eBook - ePub

Gender, Culture, and Performance

Marathi Theatre and Cinema before Independence

- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book presents a lucid, comprehensive, and entertaining narrative of culture and society in late 19th- and early 20th-century Maharashtra through a perceptive study of its theatre and cinema. An intellectual tour de force, it will be invaluable to scholars and researchers of modern Indian history, theatre and film studies, cultural studies, sociology, gender studies as well as the interested general reader.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender, Culture, and Performance by Meera Kosambi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE: THEATRE

Section I

PHASES OF EVOLUTION

1

Vishnudas Bhave’s Stylised Mythologicals (1843)

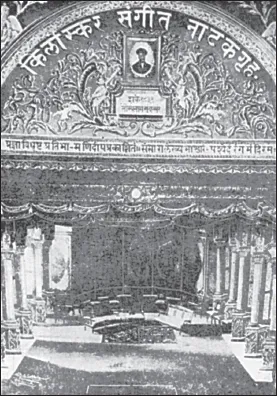

The magnetism of Vishnudas’s mythological plays is captured in journalist–playwright and politician N.C. Kelkar’s childhood reminiscences of the 1880s when he had watched wide-eyed the conflict of good and evil unfold through a clash of devas (gods) and rakshasas (demons). This was at the mansion of the prince of Miraj, where the main audience sat on chairs and benches in the sunken (40×40 feet) courtyard facing the ‘stage’ — one side of the surrounding raised corridor equipped with a cloth curtain — while the other three sides formed the ‘pit’. Nostalgia for a lost age of innocence underlines his humorously evocative Marathi description of the night-long event:

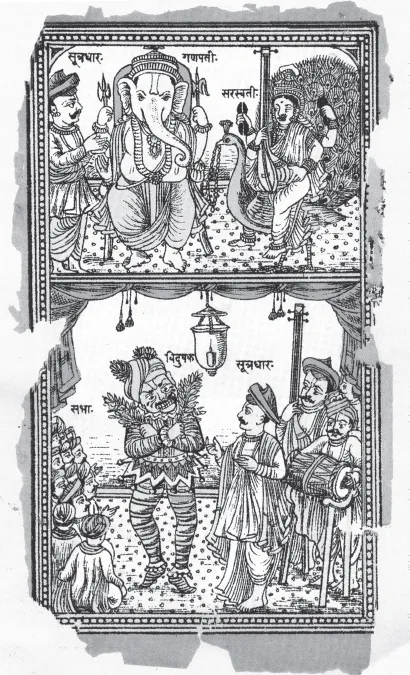

The spatial constraint led to such a blending of actors and spectators that when Saraswati entered, [seemingly] seated on a peacock and dancing around waving handkerchiefs in both hands, the spectators who received her kicks realized that the peacock had no claws but human feet! But even the spectators lacking in proper respect for Goddess Saraswati moved back to make room for the rakshasas about to enter — because they frequently wielded real swords! The four-foot wide passage adjoining the main gate was used by both the spectators and the actors emerging from the ‘green room’ in make-up. This frequently led to a confused crowding, in that narrow passage, of the denizens of all three worlds — heaven, netherworld, and the mortal world! The passage was usually closed to spectators when the rakshasas were to enter, because their entry was like a lioness delivering her first litter of cubs! The curtain would be pulled aside to let them out, flanked by burning torches containing a combustible substance that produced tall flames. Surrounded by these roaring sheets of flame, each rakshas moved back and forth four times and finally made his entry with great effort, roaring like a caged tiger or lion and flashing his sword. Often a whole troupe of rakshasas was to enter, and their entry through this passage took as long as fifteen minutes. The poor devas were meek. They pushed aside the curtain themselves to enter; and if Vidushak was not at hand to offer them seats, they pulled up seats themselves and sat down!1

Even in this august company, Vidushak made a distinctive visual and verbal impression. Dressed in ill-matched pieces of cloth like latter-day circus clowns, he carried on his head a large bundle of neem twigs whose leaves covered his face. On concluding his silly preliminaries with Sutradhar, he put down the bundle to reveal his face painted in stripes. Mainly responsible for jokes and humour, he also performed tasks such as offering seats to the newly-entered characters in keeping with their status, rendering whatever help was necessary, offering advice when asked — or even unasked — and carrying on a dialogue with Sutradhar to provide links between disjointed scenes. Dramatic convention allowed him to be present in every scene, whether it featured gods, demons, or mortals, posing as a denizen of that particular world, and smoothing things over.

But pivotal to the functioning of these spectacular personages was Sutradhar, the play’s mainstay, monopolising the sung narrative to advance the action which the characters mimed. Both the male characters and females (who spoke in a thin sweet voice) paused at the appropriate juncture, saying grandly ‘Lend me your ears’ — and Sutradhar belted out a song in his thick and hoarse voice, clanging the cymbals, after which resumed the action and minimal dialogue.2 The seeming artificiality of Sutradhar singing in the background throughout the show is mitigated by theatre critic Banahatti’s insistence on its main advantage: other action — such as verbal skirmishes, physical combat, and later on, specially introduced dances — could occur simultaneously on the stage. This contrasted with the later musicals when one character sang and the others stood idly by, trying to conceal their boredom.3

At the same historical moment, in the coastal town of Ratnagiri, west of Miraj across the massive Sahyadrian range, novelist–playwright B.V. Varerkar had watched his first play — inevitably a mythological as well. In contrast to the adult Kelkar’s tongue-in-cheek account of his boyhood experience, Varerkar retrieves the spirit of his early emotional response. The five-year-old had been carried by his mother on her hip up a rickety bamboo ladder to the ‘women’s gallery’ in a makeshift theatre walled with dry, mud-plastered coconut leaves — an equivalent of the European ‘fit-in’ theatre made of wooden boards. The boy had sat in her lap spellbound all night, retaining a vivid memory of a sword fight. A succession of similar plays with which his father regaled him left a mixed impression: Ganesh speaking in a human voice and Saraswati dancing on a peacock strengthened his religious fervour, but the roaring rakshasas engulfed in flames filled him with terror which he gradually overcame because of Vidushak’s free and easy interaction with them.4

Total identification with stage characters came easily to children, but their reactions were unpredictable. In the early 1900s, the actor Nanasaheb Chapekar had sobbed his heart out as a child during the tragic mythological play Harishchandra at Pune, as had little Varerkar.5 But about the same time, the same play elicited a very different response from their contemporary P.K. Atre (later humorist and playwright) at the nearby small town of Saswad. Being tickled by Vidushak’s witty sally with Saraswati in the prologue, he laughed uncontrollably through the tragedy which was ‘dripping with the sentiment of compassion’ as if it were a farce, much to the annoyance of his neighbours, until he fell into an exhausted sleep.6

This ubiquity and popularity of shared experiences explain Vishnudas’s title: ‘Bharat Muni of Marathi drama’. His revolutionary innovation presented ‘the first non-traditional, non-folk, non-ritualistic dramatic performance in Marathi’ in 1843, to quote theatre critic Shanta Gokhale.7 However, it remained strongly religious in nature and imbricated at many points with the prevalent traditional, folk, and ritualistic performances.

Vishnudas’s ground-breaking achievement was ‘the generation of a new performative public sphere’ retaining continuity with the existing religious–cultural flows.8 He and his successors are further credited with having shaped this public sphere as secular but also ennobling, didactic but also entertaining, and with disseminating knowledge about the sacred texts known as puranas.9 His new idiom conflated the kirtan-performer’s akhyan (akin to a libretto) with selected Sanskrit dramatic conventions, attiring the core requirements of drama in the popular and respectable garb of sacred stories. But when his collection of ‘dramatic poems’ was published — as late as 1885 — he was only too willing to emphasise his pioneering role (in his partly autobiographical preface) and locate himself within the classical Sanskrit dramatic tradition.10 He valorises the play (natak) as the best type of entertainment, because it combines recreation with moral instruction, excellent speeches, and interesting events replete with rasas and accompanied by song and dance. (The original term for his performances was not ‘natak’ but the generic ‘Ramavatar’ — broadly the legends of Ram.) Rather nationalistically he insists that the dramatic art originated in ancient India and spread to other countries, although the classical Sanskrit dramas and dramaturgical texts were lost through the vagaries of history. In conclusion he underscores his own reclaiming of the lost classical tradition.

Vishnudas’s Revolution in Entertainment

Vishnudas’s life spanned eventful political and cultural transitions. He was born immediately after the end of the Peshwai (probably in 1819) — when popular entertainment was either crudely religious or erotic — and died at the age of about 82 in 1901 during high imperialism when the hugely popular musical plays had practically wiped out his brand of stylised mythologicals.

His family tree reads like a chart of Maratha history.11 His Brahmin forefathers had served Maratha chiefs including the Peshwa. His grandfather later joined the army of the Peshwa’s Brahmin sardar, Patwardhan, who reverted to his family estate of Sangli (part of the original estate of Miraj). His father trained Patwardhan’s infantry and cavalry along modern British lines.

Vishnu Amrit (alias Vishnudas) Bhave was an unruly child; having incurred his father’s wrath at a young age, he was raised by his maternal grandparents in north Karnataka. He studied Sanskrit, mastered the requisite Brahmin prayers and rituals, and learned Kannada. At 12 he returned to Sangli and, after a brief stint in school, devoted himself to classical Hindustani music under the court musician. This was the post-Peshwa period of peace, prosperity, and enjoyment, with a great deal of music, dancing and tamashas, all of which young Vishnudas eagerly consumed. He attracted Patwardhan’s patronage through skills ranging from sculpting clay figurines to composing and narrating mythological stories as daily entertainment.

A fresh impulse to his creativity was the yakshagan performances of a visiting troupe from Karnataka at the Sangli court in 1842. Patwardhan instructed him to create a similar but improved Marathi version, promising all help. Vishnudas, in his early 20s at the time (although he and his biographer grandson claim he was below 20) started his preparations.

The task of composing the play was facilitated by the vast existing pool of mythology, the provenance of all folk entertainment. Vishnudas composed his own akhyan and set it to raga tunes. His unacknowledged debt to existing compositions has been traced by literary critics.12 The issue is not his borrowing, but his innovation and the continuity of the cultural tradition.

A troupe of actors was assembled, using Patwardhan’s offer of a few young men; Vishnudas advertised for more by promising lucrative state jobs and awards. He dispatched assistants to discover young, talented boys in Konkan, the traditional home of dashavatar performances. Such boys were needed for female roles, respectable women being banned as entertainers. Sometimes grown men (who were required to keep a moustache) impersonated women by pasting a piece of paper over the moustache, or half covering the face; after all, realism was not an overriding concern. This practice gradually declined after 1875.13 (P.K. Atre rec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Plates

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One: Theatre

- Part Two: Cinema

- References

- About the Author

- Index