![]()

1

Ancestry and Early Years

I believe that in spite of all the terrible things which are happening in the world today, there exists some mysterious means of mutual understanding amongst men, some straightforward, purely human solidarity which is supra-national, and this exists precisely in the sphere of the most elevated intellectual, aesthetic and - above all -ethical matters ... I myself, for want of a better word, have called this "Europeanism".1

Karol Szymanowski's concept of 'Europeanism' was a symptom of a much broader, essentially humanistic philosophy which sought to reconcile and synthesize all that was of positive value in European thought and culture. For Szymanowski, art only became a significant matter when it abandoned parochial concerns in order to participate in the 'ever increasing reciprocation of interests undoubtedly taking place between the cultured classes of Europe'.2 This attitude did not imply a mere cosmopolitanism or internationalism which required the denial of national or racial origins, but the elevation of raw materials into 'something which the Good European finds sympathetic and beautiful'.3

The tension between Szymanowski's essentially European outlook and local nationalistic concerns led to frequent recriminations. Poles, in Szymanowski's words, remained 'strikingly great and thrillingly good "Poles'", but found it difficult to 'come up to the standards of the average European'.4 The hostility which Szymanowski provoked frequently led him to feel such acute estrangement from the Polish musical establishment and even at times Polish society in general that his sense of 'splendid isolation' became a recurring theme in both his polemical writing and correspondence. He was aware that his critics would have preferred him not to have existed within Poland and Polish musical culture: 'Each word aimed at me seems to complain tearfully and peevishly that with the untimely emergence both of myself and my ideas, drawn from God knows where, I have dared to stir up and disturb the blissfully idyllic Garden of Eden which has existed here for centuries'.5 In short he was a cosmopolitan outsider, an intruder on the Polish musical scene.

In a very real sense Szymanowski was an outsider. He lived permanently in Poland only from the close of 1919 after the loss of the family's Ukrainian estates and properties during the Bolshevik Revolution. Undoubtedly his birth and upbringing several hundred miles to the east of Poland's ethnic frontiers allowed him to view the music of his homeland from a different perspective and contributed to the formation of detached, critical artistic attitudes, hardened still further by a broadly based education and sojourns abroad in the years preceding the First World War.

While he always regarded himself as a good European and avoided simplistic nationalism in his art, Szymanowski also regarded himself as 'patriotic as the next man'6 and indeed the family could lay claim to an impeccable Polish ancestry. Their name was taken from the village of Szyman, situated in the central Polish region of Mazovia, and the earliest records of their existence date from the beginning of the sixteenth century. Several members of the family served in the Sejm, the Polish Parliament, and others held prominent positions, notably bishop, King's emissary and castelan. The Ukrainian branch of the family was established in 1778, during the reign of Stanislaw Augustus, the last King of Poland, when Dominik Szymanowski, brother of Jozef, the poet and King's Chamberlain, married Franciszka Rosciszewska, daughter of Kajetan, the starosta (literally 'foreman') of Rozow. The Rosciszewskis were settled in the Kiev region of the Ukraine, territory which was subject to the Polish crown from the times of the Jagiellon dynasty until the second partition in 1793, and Franciszka's dowry consisted of property some distance from Kiev. These territories, situated on the Eastern fringes of Polish influence, were always regarded as being the 'borderlands' (whether Kresy for Poles or Ukrainnymi for Russians), and the 'distinctive geographical climate, the intermingling of different cultures, social levels, religion and customs (Russian peasants and Polish nobility), but above all, a true ethnic mixture of Tartars, Cossacks, Armenians, Germans and Jews created an unprecedented one-of-a-kind cultural enclave which was referred to as "Kresowa"'.7 While maintaining close contacts with the Mazovian wing of the family, the Ukrainian branch carved out a distinguished niche for themselves in their adopted region. Dominik Szymanowski, the composer's great-great-grandfather, became president of the Kiev Nobility, and his descendents continued to be active in public life throughout the nineteenth century.

The composer's mother was descended from the Barons von Taube, members of the German Teutonic Order associated for centuries with the province of Courland (now Latvia) in Polish Lithuania. Courland was ceded to the Polish King Zygmunt August in 1561, and in 1572 the Taubes were endowed with the rights and privileges of the Polish nobility. By the middle years of the nineteenth century a Russian branch of the family also existed. Three of the six sons of the composer's maternal great-grandfather, Karol Alexander von Taube, became Russified, while the remaining three, Gustav, Karol and Henryk, continued the Polish line, electing at the same time to abandon Lutheran Protestantism for Roman Catholicism.

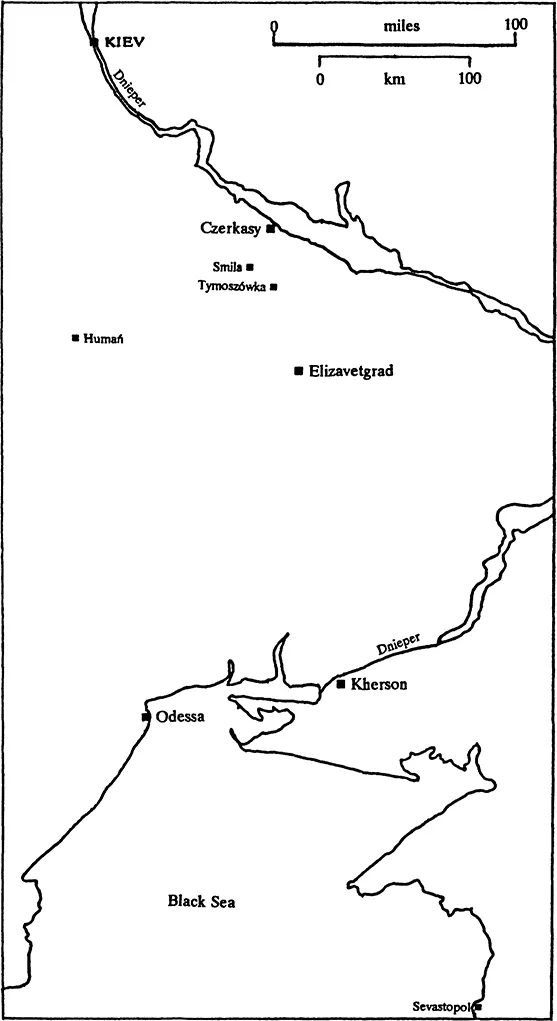

The composer's father, Stanislaw Bonawentura Marian Szymanowski (1842-1905) married Dominika Teodora Anna (1853-1943) in 1874, at the Sitkowiecki Chapel at Sitkowice. At the same time, Stanislaw's brother, Marcin, was married to Jozefa, another of Karol von Taube's daughters. Stanislaw was then living at Orlowka, near Znamionka, a station on the Kiev-Jekaterynoslawska railway line. Four of his five children - Anna, Feliks, Stanislawa and Zofia - were born there, but the third, Karol Maciej Korwin-Szymanowski, was born at Tymoszowka, the family estate then in the possession of Feliks Szymanowski, Karol's grandfather.

For many years confusion surrounded the composer's date of birth. Szymanowski's first biographer, Stanislaw Golachowski, incorrectly recorded it as 6 October 1882 in a monograph first published in 1947. Throughout his adult life, Szymanowski himself maintained that he was born in 1883, an assertion seemingly confirmed by an identity card issued by the Polish Republic in 1920. Other official papers, for example those issued by the Polish military authorities, give the date of birth as 20 January 1883, while his death certificate states it to have been 24 September 1883. But, as Teresa Chylinska finally demonstrated in 1980,8 the true date of birth is reliably established in three separate, unrelated documents. From his baptismal certificate we learn that he was christened according to the rites of the Roman Catholic church in the Smilanska Parish Church by the Reverend Antoni Marciszewski on 21 October 1882 (Russian old style). The date of birth given here is 21 September 1882 (old style), that is 3 October 1882 (new style). This date is confirmed by the document recording his formal registration within the fellowship of the nobility (issued on 5 October 1887) and by a certificate issued on 10 June 1900 by the District School at Elizavetgrad where he sat his final school examinations.

The Tymoszowka estate passed to Karol's father, Stanislaw, in 1889, and it was there that Karol spent his formative years. Tymoszowka itself was situated in the Chekhrin District Authority of the Province of Kiev, and according to the official government description of 1900 consisted of a village with a population of 1 739 inhabitants. Within its boundaries there were two large manor houses, one belonging to the Szymanowskis and the other, facing it across a lake, to the Rosciszewskis. In addition there were 363 farm-holdings, twenty mills, three blacksmiths' forges, a brickyard, a licensed retailer of liquor, and a fire brigade with four appliances. Its nearest railway station was Kamionka, 7 versts away, and the nearest inland landing-stage was Czerkasy on the Dnieper, some 50 versts away. There was one Orthodox and one Uniat church, but as the nearest Roman Catholic church was the distant Smilanska Parish Church at which Karol was christened, it was usual for the priest to travel to Tymoszowka where Mass was celebrated in the library. On these occasions, members of the family were joined by the few other Poles still residing in the immediate vicinity.

The Szymanowski's estate was spacious. The grounds included the lake and an orchard which produced fruit of legendary high quality. The house, which in itself was rather gloomy and apparently not regarded as being attractive, was surrounded by farm buildings and in layout was typical of many Polish manor houses. It was single-storeyed, with a broad corridor running along its length like a spine. It was sheltered on both sides by lindens, and on one side also by two old walnut trees which bore fruit every year. Along almost the entire western side of the house there was a white veranda, densely overgrown with wild vines. Inside it smelt 'a little of fruit, a little of floor-polish, plants, fresh air and old relics'.9 Some of these relics were kept in a Gdansk credenza and chest, and included a dagger, ivory horn and aigrette and brooch which had belonged to King Jan Sobieski (d. 1696), a collection of autographs and the goose quill pen of Klementyna Hoffmanowa, the writer. There were collections of snuff boxes and signet rings, and, on large parchment scrolls, letters conferring public offices on Korwin-Szymanowskis, bearing the signatures and seals of the Kings Wladyslaw IV (1632-48), Augustus the Strong (1697-1733) and Stanislaw Poniatowski (1764-95). Other relics included pistols, swords, a hetman's staff of office with a large topaz set in its head, a cuirassier's suit of armour with a horsehair tassel on the helmet, and old prints on parchment dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Portraits of many ancestors hung on the walls, the oldest of which was of Marcin Korwin-Szymanowski who had served Wladyslaw IV as envoy to Rome in 1634.

In economic and social standing the Szymanowskis were not much different from the other landowning gentry, whether Polish or Russian, residing in the region. They were, however, exceptional in their pursuit of music and the arts in general. For some distant members of the family visiting Tymoszowka there was too much talk of music, but for Bronislaw Gromadzki, a friend and frequent visitor, it was 'an oasis of culture, so elevated, so subtle, in plain words so enthralling, that not only in the Ukraine, but in the most cultured parts of the world, it would have formed an island, different from and superior to the general environment'.10 Karol's father was a man of 'deep musical culture and traditions, inherited from the home of his parents, where Tausig and Liszt had been guests, and where he had heard their masterly playing' (see Plate 2).11 He himself played the piano and cello, and his other interests included natural sciences, astronomy, meteorology and mathematics. Opinions differ concerning his ability to manage the estate, ranging from 'splendid' and 'progressive' (Gromadzki) to the view of Karol's cousin, the poet and novelist Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz, that he was barely competent. He was a retiring man, and preferred to lead a quieter life than his wife, some years his junior, was prepared to allow him, but as long as his health permitted, he took an active part in the games and entertainments organized by his children and their guests, and there were occasions when all the children of the immediate family circle were present at Tymoszowka - not just his own five, but his brother's two, his brother-in-law Karol Taube's six, aunt Helena Kruszynska's two and the three Iwaszkiewicz cousins. He had bitter memories of the Russian repression of the 1863 uprising, and during his lifetime Tymoszowka, 'that patch of land, lost amidst the distant Cossack people, ... a flourishing, tiny island of Polishness in the midst of the rustling sea of wheat in the Ukraine', 12 remained closed to Russian visitors. The one surviving letter to the composer reflects this ardent patriotism, for there he remarked that though he could accept differences of opinion between them 'even on matters of religion', it would be 'most painful' were he to 'discern a lack of love for your country'.13 His youngest daughter, Zofia, believed that his attitudes were fundamentally progressive, and that 'he kept his finger on the pulse of life'.14 He obtained the latest books, and copies of Polish and foreign periodicals were kept in the library. To the end he preserved a cheerful, amiable disposition, even during the final stages of the consumption to which he succumbed. He faced death serenely, receiving the last rites from the priest and then making gentle fun of his scatterbrained sister-in-law, Jozefa, who had been unable to receive communion because she had distractedly drunk a glass of milk: 'A shame ... , my dear Jozia, it tasted of chocolate!'15 Stanislaw was the only one of the family who realized from the earliest days the extent of Karol's genius, and he supported his son unstintingly, acting as his copyist on occasion.

Karol's mother, Anna, seems a less immediately sympathetic character (see Plate 1). Known as 'Madame la Marquise' in certain quarters of the family, she led in an...