- 175 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mapping Jordan Through Two Millennia

About this book

This book shows how travellers and scholars since Roman times have put together their maps of the land east of the River Jordan. It traces the contribution of Roman armies and early Christian pilgrims and medieval European travellers, Crusading armies, learned scholars like Jacob Ziegler, sixteenth-century mapmakers like Mercator and Ortelius, eighteenth-century travellers and savants, and nineteenth-century biblical scholars and explorers like Robinson and Smith, culminating in the late-nineteenth century surveyors working for the Palestine Exploration Fund. This original and valuable book shows, with full illustrations, how maps of the Transjordan region developed through the centuries, and with its detailed tables and bibliography will aid future scholars in further research.The author took part in archaeological excavations and surveys in Jordan, was Associate Professor of Biblical Studies and Fellow at Trinity College Dublin, has published research papers and books on ancient Jordan. John Bartlett was the editor of the Palestine Exploration Quarterly, and until recently was the Chairman of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

WESTERN KNOWLEDGE OF THE

TRANSJORDAN REGION IN THE FIRST

MILLENNIUM AD

SYSTEMATIC EXPLORATION by European scholars of the regions east of the Rift Valley line marked by the upper Jordan river, the Sea of Galilee, the lower Jordan, the Dead Sea and the Wadi Arabah did not begin until the nineteenth century. The work of Seetzen and Burckhardt in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, the travels of Robinson and Smith in the middle of the century, and the surveying work of the Palestine Exploration Fund in the final decades led to the military surveys of the twentieth century and the development of modern mapping, using first aerial photography and then satellite imaging to provide maps of an accuracy unimaginable in earlier centuries. Before the nineteenth and twen tieth centuries, however, mapmakers concentrated on ‘the Holy Land’, drawing their information mainly from the Bible and the classical writers, and until the eighteenth century at least presenting the regions beyond the Jordan mainly in so far as they related to the biblical story.

The first non-biblical information about the lands east of the River Jordan comes from Roman sources. The early third century Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti gives us some place names on a route from Heliopolis (Baalbek) south via Abila, Damascus, Aere, Neve, Capitoliada, Gadara and Scythopolis, but names nowhere south of Scythopolis. The Itinerarium Burdigalense (Bordeaux Pilgrim, a.d. 333) also mentions Scythopolis, but otherwise tells us nothing about Transjordan. (For texts of these itineraries, see Ortelius [1600], and Cuntz [1929].) Much more informative are the late fourth-century–early fifth-century Notitia Dignitatum, ‘list of office-holders’, and the perhaps fourth-century road-map of the Roman empire known as the Tabula Peutingeriana, or Peutinger Table.

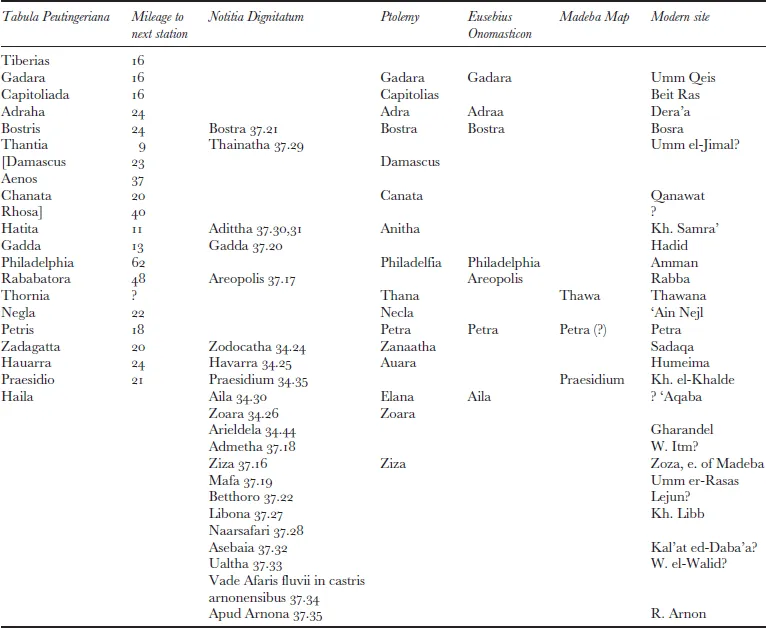

Of the Tabula Peutingeriana (Pl. 1A), discovered c. 1500 by the German poet Konrad Celtes but named after the Augsburg scholar Peutinger to whom he entrusted it for publication, D. F. Graf (1995, 143) comments that ‘It is generally recognised that this medieval manuscript is based on a prototype of an itinerary that dates from the early Roman imperial period’. G. W. Bowersock (1983, 185) believes that the ultimate source was the first-century bc map made by Marcus Agrippa (64/3–12 BC) for Augustus and displayed at Rome in the Porticus Vipsaniae. Whatever its origins, ‘its main purpose was the reproduction of the land routes of the known world between Britannia and Taprobene (Sri Lanka)’ (Zimmermann 2003, 1140). This document is therefore clearly important evidence for knowledge of the routes of the Roman Empire at an early stage of its development. For the Transjordan, this map shows a route starting from Tiberias on the west side of the Lake of Tiberias (Sea of Galilee), crossing eastwards to Bostra, and then running south via Philadelphia (Amman) to Haila on the Gulf of ‘Aqabah. This road is apparently joined at Hatita (Kh. Samra’: Desreumaux and Humber 1981, 35) by a road coming from Damascus in the north, and at or near Rababatora by a road coming from Thamara to the west. At Haila it is met by a road running south across the Negev from Oboda. This map shows the main towns and other stations on the roads, with the distances between them in Roman miles.

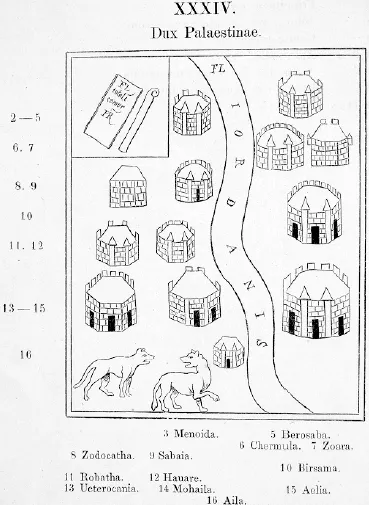

The Notitia Dignitatum is ‘a list, as its name implies, of civilian and military office holders and administration, accompanied by maps of appropriate locations’, dated between 395–413, perhaps with later revision (O. A. W. Dilke 1985, 167–69). The extant manuscripts (held at Oxford, Paris, Munich, Cambridge and Frankfurt) are all comparatively late, from the fifteenth century, probably copied from a tenth-century Codex Spirensis, from Speyer Cathedral (Harley and Woodward 1987, 244–45). The maps ‘seem to have been compiled line by line from the text, by someone who had little topographical knowledge and who inserted place or province names in textual order’, and were possibly ‘invented in the Dark Ages’ (Dilke, ibid.; cf. Harley and Woodward 1987, 244). Many of the place-names west and east of the River Jordan mentioned by the Notitia Dignitatum (Fig. 1) appear also in the Peutinger Table, and between them these documents give some idea of Transjordan as it was known, at least to the Roman military and civil administration, in imperial times, the Tabula Peutingeriana showing the major route through Transjordan (marking the more important towns Bostra, Philadelphia and Petra with a conventional symbol of two towers) and the Notitia Dignitatum listing the main military and administrative centres. The Notitia Dignitatum gives a number of place-names which do not appear on the Peutinger map. The table below lists the places on the Peutinger map’s routes through Transjordan, from north to south, alongside equivalents from the Notitia Dignitatum, and also from Ptolemy (see Ch. 3 below), from Eusebius’ Onomasticon and from the Madeba Map.

The Peutinger map raises some interesting questions. The route from Tiberias travels roughly east via Gadara (Umm Qeis), Capitolias (Beit Rās) and Adraha (Dera’ā) to Bostra (Bosrā), where it turns sharply south-west towards Philadelphia (Amman) via Thantia (Umm el-Jimāl?) and Hatita (Kh. Samrā’). One would expect the road south from Damascus to Philadelphia to meet the road from Tiberias at Bostra, but in fact according to the Peutinger map the road from Damascus is routed via Aenos, Canatha (Qanawāt) and Rhose (between Bostra and Salecah [Salkhad], Bowersock 1983, map page 101). The Peutinger map road from Damascus to Philadelphia seems to have been routed east of Jebel ed-Drūz; the later Roman road across the Leja’ west of Jebel ed-Drūz ‘had not been built at the time of the Peutinger Table’s archetype’ (Bowersock 1983, 177).

FIGURE 1. Illustration from fifteenth-century manuscript of Notitia Dignitatum (Seeck 1876). (The Board of Trinity College, Dublin)

The Tabula Peutingeriana and Eusebius’ Onomasticon present different pictures of the Transjordan. The Peutinger map limits itself to the main routes running through Transjordan. Eusebius mentions the important places on them — Kanatha, Adraa, Bostra, Gadara, Philadelphia, Areopolis, Petra and Aila — but his interest is in the wider range of biblical and ecclesiastical sites, including such places as Pella, Jerash, Madeba, Hesbān, and Kerak. The Peutinger Table draws on imperial administration, and Eusebius on biblical and early Christian writers and on his personal knowledge of the country. The author of the Peutinger map could not have known the region first-hand; for example, he makes a serious geo graphical error by having the River Heromicas (the modern R. Jarmuk) flow into the north-east corner of the Lacus Asphaltidis (Dead Sea) rather than into the Jordan a little south of the Sea of Tiberias. Eusebius, and the author of the Madeba Map (see below), show much more detailed knowledge of the region.

First millennium travellers to Palestine from western Europe (see Wilkinson, 1977) were mainly Christian pilgrims and scholars, such as Paula (AD 382), Theodosius (c. 518), Antoninus Martyr (c. 560–70), the Piacenza Pilgrim (c. 570), Arculf/Adomnan (c. 670), and St Willibald (c. 754). The Piacenza Pilgrim reveals knowledge of Antoninus who ‘preceded’ him (perhaps in a spiritual sense; cf. Wilkinson 1977, 79, n. 2). They have left no maps, but some of them show at least some knowledge of Transjordan, as the following table shows:

| Theodosius | Antoninus M. | Piacenza P. | Arculf | Willibald |

| Bethsaida | Bethsaida Corozain | |||

| Jor & Dan | Jor & Dan Sea of Galilee Gadara Baths of Helias | Jor & Dan Sea of Tiberias Gadara Baths of Elijah | Jor & Dan Sea of Galilee | Jor & Dan |

| Scythopolis | Scythopolis | Scythopolis Livias | ||

| Salamaida (=Kefrein?) hot baths Dead Sea Segor | hot springs Salt Sea Segor Sodom Gomorra | Zoar Sodom | ||

| Sinai Abila [= Ailath] |

These lists, especially those of Antoninus Martyr and the Piacenza Pilgrim, reveal both biblical and genuinely topographical knowledge. Roughly contemporary with them is the Madeba Map, which, though incomplete, reveals a little more of Transjordan in the Byzantine period, naming and locating the following places (see Pl. 1B): Aenon, now Sapsaphas (W. el-Harrār); [Ba]aru (Hammāmāt ez-Zerqā); Therma Kalliroes, the hot springs of Callirhoe (Ain ez-Zāra); [Char]achmoba (Kerak); Bethomarsea also Maiumas (Ain Sāra, below Kerak); Aia (Kh. ‘Ay, 6 km s.w. of Kerak); Tharais (al-’Irāq, 5 km south of Kh. ‘Ay); the river Zared; [the S]alt Sea also Asphalt Lake, [or De]ad Sea; Bela, also Z[oar, now] Zoora; the Deser[t]; to tou agiou L[ot], the sanctuary of Lot; Praesidium (for these identifications, see Donner, 1992). If Donner is correct in identifying three letters MEL(?) as part of a place-name [Ge]mel[a], the map may once have included reference to Petra and Edom (Donner 1982, 188–91; 1992, 41), but though this is possible it is hardly certain from this limited evidence. Donner (as other scholars) notes (1992, 22) that the main literary source for this map was Eusebius’s Onomasticon (c. ad 320, translated into Latin by Jerome c. ad 400); ‘61 of altogether 149 inscriptions of the present fragmentary map are derived directly or indirectly from Eusebius’ Onomasticon’. Of the names above, however, only the Zared, the Dead Sea, Bela/Zoar, and Petra, if admissible, appear to come from Eusebius. Praesidium appears as a Roman station on the route north from Aila to Petra in the Notitia Dignitatum and the Peutinger Table.

As is well known, the sixth-century Madeba Map gives pictorial representations of many of the places named. Thus in Transjordan the map provides illustrations for Calliroe (a bath), Karachmoba (a walled town), Betomarsea/Maiumas (a domed building with side-wings), Aia, Tharais and Zoara (fortresses), and the sanctuary of Lot (a church). Such illustrations appear on other sixth–eighth century mosaics in Jordan (see Piccirillo 1992), notably at the Acropolis Church at Ma’in (built ad 719/20) and at the Church of St Stephen at Umm al-Rasas (Kastron Mepha’a) (ad 756). At Ma’in the church mosaic is bordered with illustrations of named cities; those remaining on the north border are [Charach M]oba, Areopolis, Gadaron (probably...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of maps

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Western knowledge of the Transjordan region in the first millennium AD

- Chapter 2 Medieval scholars, travellers and mapmakers

- Chapter 3 The first printed maps

- Chapter 4 Jacob Ziegler: Quae intus continentur and Terrae Sanctae … Descriptio

- Chapter 5 The sixteenth-century cartographers

- Chapter 6 Seventeenth-century publications

- Chapter 7 John Speed and Thomas Fuller

- Chapter 8 Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century travellers in Transjordan and their maps

- Chapter 9 Nineteenth-century exploration and mapping of Transjordan

- Chapter 10 The triangulation of Transjordan

- Chapter 11 The modern identification of ancient sites

- Bibliography

- Index

- Colour Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mapping Jordan Through Two Millennia by JohnR. Bartlett,John R. Bartlett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.