- 428 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Music in the British Provinces, 1690-1914

About this book

The period covered by this volume, roughly from Purcell to Elgar, has traditionally been seen as a dark age in British musical history. Much has been done recently to revise this view, though research still tends to focus on London as the commercial and cultural hub of the British Isles. It is becoming increasingly clear, however, that by the mid-eighteenth century musical activity outside London was highly distinctive in terms of its reach, the way it was organized, and its size, richness, and quality. There was an extraordinary amount of musical activity of all sorts, in provincial theatres and halls, in the amateur orchestras and choirs that developed in most towns of any size, in taverns, and convivial clubs, in parish churches and dissenting chapels, and, of course, in the home. This is the first book to concentrate specifically on musical life in the provinces, bringing together new archival research and offering a fresh perspective on British music of the period. The essays brought together here testify to the vital role played by music in provincial culture, not only in socializing and networking, but in regional economies and rivalries, demographics and class dynamics, religion and identity, education and recreation, and community and the formation of tradition. Most important, perhaps, as our focus shifts from London to the regions, new light is shed on neglected figures and forgotten repertoires, all of them worthy of reconsideration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Music in the British Provinces, 1690-1914 by Peter Holman, Rachel Cowgill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicChapter 1

‘A pretty knot of Musical Friends’: The Ferrar Brothers and a Stamford Music Club in the 1690s1

Bryan White

The second half of the seventeenth century witnessed a significant expansion in the number of clubs and societies in England, at first centred on London and subsequently spreading to provincial cities and towns. A range of associations flourished in the capital, encompassing chartered organizations such as the Royal Society and the Sons of the Clergy, county associations that held annual feasts, and more informal clubs holding frequent meetings and brought together by common interests such as literature or bell-ringing.2 Music played a role in many of these organizations, either as an adornment to annual meetings, such as the anthems that graced the Festival of the Sons of the Clergy from the late 1690s, or as the primary focus of the organization, as was the case of the Society of Gentlemen Lovers of Musick, which met most years between 1683 and 1700, usually at Stationers’ Hall near Ludgate, for the performance of a musical ode in honour of St Cecilia.3 Outside London, only Oxford sustained a significant number of voluntary associations, at least until the Glorious Revolution; and of these several music clubs are known, one of which was active as early as the Commonwealth period.4 From 1688, increasing urbanization and personal wealth, especially amongst the middle classes, spurred what Peter Borsay has described as the ‘English urban renaissance’ in cities and towns throughout the provinces.5 Here, too, music played a prominent role with a great diversity of music societies springing up, especially after the turn of the century.6 These societies tended to be located in cathedral cities, and were supported by local clergy and professional musicians attached to the cathedral music.7 It is somewhat surprising, therefore, to discover that what appears to be the first music club in England outside London or Oxford for which any details exist, is not found in a cathedral city such as Norwich or York, or in a spa town like Bath, which specialized in leisure activities, but rather in the market town of Stamford in Lincolnshire. Here, an organized group of ‘musical friends’, with regular meetings, articles, and subscriptions, and access to the latest in fashionable music, was active in the last decade of the seventeenth century.

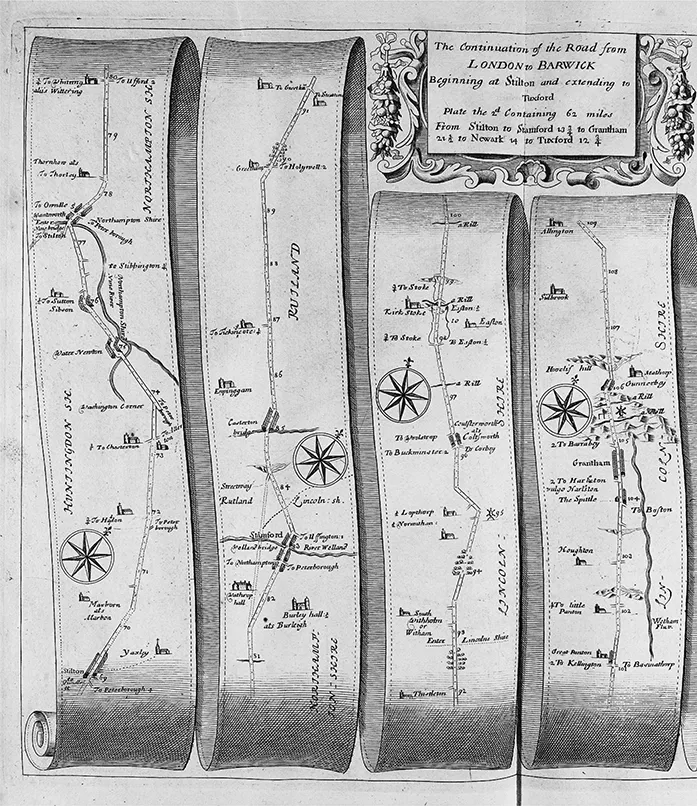

An important textile centre in medieval times, Stamford had declined in significance in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. From about the 1670s, however, the town’s fortunes improved, thanks in part to its position on the Great North Road, 83 miles north of London (see Figure 1.1). ‘The urban renaissance did not bypass Stamford’, as one commentator notes, and it became an important ‘travel town’, benefiting from increased road traffic and improved coach transportation which brought London to just over two days’ journey away.8 Connections with London played an important role in obtaining new music, so that, despite its small size and relative isolation from any professional musical establishment, the town’s music club had the latest fashionable sonatas by Corelli within a few years of their publication in Italy and before they were printed in England. In the last decade of the seventeenth century, Stamford had around 2,500 residents, and, although the music club met in the town, it is not surprising that it found it necessary to draw its membership from the surrounding region rather than Stamford alone. Even by the middle of the eighteenth century, when Stamford had developed a cluster of societies, William Stukeley, founder of the town’s literary Brazen Nose Society, complained of the dearth of suitable members, ‘there being none proper persons in the town, none in the county, neither clergy nor lay in any direction from the place’.9

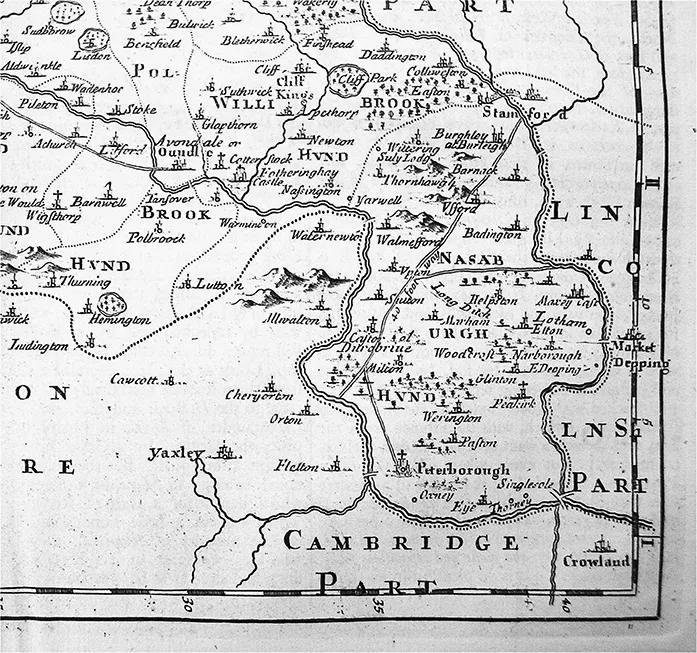

The evidence for the existence of a music club in Stamford in the 1690s is found amongst the Ferrar Papers, a substantial collection of documents of the Ferrar family which was bequeathed to Magdalene College, Cambridge, by the former Master, Peter Peckard, at his death in 1797.10 During the first quarter of the seventeenth century, this family of prosperous merchants was located in London, where they were heavily involved with the Virginia Company until the cancellation of its charter in 1624.11 The following year, the brothers Nicholas (1593–1637) and John (c. 1588–1657) relocated with their families to the isolated manor of Little Gidding in Huntingdonshire, which lies about 15 miles south-southeast of Stamford (see Figure 1.2). There, led by Nicholas, an ordained deacon, they established an Anglican religious household that thrived until the Civil Wars. The Ferrar family received the King at Little Gidding in 1642, and their royalist connections caused them to flee to The Netherlands later that year. They returned sometime around the end of 1645, but without Nicholas’s spiritual leadership, much of his religious and educational programme lapsed. In 1657 John Ferrar II (1630–1720), son of John Ferrar, married Anne Brooke, daughter of the Leicestershire knight, Sir Thomas Brooke, and with her had eight children. The family papers, which span the period 1590–1790, include records of the family business in London, letters, and collections of prints and music, chronicling the activities of the extended Ferrar family living in Little Gidding and beyond.12 Among the papers are a set of ten letters and copies of letters, written between 1693 and 1700, which provide details of musical activity amongst three of the sons of John Ferrar II – Thomas (1663–1739), Basil (1667–1718), and Edward (1671–1730) – and of a group of ‘Musical Friends’ or ‘Cecilians’ meeting in Stamford during this period.13 Thomas was Rector of Little Gidding and of Steeple Gidding during the period of the correspondence (see Figure 1.3). He had attended Pembroke College, Cambridge, from 1679, taking his BA in 1682–83 and MA in 1686.14 Basil was a grocer in Stamford, where he seems to have been living by 1688; by 1702 he was also operating a shop in Oundle.15 Edward was a lawyer living in Huntingdon, though at the beginning of this correspondence he was still in Little Gidding. A discussion of the letters sent to and from the brothers will form the main body of this essay, offering insights into the nature of the music club which met in Stamford, the music it played, and also the domestic music-making of the Ferrar brothers.

Figure 1.1 Detail from John Ogilby’s map of the road from London to Barwick. Stamford is found at mile marker 83. Empingham (Emphingham), the home of Robert Mackworth, is shown a few miles to the west of Stamford. Britannia: or, The Kingdom of England and Dominion of Wales (London, 1698). The plates in this edition are reprints of the 1675 edition. By permission, Special Collections, Leeds University Library

The ten letters that mention musical activities refer to two types of music-making: regular, organized music meetings of the ‘Cecilians’, held in Stamford and focused on instrumental music, especially the music of Corelli; and domestic vocal music, performed by and possibly taking place in the homes of the brothers or their friends. The first letter concerning the Stamford music club is dated 13 January 1693/94, from Basil in Stamford to Edward in Little Gidding [2].16 Basil refers to ‘Our musical friends [who] give their service to you [Edward]’. Although musical references are otherwise absent from the letter, several persons mentioned therein appear in relation to musical business in subsequent letters. ‘Mr: Walburg [who] designs for London on Monday next’ can be identified as Richard Walburge (d. 1715), a successful Stamford grocer.17 He became one of the town’s capital burgesses in 1689, and was elected alderman in 1694 on the payment of £15 ‘for the use of the corporation’.18 He was also an officer for St Michael’s Parish Church in Stamford, serving as churchwarden in 1692 and 1693, and his name appears regularly in the vestry minutes until approximately 1711. Basil was of the same parish; his name, which first appears in the vestry minutes in 1705, when he was chosen as churchwarden, can be found regularly until his death in 1718.19 Like Walburge, he also became a capital burgess of the town, in 1701.20 Walburge served as steward to the Stamford music club in May 1694, and if his trip to London is indicative of regular contact with the capital, he may have been active in procuring music for the club on his journeys. He left a sizable estate at his death, and so may have been in a position to purchase music for the club from his private funds.21 Another member of the circle is referred to in Basil’s postscript as ‘Mr: Beedles’, presumably Revd Henry Bedell (1665–1730), who was probably already active in the Ferrars’ domestic musical activities. Bedell was the Vicar of Southwick, Northamptonshire, which is about ten miles due south of Stamford, and had been a contemporary of Thomas’s at Cambridge, attending Sidney Sussex College from 1681, taking his BA in 1685–86, and his MA in 1689.22

Figure 1.2 Detail from a map of Northamptonshire, by Robert Morden, showing Stamford, Suthwick (Southwick), and Oundle. The top of the map is west. Little Gidding is approximately one mile east of Ludington. Britannia: or, A chorographical description of Great Britain and Ireland […] Written in Latin by William Camden, […] and translated into English, with additions and improvements. Revised, digested, and published, with large additions, by Edmund Gibson, 3rd edn (2 vols, London: R. Ware et al., 1753), vol. 1. The plates in this edition are reprints of the 1695 edition. By permission, Special Collections, Leeds University Library

Figure 1.3 St John’s Church, Little Gidding. In 1634 Edward Lenton described the church as being 40 paces from the manor house. The west front was added in 1714. Photograph © B. White

...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Appendices, Musical Examples, and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations Used in Notes and Contributor Biographies

- Introduction: Centres and Peripheries

- 1 ‘A pretty knot of Musical Friends’: The Ferrar Brothers and a Stamford Music Club in the 1690s1

- 2 Music in the Minster Close: Edward Finch, Valentine Nalson, and William Knight in Early Eighteenth-century York

- 3 A Little Light on Lorenzo Bocchi: An Italian in Edinburgh and Dublin1

- 4 Disputing Choruses in 1760s Halifax: Joah Bates, William Herschel, and the Messiah Club1

- 5 The Role of Gentlemen Amateurs in Subscription Concerts in North-East England during the Eighteenth Century

- 6 The String Quartet in Eighteenth-century Provincial Concert Life

- 7 John Baptist Malchair of Oxford and his Collection of ‘National Music’1

- 8 Music of Rural Byway and Rotten Borough: A Study of Musical Life in Mid-Wiltshire c. 1750–1830

- 9 Mr White, of Leeds

- 10 The Larks of Dean: Amateur Musicians in Northern England

- 11 Finding Themselves: Musical Revolutions in Nineteenth-century Staffordshire

- 12 Lost Luggage: Giovanni Puzzi and the Management of Giovanni Rubini’s Farewell Tour in 1842

- 13 Outside the Cathedral: Samuel Sebastian Wesley, Local Music-Making, and the Provincial Organist in Mid-Nineteenth-century England

- 14 Music for St Cuthbert, ‘Patron Saint of the Faithful North’: The Musical Repertory of St Cuthbert’s Catholic Church, Durham, 1827–1910

- 15 ‘That monstrosity of bricks and mortar’: The Town Hall as a Music Venue in Nineteenth-century Stalybridge

- 16 The Provincial Musical Festival in Nineteenth-century England: A Case Study of Bridlington1

- 17 Educating England: Networks of Programme-Note Provision in the Nineteenth Century1

- Index