- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

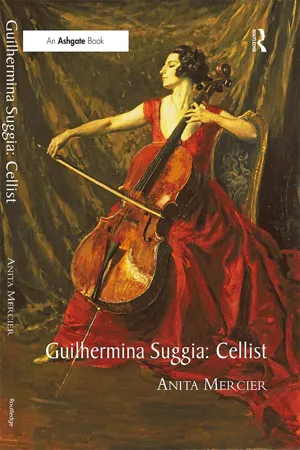

Guilhermina Suggia: Cellist

About this book

Born in 1885 in Porto, Portugal, to a middle-class musical family, Guilhermina Suggia began playing cello at the age of five. A child prodigy, she was already a seasoned performer when she won a scholarship to study with Julius Klengel in Leipzig at the age of sixteen. Suggia lived in Paris with fellow cellist Pablo Casals for several years before World War I, in a professional and personal partnership that was as stormy as it was unconventional. When they separated Suggia moved to London, where she built a spectacularly successful solo career. Suggia's virtuosity and musicianship, along with the magnificent style and stage presence famously captured in Augustus John's portrait, made her one of the most sought-after concert artists of her day. In 1927 she married Dr Jos asimiro Carteado Mena and settled down to a comfortable life divided between Portugal and England. Throughout the 1930s, Suggia remained one of the most respected musicians in Europe. She partnered on stage with many famous instrumentalists and conductors and completed numerous BBC broadcasts. The war years kept her at home in Portugal, where she focused on teaching, but she returned to England directly after the war and resumed performing. When Suggia died in 1950, her will provided for the establishment of several scholarship funds for young cellists, including England's prestigious Suggia Gift. Mercier's study of Suggia's letters and other writings reveal an intelligent, warm and generous character; an artist who was enormously dedicated, knowledgeable and self-disciplined. Suggia was one of the first women to make a career of playing the cello at a time when prejudice against women playing this traditionally 'masculine' instrument was still strong. A role model for many other musicians, she was herself a fearless pioneer.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Guilhermina Suggia: Cellist by Anita Mercier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicChapter 1

Teachers and Mentors

I. Porto

Porto, the ancient “capital of the north,” is the second largest city in Portugal after Lisbon. Famous for its port wine trade, it winds by the thunderous waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the misty Douro River. Guilhermina Augusta Xavier de Medim Suggia was born in Porto on June 27, 1885.1 Her father, Augusto Jorge de Medim Suggia, born in Lisbon on March 11, 1851, was of Spanish and Italian descent. A professional cellist, he played in the orchestra of the Teatro Real de São Carlos and served on the faculty of Lisbon Conservatory before taking a teaching job in Porto in the early 1880s. His wife Elisa, born on November 26, 1850, was also Lisbonese. The first daughter of Augusto and Elisa, Virgínia, was born three years before Guilhermina. Both children inherited their father’s musical abilities. Virginia was a talented pianist and, like Guilhermina, began musical training at a young age. The daily rhythms of the Suggia household were shaped naturally by music.

Augusto began to teach Guilhermina to play the cello in 1890, when she was five years old, at which point the family had moved from Porto to the neighboring town of Matosinhos. Although it made sense for Augusto to want to pass on his expertise as a cellist to one of his children, at the time the cello was an unusual choice for a girl. Custom dictated that if a female were to play an instrument, she must look appealing and never compromise her feminine charm. Clarinets, oboes, and other instruments held in the mouth, which distorted the facial features, were considered unseemly. Brass instruments were too assertive. The piano was a popular choice, as it allowed a woman to sit upright, playing with minimal physical exertion, perhaps even with bare shoulders decorously displayed. Violin was beginning to catch on, even if, as one American writer said, “a violin seems an awkward instrument for a woman, whose well-formed chin was designed by nature for other purposes than to pinch down this instrument into position.”2

The cello and its cousin, the bass viol or viol da gamba, presented obvious problems. Before the 1860s, when the endpin came into use, both of these instruments were held between the knees or calves. “Decency, modesty, and the hoopskirt fashion effectively prohibit the fair sex from playing the viol,” observed the Abbé Carbasus in 1739.3 Even fewer women took up the cello than the viol da gamba, apparently because of the necessity of frequent shifting and greater string resistance. The tonal qualities of the cello reinforced its masculine associations. As the historian W.J. Wasielewski put it, the cello

lends itself far less to virtuoso exaggerations and confusions than does the easily portable violon [sic], so favorably disposed for every variety of unworthy trifling. The masculine character of the cello, better adapted for subjects of serious nature, precludes this … If the violon, with melting soprano and tenor-like voice, speaks to us now with maidenly tenderness, now in clear jubilant tones, the violoncello, grandly moving for the most part in the tenor and bass positions, stirs the soul by its fascinating sonority and its imposing power of intonation.4

Nonetheless, female viol da gamba and cello players were not unheard of. Saint Cecilia, the patron saint of music, was frequently depicted as a gambist. In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Venice, the orchestras of the ospedali conservatories – institutions that trained orphaned and abandoned girls for musical vocations – featured young ladies playing all of the instruments, including the lower strings. There were female gambists in the court of Louis XIV of France. One of the daughters of Louis XV, Henriette, also played the viol da gamba; a portrait of the princess playing her instrument was painted by Jean-Marc Nattier in 1754. Another daughter of Louis XV, Adélaïde, played the cello.

The first woman known to play the cello professionally was a Parisian named Elise Cristiani (or Christiani), who was born on December 24, 1827 and had a short but notable career. She studied with a teacher named Benazet and made a sensational public debut in 1845 at age 17, embarking soon after on a tour of several cities in Germany and Austria. Concertgoers surprised by the novelty of seeing a lady cellist were won over by the beauty of her playing and by her personal charm. (The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung remarked that “the expectation of witnessing an ungainly performance was quite disappointed.”5) Felix Mendelssohn accompanied Cristiani in a concert in Leipzig and dedicated his Song without Words for cello and piano to her. She held an appointment in the royal court of Denmark before succumbing to cholera during a tour in Siberia in late 1853. She owned a Stradivarius cello of 1700 which bears her name.

Cristiani may have contributed to one of the most important developments in cello history: the widespread adoption of the endpin. The endpin was in use as early as the 1600s, but not universally endorsed until the late nineteenth century. Without an endpin, the player was forced to hunch awkwardly over the instrument, whereas the endpin permitted a more relaxed, upright posture and eased the access of the bow to the A and C strings. The tone of the cello also sounded less constricted with the endpin. According to a 1900 article on cello technique, “it has been stated that the tail-pin first came into use on the advent of the first lady ’cellist” [i.e., Cristiani].6 This cannot be completely accurate; Cristiani certainly was not the first cellist to use an endpin, nor are we absolutely sure that she actually used one. On the other hand, some nineteenth-century instructional sources discouraged the use of the endpin on account of its “womanish” associations, which suggests that it was women who led the way with what was to become a standard practice. The endpin transformed cello playing and contributed to the instrument’s evolution as a solo concert instrument.

Even with the endpin, however, many women were taught to hold the cello in ways designed to avoid placing the instrument between their legs. A “side-saddle” position was popular, with both legs turned to the left and the right leg either dropped on a concealed cushion or stool or crossed over the left leg. A frontal position with the right knee bent and behind the cello, rather than gripping its side, was also used. Feminine alternatives like these were still in use in the twentieth century. As late as 1905, the Italian author of an instructional manual remarked that “nelle donne pìu che mai occorre curare la corretta posizione” [“few women play in the correct position”].7

Lisa Cristiani was a novelty at the mid-mark of the nineteenth century. By 1914, Edmund van der Straeten was able to identify over 20 female cellists in Europe and North America, among whom Suggia, May Mukle, and Beatrice Harrison are the most well-known today.8 Most of the women he listed were born in the 1870s and 1880s (Harrison was born in 1892). The growing popularity of the endpin had much to do with the surge in the number of female cellists in the late nineteenth century, but other key changes were also at work. Social conventions that discouraged women from performing in public were relaxing, while at conservatories, women were graduating in record numbers. Barred from employment in all-male symphony orchestras, enterprising women founded their own ensembles, such as the Vienna Women’s Orchestra, proving that they could play all of the instruments just as well as men. Finally, as many of the late Romantic composers discovered the emotional possibilities of the instrument, the repertory for solo cello began to expand significantly. As the turn of the century approached, the appeal of the cello as an instrument of choice was rising for all musicians, including women.

Augusto played the cello with an endpin, so it was natural that the three-quarter size cello ordered from Paris for Guilhermina also had one.9 He taught her to play in the straddle position: a picture of the cellist at age seven shows her sitting comfortably with the miniature cello between her knees. Her older sister Virgínia studied piano with a teacher named Thereze Amaral. The musical progress of the young Suggias was so rapid that before long they began to give public performances at clubs and meeting halls where the local aristocracy gathered for social and cultural events. The first appearance of the prodigiosas was at the Assembly of Matosinhos in 1892. Seven-year-old Guilhermina was described in Porto’s Jornal de Notícias as

dressed in blue, seated in a tiny chair, hugging her cello, reminding us of an enchanting little doll. Her small hands strained to grasp the strings … She smiled and played the bow as if she were playing in her bedroom with a toy. The movement of the bow was strong and secure, very admirable for an age at which the fingers lack the strength and agility that only study and practice will bring with time. Her playing was so astonishing that the ladies and gentlemen got up to cheer her, covering her with kisses which she smilingly acknowledged.10

Between 1892 and 1895, Guilhermina and Virginia gave several joint recitals and became celebrities of sorts in the local salon circuit. Praise was invariably extended to Augusto, the “father and distinguished artist,” who took to the stage for his share of applause at the end of concerts. The success of his daughters fed Augusto’s filial pride and probably enhanced his cachet as a music teacher. A comparison with the hands-on father of another famous child prodigy, Clara Wieck (later Schumann), is called to mind. But unlike Friedrich Wieck, who was tyrannical, possessive and rancorous, Augusto was a genial and affectionate man who put Guilhermina’s interests first. At least until 1904, when she began to tour regularly in Europe and probably became self-supporting, Augusto managed everything necessary for the launching of her career, from bookings and publicity to accompanying her to Leipzig for a 16-month period of study with Julius Klengel. In today’s world, such support might seem unremarkable, the normal performance of a basic parental duty. But in the nineteenth century, it was by no means inevitable that a daughter’s potential would be encouraged by her father, in music or any other field. Violist-composer Rebecca Clarke (1886–1979) and composer Germain Tailleferre (1892–1983) had to struggle with unsupportive fathers, as did the somewhat older composers Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) and Cécile Chaminade (1857–1944). In conservative Catholic Portugal, Augusto Suggia had the vision to imagine futures for both of his daughters outside the boundaries of home and hearth. The foundation for Guilhermina’s ultimate success was laid by her father, who not only recognized her abilities but also supported her ambitions with unstinting devotion.11

It is obvious that Guilhermina’s immediate family was somewhat unconventional. All the same (or perhaps because of it), she had a happy, well-adjusted childhood in a comfortable middle-class home. The only discernible turbulence in her family life relates to tensions between her parents, which became quite pronounced in later life and may have been in the air even when Guilhermina and Virginia were young girls. Of the two parents, Guilhermina was probably more closely identified with and influenced by her father. While Elisa was deeply loved, she appears to have been the less dominant parent; in fact, she was dependent and somewhat helpless, and as the years went by, the necessity of taking care of her fell rather heavily on her younger daughter’s shoulders. It is possible that this early closeness to an encouraging masculine figure accounts for many of the traits that served Guilhermina well in her career, including unapologetic self-confidence and a fierce work ethic. Her teachers and early musical partners were overwhelmingly male (with the exception of Virgínia). In a sense, she grew up in a man’s world and made her way through it with apparent ease. Augusto’s instruction and support, along with the generally happy and stable circumstances of her childhood, undoubtedly had a great deal to do with this.

Abundant opportunities for formative musical experiences in and around Porto also fed the young cellist’s ascent. In the last decades of the century, the city was home to an energetic and innovative community of classical musicians. The leader of this community was the violinist and conductor Bernardo Valentim Moreira de Sá (1853–1924). In the 1870s and 1880s, Moreira de Sá helped found several organizations for the purpose of introducing Porto audiences to music that was familiar in other parts of Europe but scarcely heard in Porto, or in Portugal for that matter. Through performances led by Moreira de Sá, chamber works of composers such as Haydn, Boccherini, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Weber, Schubert, and others were introduced to the Porto musical scene. The capstone of Moreira de Sá’s efforts was the creation of the Orpheon Portuense in 1882. Functioning as both a concert society and a performance venue, the Orpheon Portuense gave musicians and audiences access to a wide range of choral, chamber and symphonic music, with innovative programming featuring both established classics and new works. Ravel’s music was heard for the first time in Portugal when he came to Porto in 1928 at the invitation of the Orpheon Portuense. A 1913 brochure celebrating the history of the Orpheon Portuense lists appearances by a number of the most popular musicians of the day, including Harold Bauer, Ferruccio Busoni, Alfred Cortot, Wanda Landowska, Artur Schnabel, Georges Enesco, Fritz Kreisler, Jacques Thibaud, Eugène Ysayë, and Felix Salmond. The Orpheon Portuense functioned as a de facto music school, with youngsters forming chamber groups and putting on concerts of their own. After her father, Bernardo Moreira de Sá was the most important influence in the first stage of Guilhermina’s musical life. Guilhermina was mentored and encouraged at the Orpheon Portuense, and members of the Moreira de ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Plates

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Teachers and Mentors

- 2 Casals–Suggia

- 3 A New Beginning

- 4 The Lady of the Castle

- 5 Portrait of the Artist

- 6 Turning Point

- 7 Queen of the Cello

- 8 The Final Decade

- Appendix A: Suggia’s Published Writings

- Appendix B: List of Concerts

- Appendix C: “Obituary: Guilhermina Suggia”

- Select List of Sources

- Discography

- Index