![]()

Chapter 1

The Nightingale

Hans Christian Andersen's entrée into Europe's professional music culture began like many of his fictional works did – with a journey. On 4 September 1819, the fourteen-year-old Andersen departed on a two-day trip to Copenhagen after bribing the driver of a mailcoach with three rixdollars to let him ride as a stowaway. Convinced of his talent as a singer and dancer, he was not daunted by the twenty-mile stretch of Baltic Sea that separated him from his destiny, and with just ten rixdollars left in his pocket and a letter of introduction addressed to the Royal Theater's prima ballerina, he was on his way to a life in the theater.

Andersen had already proven himself in the provincial theater life of Odense. As a child, he had enjoyed listening to folk tunes performed by his father and uncle, and he quickly gained a reputation as one of the city's finest young singers.

My beautiful voice drew the attention of other people towards me. My habit on summer evenings was to sit in my parents' tiny garden, which ran down to the river.... Councilor Falbe's garden was next to that of my parents, and nearby was old St. Knud's Church. While the church bells rang in the evening I sat there, lost in curious reverie, watching the mill wheel and singing my improvised songs. The guests in Mr. Falbe's garden often used to listen. (The lady of the house was the famous Miss Beck, who played Ida in Hermann von Unna.) I often sensed the presence of my audience behind the fence, and 1 was flattered. So I became well known; and people began to send for me, 'the little nightingale of Funen,' as they used to call me.1

Andersen's childhood was not an easy one. His father, Hans Andersen, was a struggling shoemaker with an elementary education and a love of fantasy. For a man of his social status, he had a broad knowledge of contemporary literature, and he spent many hours reading aloud to his son from some of his favorite books: Arabian Nights, the fables of Jean de Lafontaine, and the comedies of Ludvig Holberg (1684-1754). Andersen's mother, Anne Marie Andersdatter, was markedly different from her husband. Seven years his senior, she could barely read and could not write at all.2 She took little interest in contemporary literature, yet was fascinated by folklore. Like most mothers, she had complete confidence in her son and strong hopes for his future.

Information concerning Andersen's early education is sketchy. When he returned home at age seven from the local grammar school complaining that he had been struck by a teacher, his mother quickly transferred him to a small Jewish

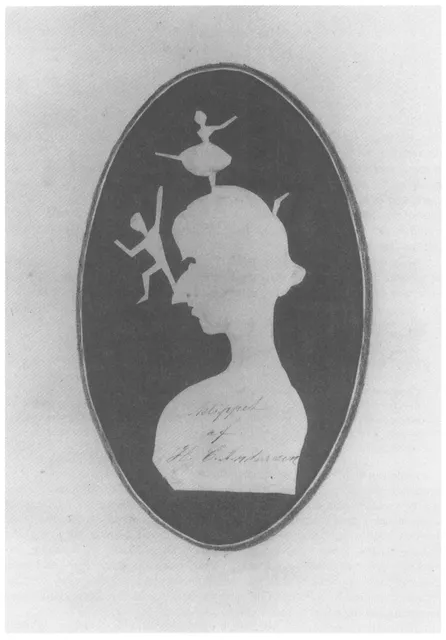

Fig. 1.1 H.C. Andersen. Papercut of Andersen's own silhouette with dancer. (Copenhagen: The Royal Library)

school led by Fedder Carstens. Andersen cherished his time there, for he was warmly received by the other children and encouraged by his teacher.3 But this school was shut down shortly after Andersen's arrival, leaving him no choice but to attend the city's Poor School. Here he was often chastised for not concentrating on his studies, and although he acquired a basic education in reading, writing, and arithmetic, he never learned proper spelling and punctuation.

Though Andersen's autobiographies idealized his family life and childhood years in Odense, the oppression of poverty must have been tremendous. His father had little success as a shoemaker, and in a futile attempt to gain financial stability, he agreed, for a fee, to take the place of a wealthy young landowner who had been drafted to fight in Denmark's war against Russia and Sweden for control of present-day Norway. Hans Andersen departed Odense in 1812 and headed south, but he got no further than Holstein when his health failed him. The promised payment for his services was withdrawn, and he soon returned home ill and spiritually defeated. He died several years later, in 1816.

After her husband's death, Andersen's mother went to work as a washerwoman, and Andersen was sent to work in a local cloth mill. There he entertained the other workers with songs and dramatic performances that soon led to trouble.

I had at that time a remarkably beautiful and high soprano voice that I kept until age fifteen. I knew that people liked to hear me sing; and when someone at the mill asked me if I knew any songs, I immediately began to sing, and this gave great pleasure; the other boys were told to do my work. After I had sung, I told [them] that I could also perform comedies; I remembered entire scenes from Holberg and Shakespeare, and I recited them. The workers and wives kindly nodded at me, cheered, and clapped their hands. In this way I found the first days in the mill very entertaining. One day, however, when I was in my best singing vein, and everyone commented on the brilliancy of my voice, one of the workers cried out: 'That is definitely no boy, but a little maiden!' He seized hold of me. I cried and screamed. The other workers thought it very amusing, and held me fast by my arms and legs. I cried out at the top of my voice and, bashful as a girl, rushed from the building and home to my mother, who quickly promised me that I would never have to go there again.4

Money was still in short supply, however, and Andersen needed to contribute to the family income. A second job was found for him, this time in a local tobacco factory.

Here my voice also made me a success; people came into the factory to hear me sing, and yet the funny thing was that I did not know a single song properly, but improvised both the text and the tune, and both were complicated and difficult. 'He ought to be on the stage,' they all said, and I began to get ideas of that kind.5

At first sight, Odense, with its brightly painted row houses, winding streets, and small squares, seemed a typical Danish country town. Even though it was the second-largest city in Denmark – Copenhagen being the first – and the capital of Funen, its population never exceeded six thousand during Andersen's adolescence. The Crown Prince had a summer residence in Odense, and his occasional presence led to the addition of several cosmopolitan elements to the city, the most prominent being a theater (fig. 1.2). Built in 1795, this simple, nondescript building served as a performance space for theater troupes from Germany and a summer stage for a touring company from Copenhagen's Royal Theater; it was in this theater that Andersen saw his first theatrical performances, a German singspiel by K.F. Hensler and Ferdinand Kauer called Das Donauweibchen (The Little Lady of the Danube) and a German version of Holberg's comedy Den politiske Kandestøber (The Political Tinker).6 Andersen was seven years old when he saw these works,7 and as he later explained, they had a profound effect on his interest in the theater:

From the day I saw the first play my whole soul was on fire with this art. I still recall how I could sit for days all alone before the mirror, an apron around my shoulders instead of a knight's cloak, acting out Das Donauweibchen, in German, though I barely knew five German words. I soon learned entire Danish plays by heart.8

Andersen made friends with the theater manager, Peter Junker, who let him have a theater program from each performance in exchange for help in giving them out; 'with this I seated myself in the comer and imagined an entire play, according to the name of the piece and the characters in it. This was my first conscious effort towards poetic composition.'9

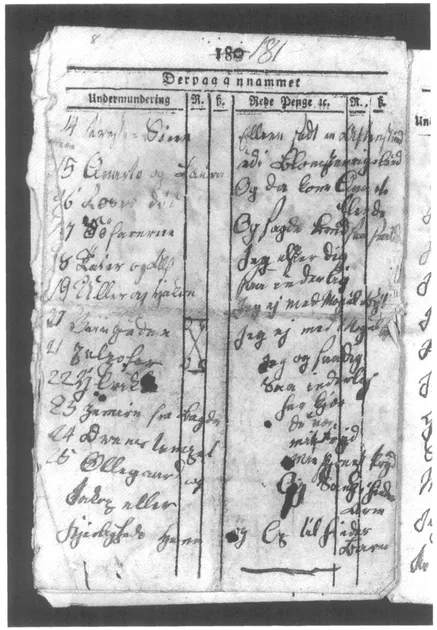

Evidence of Andersen's growing interest in the theater is preserved in the back of an account book that his father bought when he joined the army. Since his father had little use for the journal after returning home, he apparently turned it over to his son, who promptly began using it as a sketchbook for creative ideas10 (fig. 1.3). Andersen recorded his first entry in 1813, a short poem called 'Yes, I Sing,' a clear testament to his early identity as a musician.

Yes, I sing and use vibrato.

Yes, I can play like a musician,

I sing Ut, re, mi, fa, Sol.

I modulate in major and minor.

I can bray like a donkey.

In the land no one can match me.

I sing bass, descant, and tenor.

Yes, a virtuoso stands before you.

Ja jeg synge gjør Tremulanter;

Ja jeg kan spille som en Musikanter;

Jeg synger Ut re mi fa Sol;

Jeg modulere i Dur og Mol;

Jeg som Æsel kan skrige;

I Egnen findes ei min Lige.

Jeg synger Bas Decan Tenor;

Ja en Virtuos til Mand du for.11

Fig. 1.2 Hans Andersen's account book with H.C. Andersen's first attempts at creative writing. (Copenhagen: The Royal Library)

Fig. 1.3 Lithograph of Odense Theater (ca. 1840). (Odense: The Andersen House Museum)

Also preserved in this sketchbook is a list of titles for twenty-five projected dramatic works. No trace of these works now exists, but it is nonetheless interesting to see that as a youth, Andersen was already making plans for a future in the theater.

Andersen's connection to Odense's seasonal theater culture continued throughout his adolescent years. In the summer of 1818, he was even allowed to go back stage during performances and socialize with actors visiting from the Royal Theater.

My child-like manners and my enthusiasm amused them; they spoke kindly to me, and I looked up to them as to earthly divinities. Everything that I had previously been told about my musical voice and my recitation of poetry became intelligible to me. It was the theater for which I was born; it was there that I should become a famous man, and for that reason Copenhagen was the goal of my endeavors.12

His enthusiasm that summer led to a walk-on part as a page in Nicolo Isouard and Charles Guillaume Etienne's opéra-comique Cendrillon,13 an honor that he took seriously: 'I was always the first out there, put on the red silk costume, spoke my line, and believed that the whole audience thought only of me.'14 After his première, Andersen's talents quickly became known among the city's elite:

I was called to their houses, and the peculiar characteristics of my imagination excited their interest. Among others who noticed me was Colonel Høegh-Guldberg, who with his family showed me the kindest sympathy; so much so, indeed, that he introduced me to Prince Christian, afterward King Christian VIII.15

Andersen also came in contact with Christian Iversen, a wealthy printer who was rumored to have strong contacts with the elite of Copenhagen's theater society. Andersen was intent on moving to the capital, but he knew he would need a letter of introduction if he hoped to make it at the Royal Theater. The actors in the traveling company told him that the 'queen' of Copenhagen's theater world was Anna Margrethe Schall, the Royal Theater's prima ballerina. Convinced that only a letter to Schall would do, Andersen harangued Iversen relentlessly: '[Iversen] confessed that he was not personally acquainted with the dancer; nonetheless, he agreed to give me a letter to her.'16

But Andersen needed more than a letter if he hoped to move to Copenhagen. He needed money, and in 1819 he gave numerous impromptu performances in the homes of Odense's elite in an effort to raise funds. Andersen's presentations must have been quite a sight. A first-hand description of one performance, preserved in the diary of a young girl named Ottilie Christensen, gives us a sense of Andersen's frenetic impromptu style:

Master Comedy-Player arrived at dusk ... and for two whole hours the little gentleman played parts from various comedies and tragedies. As a rule, he did well; but we were much amused whether he succeeded or not. The light-hearted parts were the best; but it was most absurd to watch him doing the part of the sentimental lover, kneeling down or fainting, because just then his large feet did not look their very best. Well, perhaps they can improve their style in Copenhagen. Perhaps in time he will make his appearance as a great man on the stage. In the evening we had sandwiches and red fruit jelly; our actor joined us, but in hot haste so as not to lose any time parading his talent. At half-past ten the bishop's wife thanked him for coming, and he went home.17

Two days later, Andersen left for Copenhagen, arriving in the capital on 6 September. When he first set foot in the city, he was struck by the lively atmosphere: 'The whole city was in commotion, everybody was in the streets. But all this noise and turmoil did not surprise me – it corresponded to the commotion I had imagined must always exist in Copenhagen, the capital of my world.'18 Unbeknownst to Andersen, the commotion that surrounded him was not typical, but, rather, the result of a violent pogrom against the city's Jews that had broken out just two days before19 (fig. 1.4). Order had not yet been restored when Andersen arrived, and one can only imagine how the throbbing, unruly crowds invigorated the young man. All around him windows were smashed and storefronts burned. At night, the sounds of gunshots rang through the streets intermittently. 'All the people were greatly animated, like blood in the veins during a fever sickness.'20

Upon entering the city, Andersen's first order of business was a visit to the Royal Theater, a graceful, neo-classical building in Kongens Nytorv, a fashionable square in the center of Copenhagen (fig. 1.5). 'I walked around [the theater], looked at it from all sides, and made a heartfelt plea to God: "Let me enter in here and become a good actor."'21 As Andersen admired the building, a crowd gathered outside the entrance in search of inexpensive tickets for that evening's performance. Hawkers were there as well, and when one approached Andersen and asked if he would like a ticket, 'I did n...