- 462 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Music in Wales has long been a neglected area. Scholars have been deterred both by the need for a knowledge of the Welsh language, and by the fact that an oral tradition in Wales persisted far later than in other parts of Britain, resulting in a limited number of sources with conventional notation. Sally Harper provides the first serious study of Welsh music before 1650 and draws on a wide range of sources in Welsh, Latin and English to illuminate early musical practice. This book challenges and refutes two widely held assumptions - that music in Wales before 1650 is impoverished and elusive, and that the extant sources are too obscure and fragmentary to warrant serious study. Harper demonstrates that there is a far wider body of source material than is generally realized, comprising liturgical manuscripts, archival materials, chronicles and retrospective histories, inventories of pieces and players, vernacular poetry and treatises. This book examines three principal areas: the unique tradition of cerdd dant (literally 'the music of the string') for harp and crwth; the Latin liturgy in Wales and its embellishment, and 'Anglicised' sacred and secular materials from c.1580, which show Welsh music mirroring English practice. Taken together, the primary material presented in this book bears witness to a flourishing and distinctive musical tradition of considerable cultural significance, aspects of which have an important impact on wider musical practice beyond Wales.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Music in Welsh Culture Before 1650 by Sally Harper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Sources and Practice of Medieval Cerdd Dant

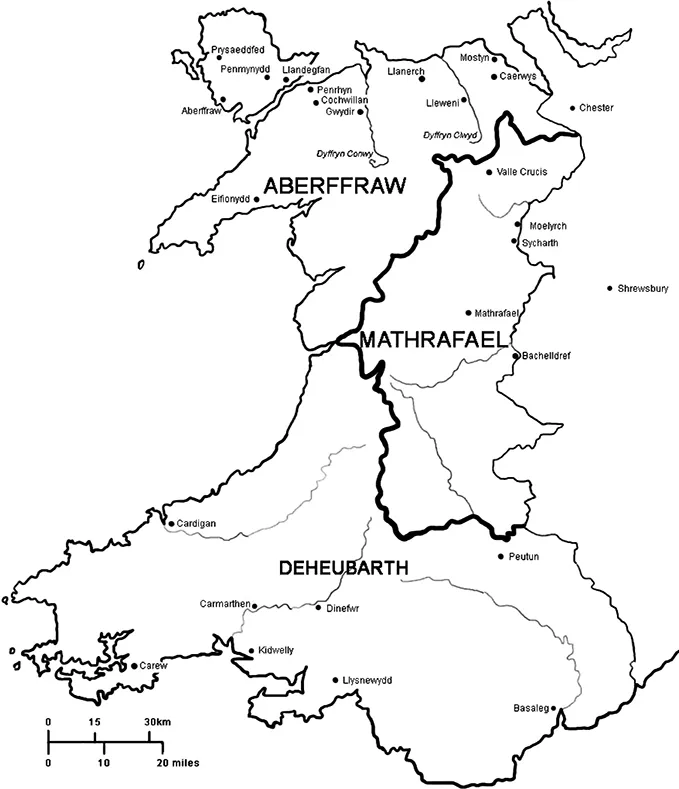

Map 1 Principal locations mentioned in Part I, showing the three late medieval bardic provinces.

Chapter 1

Cerdd DantA Welsh Bardic Craft in Context

The most significant, distinctive, and yet most elusive, music of medieval and early modern Wales is ‘the craft of the string’ or cerdd dant, played on harp and crwth. Its distinctiveness is apparent from the surviving tablature to which some of the repertory was committed in the early seventeenth century (by Robert ap Huw of Anglesey) at a time of retrospective preservation. Its elusiveness is in part due to the oral nature of the craft, and in part results from the social framework and context in which it was made and valued. But there is no doubt that this was an elevated music with a courtly function. It belonged in the households of the Welsh nobility and their princely predecessors, and its status was further underlined by an intimate relationship with Welsh strict-metre poetry, cerdd dafod or ‘the craft of the tongue’. Musicians and poets trained in this sophisticated tradition were regarded as skilled professional craftsmen, and they belonged to a hierarchical bardic order that shared some parallels with the craft guilds of the medieval trades. These bardic practitioners were sometimes referred to collectively as gwŷr wrth gerdd (literally, ‘men at their craft’).

Music and poetry in the noble Welsh household

A vivid picture of the environment in which these related Welsh crafts of string and tongue flourished emerges from the poetry itself. Since the professional bard earned his living in the service of the noble patron, much of the surviving verse sets out to affirm pedigree and status by direct reference to gentility and generosity. Patrons were celebrated in eulogies, elegies, greetings, and in poems that solicit gifts, all delivered in an environment where harp and crwth provided an essential musical framework. A patron’s house - the physical embodiment of his affluence and liberality - was a subject of particular celebration. Dafydd ap Gwilym (fl. 1330-50), that finest of Welsh poets, addressed a series of praise poems to Ifor ap Llywelyn or Ifor Hael (‘the generous’), whose home at Gwernyclepa, near Basaleg in south-east Wales (see Map 1), provided a ready welcome for the bards. Here were gifts of jewels and red gold, the constant flow of wine vessels; a fine floor that echoed with carousing and melody; and an invitation from the host himself to hunt with hawk and hound or to play chess and backgammon.1 A poem of c.1390 by Dafydd’s near contemporary, Iolo Goch (t-.1325-c.1398), is equally warm in its praise of the new home of Owain Glyndwr at Sycharth, not far from Oswestry on the Shropshire border. The epitome of ordered refinement, Sycharth had its own vineyard, mill, bakehouse, fishpond and chapel; white bread was served at table, and its cellars were stocked with best beer from Shrewsbury. Poets and musicians were welcomed here regularly, sometimes in great numbers, and eight of them could be accommodated in four well-lit lofts crowned with tiled gables.2 The house of Dafydd ap Cadwaladr, Bachelldref in eastern mid Wales, was another place of universal welcome.3 ThepoetSypyn Cyfeiliog(fl. 1340-90) exulted in the free-flowing liquor and sweetly-seasoned food served here each Christmas, when noble pedigrees were praised and ‘customary songs sung aloud’ to the sound of the strings (‘A llef gan dannau a llif gwirodau,/ A llafar gerddau gorddyfnedig’);4 Sypyn’s contemporary Lywelyn Goch ap Meurig similarly observed that Bachelldref was a place worthy of the sound of harp and pipes, where money was paid for songs (‘Lle gwir y telir talm dros gerddau,/ Lle teilwng lief telyn aphibau’).5

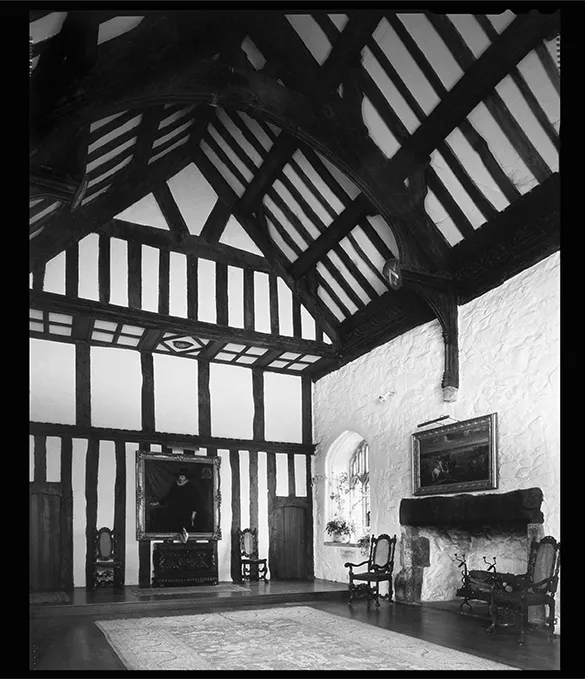

Figure 1.1 The timber-framed hall-house (c.1465) of Cochwillan, near Talybont, Bangor.

The physical focus of an affluent household such as this was its great open hall, designed for feasting, and the remains of several Welsh timber-framed hall-houses surviving from the period 1430—1555 give us an idea of the surroundings in which bardic poetry and music were delivered.6 Typically, the hall was supported by a great central truss (celebrated and described explicitly by a number of poets), and often incorporated a canopied dais, where the owner and his family sat at high table. One of the finest hall-houses to survive is Cochwillan near Talybont, Bangor (Figure 1.1), built around 1465: this was the residence of William ap Gryffydd, who fought for Henry VII at Bosworth and became Sheriff of Caernarfonshire in 1485. Cochwillan was feted by several generations of poets, and Guto’r Glyn (fl.c.1435–c.1493) lavished particular praise on its table and welcoming hearth.7 Larger houses of this type could evidently offer hospitality on a grand scale, and the poet Lewys Glyn Cothi (c.1420–89) describes a feast attended by sixty at the house of Ieuan ap Phylib, constable of Cefn-llys in Radnorshire.8 A still more auspicious event occurred in April 1507 at Carew castle in Pembrokeshire, where the great tournament hosted by Sir Rhys ap Thomas (1449-1525) to celebrate the first anniversary of his reception into the Order of the Garter was allegedly attended by a thousand.9 The welcoming feast, ‘seasoned with diversitie of music’, was held in Carew’s great hall, festooned with Arras cloth and tapestries, while ‘the bardes and prydydd’s [poets] accompanied by the harp’ sang ‘manie a song in commemoration of the virtues and famous achievements of those gentlemen’s ancestors there present’. Sir Rhys’s feast is a further reminder of the symbiotic roles of the professional poet and musician in medieval Wales, and a fine visual representation of harp and crwth (now at Cothele House on the Cornish border) survives from this very family (Figure 1.2).10

Figure 1.2 Welsh carved panel (?c.1510-20) depicting crwth and harp, now at Cothele House, Cornwall.

Some cultured patrons took a particularly active interest in the bardic crafts (as will become apparent in other ways in Chapter 5). Hopcyn ap Sion of Llysnewydd (near Swansea), for instance, a patron of the poet Lewys Glyn Cothi, would ensure that his guests’ glasses were filled, then tune his harp and sing a stanza (pennill), while accompanying himself with some appropriate tune (cainc):

Arfer Hopcyn gofyn gwin

a’i brynu fal y brenin;

canu telyn, Hopcyn hael,

a’i chyweirio’n gloch urael,

canu pennill, myn Cynin,

gan gainc, peri cywain gwin.

Hopcyn’s practice is to ask for wine/ and buy it like the king;/ to play the harp - generous Hopcyn/ - and to tune it as a splendid bell;/ to sing a stanza - by St Cynin -/ to a tune; to cause the garnering of wine.11

Robert ap Maredudd of Eifionydd (near Porthmadog) was also renowned for his hospitality. A cywydd of c.1436 by Rhys Goch Eryri indicates that this household not only welcomed poets and musicians in the venerable bardic tradition, but also delighted in magicians, acrobats and diverse instrumentalists:

Pob crythor ddihepgor ddyn Dilys a phob cerdd delyn;

Pob trwmpls propr hirgorn copr cau,

Pob son pobl, pob swn pibau;

Pob hudol, anfoddol fydd,

Llwm hadl, a phob llamhidydd;

Pob ffidler law draw y dring,

Pob swtr tabwrdd, pob sawtring.

Every crwth player - indispensable, faultless man -/ and every tune on the harp;/ every seemly trumpet with its long, hollow, copper horn,/ every chatter from people, every sound from pipes;/ every conjurer - unseemly he is -/ and every tumbler;/ every fiddler’s hand climbs up yonder,/ every adversary with a drum, every psaltery.12

Other households were nevertheless more discriminating in their tastes, and William ap Morgan, another of Lewys Glyn Co’this patrons, would clearly have no truck with lesser entertainers. These included tinkers, unlicensed ‘dung-heap’ poetasters (kler y dom), and the common minstrel (erestyn) playing on a ‘coarse string’ (crastant), probably a form of three-stringed fiddle derided in several other sources. In this house, only qualified master poets (penceirddiaid) and respectable harp-playing teuluwyr could be sure of their welcome. Indeed, Lewys makes special mention of one particular master-harper, Y Brido, who probably composed three of the pieces in Robert ap Huw’s manuscript (see Table 7.1, pages 138-9):

Penceirddiaid a’i câr lle ymgymharant,

Haid o dinceriaid fyth nis carant;

Teuluwyr a’i câr, darpar cerdd dant,

Erestyn nis câr ef a’i grastant;

Clêr y dom erom heb warant - amlwg,

Ei guwch a’i olwg a ochelant...

Ei glod a draethir gan gildant - Brido

Tra draetho genua, tra dweto dant.

Chief poets love him where they compete with each other,/ a flock of tinkers will never love him;/ teuluwyr love him, providers of harp music,/ a minstrel with his coarse string loves him not;/ the clêr of the dung-heap, who are upon us without a warrant for all to see,/ avoid his frown and his regard/ ... his praise is declared by the upper string - Y Brido/ while the mouth utters, while the string speaks.13

This evident hierarchy of entertainers in medieval Wales, where the superiority of the qualified craftsman was consolidated by his place within the bardic order, is explored in more detail in Chapter 4.

The rise of bardic circuiting (clem)

Prior to Edward I’s invasion and occupation of Wales at the end of the thirteenth century - marked by the defeat of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, last of the Welsh princes, in 1282 - most bards seem to have been attached to a single princely court. Little is known of the music of this period, although these ‘bards of the princes’ (beirddy tywysogion) evidently accompanied themselves on the harp at times, and again their chief function was to sustain the honour and glory of the patron by providing praise poetry. Indeed, a lengthy awdl of c.1213 by Llywarch ap Llywelyn (fl.1145/75-1220), chief court poet to one of the great rulers of the House of Gwynedd, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, refers specifically to praise of this native prince ‘with tongue and string’ (‘can folawd â thafawd a thant’).14

The demise of the princes after 1282 inevitably brought about a sea change for bardic craftsmen. Patronage now passed to the next layer of the social hierarchy, the uchelwyr (literally, ‘the high men’), landowners of good stock, identified by later generations as the gentry. Those who sang in their honour (known as beirdd yr uchelwyr or sometimes cywyddwyr,15 since the cywydd deuair hirion, discussed below, became their staple poetic form) were now forced to ‘circuit’ bet...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Pagr

- List of Maps and Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- A Note on Welsh Pronunciation

- Introduction The Sources of Welsh Music in Context

- Part I: The Sources and Practice of Medieval Cerdd Dant

- Part II: The Latin Liturgy, Its Chant and Embellishment

- Part III: Welsh Music in an English Milieu c.1550–1650

- Appendix of Liturgical Manuscripts

- Bibliography

- Index of Sources

- General Index