- 600 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Law of the Sea

About this book

This series brings together the most significant published journal articles in international law as determined by the editors of each volume in the series. The proliferation of law, specialist journals, the increase in international materials and the use of the internet has meant that it is increasingly difficult for students and legal scholars to have access to all the relevant articles. Many valuable older articles are unable to be obtained readily. In addition each volume contains an informative introduction which provides an overview of the subject matter and justification of why the articles were collected. This series contains collections of articles in a manner that is of use for both teaching and research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Law of the Sea by Hugo Caminos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Baselines and the Territorial Sea

[1]

Baseline Delimitations and Maritime Boundaries

LEWIS M. ALEXANDER*

____________________________

The body of rules and regulations for establishing offshore jurisdictional zones involves three types of geographical issues. One type concerns the width of the various zones, a second issue pertains to the seaward and lateral limits of the zones, and the third involves the baselines along the coast from which the breadth of the zones is measured. The question of baselines is related to the physical nature of the coast itself, a phenomenon which varies greatly from place to place throughout the world. Some coasts are rugged and deeply indented; others are smooth and unbroken; still other coasts are the deltas of rivers where the low-water line can change significantly over short periods of time. Coasts may be fringed by islands, rocks or coral reefs. Given the wide variety of physical conditions which exist world wide, it is somewhat surprising that the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (the Convention or the 1982 Convention)1 provides for baseline delimitations along almost all types of coastline in a relatively few articles.

The official baseline along the coast is an important juridical feature of the state. Waters landward of the baseline, such as bays and estuaries, are internal waters of the coastal state; waters seaward of the baseline are the territorial sea and, if claimed, the contiguous zone and the exclusive economic or fisheries zone. The baseline is also used in the delimitation of certain types of maritime boundaries between states with opposite or adjacent coasts.

The regulations for delimiting baselines are contained in articles 5 through 14 of the 1982 Convention,2 and reflect similar articles which appeared in the 1958 Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone.3 Article 5 of the 1982 Convention refers to a “normal” baseline, one that follows the low-water line along the coast except for irregularities, such as bays or river mouths, where straight closing lines may be used.4 Article 7 refers to the special regime of straight baselines for use “[i]n localities where the coastline is deeply indented and cut into, or if there is a fringe of islands along the coast in its immediate vicinity….”5 A third type of baseline is used in the case of archipelagic states, as provided for in article 47 of the Convention.6

Although the articles of the 1982 Convention have received general recognition as having the status of customary international law, certain ambiguities remain in the wording of some provisions. Also, in a number of cases, countries have delimited baselines in ways which appear inconsistent with the Convention provisions, even where such ambiguities do not exist. This article will consider these ambiguities and apparent inconsistencies of action, and then relate baseline conditions to selected maritime boundary situations.

I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF BASELINE PROVISIONS

The problem of baseline delimitations goes back at least four centuries. In 1598, for example, Denmark proclaimed an exclusive fisheries zone eight miles7 in breadth about Iceland;8 in 1604 King James I ordered straight baselines to be drawn between headlands along the British coast, forming 26 “King’s Chambers” which were considered to be British waters.9 In those early years issues of customs and neutrality were important in determining offshore juridical zones. In 1736 Britain adopted the first of its “Hovering Acts,” establishing a customs zone twelve miles in breadth along its coasts;10 nine years later the Danes defined the breadth of their neutrality zone as four miles, again measured from their coastline.11

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries baselines tended to follow the sinuosities of the coast. The problem of bays, however, was seen as a special issue. The Anglo-French Fishing Treaty of 1839 stipulated that bays with entrances ten miles or less in width could be closed off by a straight line at their mouth;12 the breadth of the territorial sea was to be measured seaward of the closing line. The North Seas Fisheries Convention of 1882 for the first time permitted ten-mile closing lines within bays that were more than ten miles across at their mouth, and the closing line was to be drawn as close to the entrance of the bay as possible.13

The first coordinated international attempt to develop rules and regulations for baseline delimitation occurred in the 1920s. In 1924 the Council of the League of Nations appointed a Committee of Experts for the Progressive Codification of International Law.14 One of a series of sub-committees appointed by the Committee concerned territorial waters15 and met in 1925 and in 1926. The sub-committee reports,16 issued in 1926, contained a number of recommendations on delimitation practices that, of course, had no binding effect on coastal states. The recommendations served as a basis for the ensuing multi-national conference.17

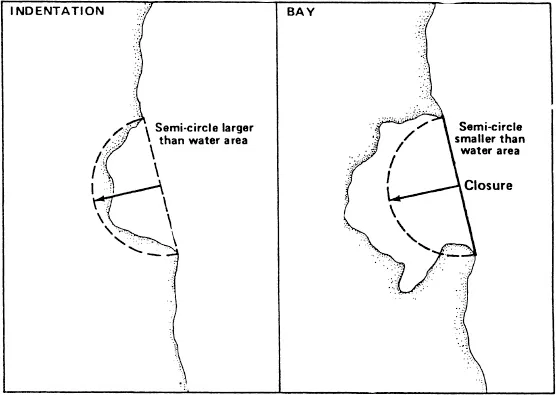

The Second Committee of the 1930 Hague Conference on the Codification of International Law dealt with territorial waters.18 The United States delegation to the Conference presented a series of recommendations;19 one concerned a “semicircle” rule permitting a differentiation between “true” bays and mere indentations in the coast,20 and another recommendation dealt with the “envelope” method of marking the outer limits of the territorial sea.21 The Hague Conference adjourned without formally adopting any of the offshore delimitation proposals.

The issue of “true” (later termed “juridical”) bays had become important prior to, and during, the 1930 Conference. As early as 1839, as noted earlier,22 ten-mile closing lines were permitted for bays, but problems arose in distinguishing indentations having the configuration of a bay from slight curvatures of the coast. In the 1910 North Atlantic Fisheries Arbitration,23 the Permanent Court of Arbitration had addressed the need for differentiations but left unsettled the technique for distinguishing a “true” bay.24

The U.S. delegation’s proposal in the Second Committee of the 1930 Conference contained a suggestion for a “reduced area” semicircle test for identifying bays. The technique was based on the use of a semicircle described on the closing line at the mouth of the bay, whose diameter was equal to one-half the length of the closing line.25 This technique, however, was later abandoned in favor of a full semicircle method, in which the diameter of the circle equals the full length of the closing line (see figure 1). The Committee of Experts adopted the full semicircle method26 which appears as article 7 in the 1958 Convention, and again as article 10 in the 1982 Convention.27

Figure 1. Semi-circle Test for Bay Determination

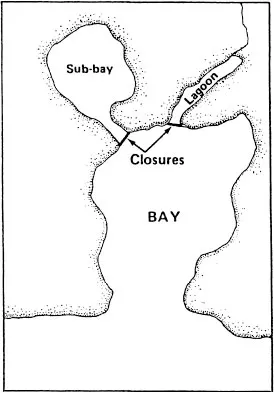

Figure 2. Closure to Eliminate Sub-features

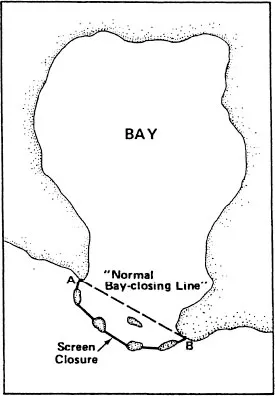

Figure 3. Screening Islands at Mouth of Bay

Source: U.S. Dep’t of State, Office of the Geographer.

During the two decades following the Hague Conference, several scholarly writings appeared concerning baseline delimitations,28 but there were no general international efforts to clarify delimitation issues. In 1947, the United Nations General Assembly established an International Law Commission of 15 international lawyers and jurists.29 At its first session, the Commission selected as initial topics for consideration the regimes of the high seas and the territorial sea.30 Work on the territorial sea began in 1952, based on a report of the special rapporteur, J.P.A. Francois,31 and in 1953 the Committee of Experts met to consider the rapporteur’s findings.32 The following year the Commission circulated provisional articles to governments relating to the territorial sea and the high seas. In 1956, based in part on the replies received, the Commission issued its final report on the regime of the territorial sea and the regime of the high seas.33 These recommendations formed the background for the scheduled Law of the Sea Conference.

The First Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS I) was convened in Geneva in April 1958 with 86 delegations in attendance.34 The Conference adopted four Conventions; all subsequently entered into force. The Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone,35 one of the four, contained ten articles relating to the delimitation of the baseline for the measurement of the breadth of the territorial sea.36 These Convention articles conformed closely with the earlier recommendations of the International Law Commission. The Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone entered into force in 1964, and its provisions have generally been followed by coastal states in baseline delimitations.

The Second Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS II) was ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I Baselines and the Territorial Sea

- PART II Straits

- PART III Islands and Archipelagic States

- PART IV The Exclusive Economic Zone

- PART V The Continental Shelf

- PART VI Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries

- PART VII The High Seas

- PART VIII Fisheries

- PART IX The International Seabed Area

- PART X Land-Locked States

- PART XI The Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment

- PART XII Marine Scientific Research

- PART XIII Maritime Jurisdiction and Enforcement

- PART XIV Military Uses of the Sea

- PART XV Underwater Archeological and Historical Objects

- PART XVI The Polar Regions

- PART XVII Settlement of Disputes

- Name Index