaeologist, a history. A bone found in a particular geological formation becomes a fossil for a paleontologist to read as part of an evolutionary sequence. For someone else this bone ground up becomes an aphrodisiac. The paper covered by paint is a god; in another time and place, it is a work of art. A piece of cloth fabricated for presentation marking the alliance between two families through marriage becomes a bedspread. A piece of metal shaped and sharpened and used as a weapon by a great warrior becomes for his descendants an emblem of his power, and is carefully stored away in an armoury, to be brought out in times of trouble to rally a failing army. In the hands of his enemies, it becomes a trophy. A piece of cloth worn by a religious leader at his moment of death has magical powers and for generations is revered as a relic.

The nominal subject of this volume (patronage in Indian culture)1 raises another set of questions about the production and meaning of objects, by shifting the focus from the fabricators of objects to those who commission, pay for, protect, support, and utilise the results of the labour and thought of the producers. In the language of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), a patron is ‘one who supports or protects, an institution, a cause, art or undertaking’, and patronage, it goes on to define in its ‘commercial or colloquial usage’, is ‘financial support given by the customers in making use of anything established, opened or offered for the use of the public’.2

The examples of this usage given in the OED all date from the 19th century. In this chapter I will explore patronage in an extended sense, as a relationship located in a political context, in which the British increasingly impose on Indians their own conception of value. The objects through which this relationship was constructed were found, discovered, collected, and classified as part of a larger European project to decipher the history of India.

It was the British who, in the 19th century, defined in an authoritative and effective fashion how the value and meaning of the objects produced or found in India were determined. It was the patrons who created a system of classification which determined what was valuable, that which would be preserved as monuments of the past, that which was collected and placed in museums, that which could be bought and sold, that which would be taken from India as mementoes and souvenirs of their own relationship to India and Indians. The foreigners increasingly established markets which set the price of objects. By and large, until the early 20th century, Indians were bystanders to the discussions and polemics which established meaning and value for the Europeans. Even when increasing numbers of Indians entered into the discussion, the terms of the discourse and the agenda were set by European purposes and intentions.3

From the inceptions of direct trading relations between Great Britain and India in the early 17th century, India was looked upon as the source of commodities, the sale of which in Europe and Asia would produce profits for the owners and employees of the East India Company. Textiles in bulk and value came to be the primary Indian product imported and sold by the Company in Europe. Hence it was through these textiles that India was primarily known to the consuming classes in Britain and Western Europe. The impact of Indian cloth was to play a major role in creating what Chandra Mukherji terms ‘modern materialism’, and the development of industrial capitalism, in the efforts of 18th-century British entrepreneurs to find technological means by which British labour could organise to compete with Indian-made textiles. One gets a sense of how deeply embedded Indian goods are in Anglo-American culture through our language, in which so many terms relating to cloth have their origin in India.4 In addition to those Indian products that were essentially seen as utilitarian goods, there was scattered interest in the 16th and 17th centuries in items thought of as curios and preciosities, or what today might be thought of as ‘collectibles’. These include odd paintings, both by Indians and Lusho-Indians, inlaid ivory chests and other items of furniture, jewellery and precious stones, swords and weapons to be used as decorative items.5

European interpretative strategies for ‘knowing’ India: 1600–1750

The major interpretative strategy by which India was to become known to Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries was through a construction of a history for India. India was seen by Europeans not only as exotic and bizarre but as a kind of living museum of the European past. In India could be found ‘all the characters who are found in the Bible’ and the ‘books which tell of the Jews and other ancient nations’.6 The religion of the Gentoos was described as having been established at the time of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, and preserved by Noah; or the religion of ‘the seed of those who revolted against Moses’ and the worshippers of the ‘molten calf’.7 The Brahmans were Levites or Nazarites; Jains, Rehabites. Indians were, for some Europeans, the direct descendants of one of the lost 10 tribes, for others manners and customs of Indians derived from the ancient Egyptians who were the descendants of Ham, the son of Noah.

The Bible and the medieval patristic literature offered another interpretation of the culture and religions of India for the European travellers: this was the home of the traditional enemies of Christianity, Satan and his devils. One of the earliest of the British travellers in India knew what the religion of the Gentoos was all about.

But above all, their horrid Idolatry to Pagods (or Images of deformed devils) is most observable: Placed in Chappels most commonly built under the Bannyan Trees. A tree of such repute amongst ’em, that they hold it impiety to abuse it, either in breaking a branch or otherwise, but contrarily adorne it with Streamers of silk and ribbons of all colours. The Pagods are sundry sorts and resemblances, in such shape as Satan visibly appears unto them: ugly faced, long blackhaire, gogl’d eyes, wide mouth, a forked beard, hornes and stradling, mishapen and horrible, after the old filthy forme of Pan and Priapus.8

To have found the devil and Satan in India was not strange and unusual to the Europeans, as they knew they were there all along. Recent scholarship had tended to stress that European accounts of the peoples of the New World, Africa and Asia, dwelt less on the strangeness of the ‘other’ but rather on their familiarity. The ‘exotic’, writes Michael Ryan, could be fitted into a familiar web of discourse, as they were after all heathens and pagans, and ‘no matter how bizarre and offbeat he appeared the unbaptised exotic was just that — a heathen’.9 When travelling in a strange land, even meeting an old enemy, the devil, is something of a comfort.

Europeans knew the world through its signs and correspondences to things known. The exploration of the terrestrial world was being carried out at the same time that Europeans were exploring their own origins in the pagan past of Greece and Rome. Hence another way of knowing Indians arose through looking for conformities between the living exotics of India and their ancient counterparts in Egypt, Greece and Rome. The exotic and the antique were one and the same.10 Brahmans, yogis and sadhus were ‘gymnosophists’, followers of creators of the Pythagorian ideas about the transmigration of souls. These holy men in their benign mode were naked philosophers who in some medieval European traditions were the symbols of natural goodness ‘who embodies the possibility of salvation without revelation … outside the established Church’.11 The Brahmans and yogis as ‘good’ were to eventually lose out to another reading, and become the perpetrators of superstitions, which they created and manipulated to mystify and keep subordinated the rest of the Hindu population of India. The yogi, the sannyasi, the fakir, the sadhu had by the 18th century been converted into living devils and the followers of all that was lascivious and degenerate in Greek and Roman religion, the worship of Pan and Priapus.

The literature on India of the 17th and early 18th centuries varies in its content but it established an enduring structural relationship between India and the West: Europe was progressive and changing, India static. Here could be found a kind of living fossil bed of the European past, a museum which was to provide Europeans for the next two hundred years a vast field on which to impose their own visions of history. India was found to be the land of oriental despotism, with its cycles of strong but lawless rules, whose inability to create a political order based on anything but unbridled power led inevitably to its own destruction in a war of all against all, leading to anarchy and chaos.

The British, in their construction of the history of India, came into the Indic world at one of its periods of inevitable decay and degeneration into chaos. Through the development of their version of rational despotism, they were able to find and maintain a stable basis for ordering Indian society. Fortunately it turned out that there were enduring and unchanging institutions in India at the local level. The traditional Indian state was epiphenominal and it was found to have no political order, rather India turned out to be a land of unchanging institutions based on family, caste and the village community. The ‘discovery’ of the relationship between the classical languages of Europe, Latin and Greek, and Indian Sanskrit, led to refinement of comparative method. This enabled the Europeans to provide India with a macrohistory organised into developmental ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Plates

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I inaugural formations

- Part II national re-orientations

- Part III contemporary engagements

- About the Editors

- About the Series Editor

- Notes on Contributors