eBook - ePub

Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics

Volume 2: Job Design and Product Design

- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is the second of two edited volumes from an international group of researchers and specialists, which together comprise the edited proceedings of the First International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics, organized by Cranfield College of Aeronautics at Stratford-upon-Avon, England in October 1996. The applications areas include aerospace and other transportation, human-computer interaction, process control and training technology. Topics addressed include: the design of control and display systems; human perception, error, reliability, information processing, and human perception, error, reliability, information processing, and awareness, skill acquisition and retention; techniques for evaluating human-machine systems and the physiological correlates of performance. While Volume one is more clearly focused on the domain of aviation and ground transportation, Volume two is concerned with human factors in job and product design, the basics of decision making and training, with relevance to all industrial domains. Part one opens with a keynote chapter by Ken Eason. It is followed by Part two dealing with learning and training, while Part three reflects the rapidly growing area of medical ergonomics. Part four entitled 'Applied Cognitive Psychology' is biased towards human capabilities, an understanding of which is central to sound human engineering decisions. Part five firmly emphasizes equipment rather than its human operators.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics by Don Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

JOB DESIGN AND ANALYSIS

1 Inventing the future: Collaborative design of socio-technical systems

Abstract

Information technology is transforming work and has many implications for organisations and people at work. It is increasingly common for people at work to be given the opportunity to contribute to the development of future work systems by making early evaluations of socio-technical systems options. This paper discusses the difficulties that people have in making effective contributions to future planning and identifies some of the cognitive processes involved. It presents a range of ways that have been found in practice to help people make an effective contribution. These include the creation of realistic and concrete socio-technical systems scenarios, the engagement of people in role play exercises in the scenarios and the systematic review of implications from stakeholder perspectives.

The challenge of change

One of the greatest challenges facing engineering psychologists and ergonomists is the pace of change in the world of work. A particular force for change is the impact of information technology and the creation of the information society. We are moving rapidly towards a world in which work is characterised by networking, teleworking, virtual teams, automation, outsourcing, globalisation etc. These changes transform the tasks that people undertake and the way they undertake them. For the optimists the world of work will be one of empowerment; when we have the knowledge of the world at our fingertips, enormous processing power and the opportunity to communicate with anyone, anywhere. For the pessimists it will mean a world of separation from the real work materials (because we are dealing with a virtual world), isolation from our fellows, a lack of privacy and a lack of personal control of our lives.

Whatever our views of these great trends they do constitute enormous forces for change. For many organisations and the people who work in them these forces are opportunities and threats – opportunities for new forms of business, threats that they will be left behind by their competitors, opportunities for new careers for staff, fears they may not be able to cope etc. But the information revolution is not deterministic; there are many ways of applying the technology and changing the world of work. This means that organisations and their staff have many choices and could select outcomes in their best interests. Many people are now being given opportunities to help choose future work systems. This is a wonderful opportunity to shape the future for human effectiveness and human well being. But how are they to undertake this task and can we help? Detailed analysis of current work practices may help but the future will be significantly different. How to we help invent the future?

In the HUSAT Research Institute we have assisted many organisations to develop future work systems. Most of these engagements have been within an organisational frame of reference – developing future socio-technical systems – and most have involved a social process in which human actors have evaluated future options. To be effective in this process we have to manage the cognitive processes of the human factors. The aim of this paper is to describe the process by which future systems are being developed and then to identify the cognitive issues which we need to address.

The process of scenario development and evaluation

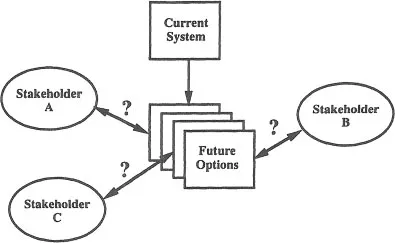

The majority of change processes consist of technical innovations in order to achieve business objectives. There is usually very little analysis of the human or organisational implications and, as a result, implementation is often followed by the realisation of significant implications which may limit the effectiveness of the change. Figure 1 provides a description of a process by which an organisation might examine the opportunities for change and assess the human and organisational implications very early in the process (Eason, 1988; Eason and Olphert, 1996) in order to select the most effective route forward. In this approach the application of new technology to an existing work system is used to construct a number of different scenarios for the future. Each of these scenarios is evaluated by the stakeholders who would be affected by the implementation of the scenario.

The aim in this process is to use the knowledge and insights of the stakeholders to predict the implications of each scenario. Since different stockholders will adopt different attitudes to the strengths and weaknesses of each scenario as it affects their own interests, a rounded picture of the likely human and organisational implications can be developed.

Figure 1 Stakeholder implications of future systems

This approach is part of a general movement to adopt scenario-based design as a means of achieving human-centred design. In most examples of this approach (see Carroll, 1995) the scenario is a technical prototype and the evaluation is an assessment of usability or individual task performance. In this instance the scenario is a broader vision, encompassing not only the future technical system but also the network of human roles that uses it within a business process.

An example of a socio-technical systems scenario evaluation

A case study will illustrate the need for a process of evaluating socio-technical scenarios. We recently assisted a national freight forwarding company in the implementation of a major computer system. The company had a network of branches across the country each exporting and importing goods on behalf of local clients. The aim of the computer system was to provide an electronic means of capturing the details of the freight to be transported which could then be used to create the multitude of documents to serve shipping, trucking, insurance, customer, customs and excise and accounting needs. The company were interested in two scenarios for the application of this system. In the first scenario each branch would be independent and would use the system to undertake its business quite separately from other branches. In the second scenario the data base of planned freight movements could be shared between branches in the same region and they could seek load consolidation – sending loads for different clients going to the same destination together to reduce trucking and shipping costs.

In this instance the company introduced the computer system as a pilot in one region and tried both scenarios. The load consolidation approach met some important business objectives but proved to have a number of serious organisational implications. It meant that branch managers had to co-operate or rely on a regional load consolidator to identify appropriate loads and arrange the transport. In both cases Branch managers lost control of some of their business. Traditionally in this company they had complete control to make deals with local companies and a large part of their income was dependent upon their success. At the end of the trial the company decided that they had to preserve this entrepreneurial spirit which was the basis of the energy of the company and they abandoned load consolidation in favour of independent branches. (A more detailed description of this case study is given in Klein and Eason, 1991).

In this example the scenarios were implemented in trial systems so that the human and organisational implications could be experienced by the stakeholders. As they worked through the business process in the two scenarios the staff became acutely aware of implications they had only dimly appreciated before the trial began and they were very clear about the route forward when the trials ended. This approach is effective but it has several drawbacks; it is expensive to mount such trials, they may be disruptive to business and it is difficult to test all the relevant scenarios. To implement a trial it is necessary to have a fully developed technical system which usually means that the trials are undertaken late in the development process and it may be difficult to make major changes in the technical system after the trial. Ideally we require a relatively cheap way of developing and evaluating socio-technical scenarios early in the development process which are sufficiently realistic to give stakeholders the opportunity to evaluate the implications of each scenario with confidence.

Scenario evaluation as a social process

In most system development processes there is now a place for would-be users to play a role. In a number of techniques a social process is created in which stakeholders can consider future opportunities. In the USA, for example, JAD (Joint Application Design, August 1991), provides users and designers with opportunities to meet together in workshops to generate and evaluate future technical systems. In the UK in the ETHICS methodology (Mumford, 1983) users take responsibility for the identification and development of future socio-technical systems. The Search Conference approach developed in Australia (Weisbord, 1990) creates a process for stakeholders to analyse future requirements, search for solutions and seek consensus and commitment to a particular route forward. In Scandinavia (Greenbaum and Kyng, 1991) participative design has been developed with a specific aim of helping shopfloor and craft based users play significant roles in the development of systems which can enhance and develop their skills rather than replace them.

Although there are variations between these approaches they share a common basic structure and have a common purpose. They are participative processes which invite all significant stakeholders in the change process to help create future scenarios. They provide opportunities for stakeholders to evaluate scenarios from their own perspectives and thereby to articulate their requirements from future systems. Underlying these approaches is a belief that, despite different sectional interests, it is possible to find ‘win/win outcomes’ (Boehm, Bose, Horowitz and Lee, 1994), i.e. scenarios which would be acceptable to all stakeholders. Whilst this may be over-ambitious it is certainly true that the evaluation of a range of scenarios can identify a solution that meets a wider range of requirements than a single solution which is only evaluated against cost and technical criteria.

It is now commonplace for users to participate in systems development processes although it is often less systematic than in the methods described above.

However, there are also regular reports of users struggling when given this opportunity to participate (for example, Hornby and Clegg, 1992) and these difficulties threaten the perceived efficacy of user-centred approaches. We need to understand the difficulties users experience in order to find ways in which they can be helped to make an effective contribution. The difficulties can be listed as:-

(i) | Understanding the technology and specifically the way it might be applied in the user’s work setting. When an application is presented in technical terms it may be difficult to relate to the work domain. It is often unclear to potential users what the benefits of the technology might be and what problems it might cause. |

(ii) | Imagining alternative forms of work made possible by the technology. Although there are many different ways of applying information technology it is not easy for people to envisage alternative ways of working that are outside of their experience. What, for example, would it really be like to be a tele-worker? |

(iii) | Determining realistic requirements for future systems. Because of their lack of knowledge, users tend to have unrealistic expectations of technology; wildly optimistic of what can be achieved or deeply pessimistic of its impact on everything important. Users need to develop realistic hopes and fears before they can make an effective contribution. |

(iv) | Agreeing system requirements with other stakeholders. Inevitably some choices are more beneficial to some stakeholders than others and some will have more overt power and influence than others. They need a way of examining the options to discover where there is the greatest possibility of consensus and support. |

Scenario evaluation as a cognitive process

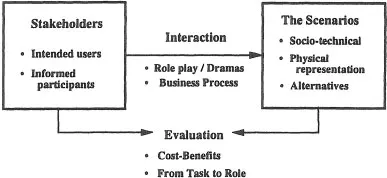

As a result of the increasing use of scenario based design a number of practices are emerging to help stakeholders play their role in this process. They constitute largely untested ways of dealing with the problems listed above. These practices, summarised in figure 2, also involve the users in specific kinds of cognitive tasks and underpinning them are a set of beliefs about how users can best tackle these tasks.

Figure 2 Towards the effective management of the evaluation of future systems

The first set of beliefs concern the nature of the scenarios that have to be created to help the stakeholders. They need to be socio-technical representations; if they are just technical representations the stakeholders have difficulty working out how they affect the work people do. The scenarios therefore have to be expressed in terms of the set of human work roles needed to accomplish the business process and the manner in which the technology will support each work role. The enterprise modelling approach included in the ORDIT methodology (Olphert and Harker, 1994; Eason, 1996; Eason, Harker and Olphert, 1996) provides a means of creating such scenarios by rel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Part One: Job Design and Analysis

- Part Two: Learning and Training

- Part Three: Medical Ergonomics

- Part Four: Applied Cognitive Psychology

- Part Five: Product Design and Evaluation