- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Driver Behaviour and Training: Volume 2

About this book

Research on driver behaviour over the past two decades has clearly demonstrated that the goals and motivations a driver brings to the driving task are important determinants for driver behaviour. The importance of this work is underlined by statistics: WHO figures show that road accidents are predicted to be the number three cause of death and injury by 2020 (currently more than 20 million deaths and injuries p.a.). The objective of this second edition, and of the conference on which it is based, is to describe and discuss recent advances in the study of driving behaviour and driver training. It bridges the gap between practitioners in road safety, and theoreticians investigating driving behaviour, from a number of different perspectives and related disciplines. A major focus is to consider how driver training needs to be adapted, to take into account driver characteristics, goals and motivations, in order to raise awareness of how these may contribute to unsafe driving behaviour, and to go on to promote the development of driver training courses that considers all the skills that are essential for road safety. As well as setting out new approaches to driver training methodology based on many years of empirical research on driver behaviour, the contributing road safety researchers and professionals consider the impact of human factors in the design of driver training as well as the traditional skills-based approach. Readership includes road safety researchers from a variety of different academic backgrounds, senior practitioners in the field of driver training from regulatory authorities and professional driver training organizations such as the police service, and private and public sector personnel who are concerned with improving road safety.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Driver Training and Education

Chapter 1

Interactive Scenario Modelling for Hazard Perception in Driver Training

Abs Dumbuya, N. Reed and G. Rhys-Tyler1

Q.J. Zhao and R.L. Wood2

Q.J. Zhao and R.L. Wood2

Introduction

The three primary elements of a vehicular traffic system are the driver, the vehicle and the road environment. Drew (1968) suggests that the driver component of this system is the most complex as the human driver is generally characterized by higher-level processes, such as perceptual capabilities (eg vision, hearing and sensation of forces on the body); cognitive functions (eg learning, motivation and attitude); and control functions (eg steering and braking). For example, learning could concern the ability of the driver to improve their understanding of the driving task through repetition, with feedback allowing error adjustment to be made to improve situational responses. Control function, on the other hand, could address the execution of actions, typically those involved with stabilizing the vehicle’s path and speed, eg steering, braking and acceleration.

Different types of driver behaviour models are critically summarized in Michon, (1985). Some of these include mechanistic models, adaptive control models (eg servo control and information flow control), motivational models and cognitive models. Michon’s categorization of driver behaviour models is illustrated in Table 1.1.

Task analysis – the seminal work by McKnight and Adams (1970a, 1970b; McKnight and Hundt, 1971) provides a comprehensive analysis of driver behaviour impacting the vehicular traffic system. They identified and categorized driving into over 1700 elementary tasks, eg accelerating, steering, speed control, lane usage, reacting to traffic, planning, car following, lane changing and so on.

Table 1.1 Categorization of Driver Behaviour Models

| Taxonomic | Functional | |

| Input-output (behavioural) | Task analysis | Mechanistic models Adaptive control models - servo-control - Information flow control |

| Internal state (psychological) | Trait models | Motivational models Cognitive models |

Source: Michon, 1985.

Trait models attempt to capture individual personality characteristics, eg aggressive or cautious driving, influence of stress etc. These traits have an influence in certain types of driving behaviour; for example, many studies have demonstrated the effect of personality traits on the likelihood of accidents (Iversen and Rundmo, 2002; Lawton, 1998 and Ulleberg, 2002).

Cognitive models seek to decompose the complexity in driving behaviour into distinct hierarchical structure. Michon is one of the proponents of using cognitive models in modelling driver behaviour, proposing a hierarchical structure of driving behaviour divided into strategic (planning), tactical (manoeuvring) and operational (control). In this structure, planning and determination of goals is achieved at the strategic level, whilst selection of these goals is performed at the tactical level. At the operational level, actions are executed to achieve the planned goals and objectives. Tactical level decisions are critical for the support of operational goals execution. To understand these decisions, motivational models seek to capture the driver’s internal or mental state in terms of cognitive functions (eg emotions, intentions, beliefs). Cognitive modelling using Michon’s hierarchical structure is widely accepted to offer a sound basis for modelling driving tasks.

Whilst mechanistic models identify driving behaviour as physical systems, for example the fluid flow analogue of traffic, adaptive control models describe driver behaviour as either continuous or intermittent tasks, ie servo-control models or flow charts/decision trees (information flow control models). The use of servo-control models in describing driving is particularly useful in modelling the operational mechanisms of driver/vehicle interaction. The driver usually receives input signals from the vehicle and the external environment and then steers the vehicle in response to these signals. Although advances in computer simulation have brought about increasing application of adaptive control models, such models still lack intelligence and learning capabilities because of their data driven approach.

Driving Interaction and Traffic Flow Methods

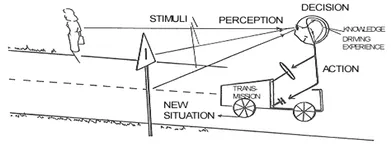

Driver behaviour modelling is an important aspect of understanding the driver within the traffic system as well as analysing traffic flow. The interactions between the key components of vehicular traffic with respect to time and space can be viewed as a typical human-machine system, ie driver (human), car (machine) and environment. Figure 1.1 illustrates some of the processes involved in driving.

Figure 1.1 Basic Components of Driving (cited in Pursula 1999)

The driver receives information from the environment (perception), makes a decision based on the traffic information and then executes actions to respond accordingly. These interactive tasks are summarized in (Allen et al, 1996 p 27-28), and include:

Control concerns psychomotor functions that stabilise vehicle path and speed against various aerodynamic and road disturbances. Guidance involves perceptual and psychomotor functions coordinated to follow delineated pathways, adhere to implied speed profiles, interact with traffic and avoid hazards. Navigation involves higher level cognitive functions applied to path and route selection and decisions regarding higher-level traffic interactions (eg avoiding congestion).

In fact, these tasks can be further simplified into three driving actions: perception-decision-control. This is often referred to as open and closed loop interaction. The open-loop operation is represented as a perception-decision-action sequence, whilst closed-loop operation involves update to the driver/vehicle current state based on feedback from the environment.

Within the context of traffic flow, driver interactions can be explored in terms of vehicle following and lane changing using different approaches (ie micro-, meso- or macroscopic levels of behaviour details). Vehicle following is a fundamental driving task and plays a very important role in understanding traffic flow (Rothery, 1997). Vehicle following is usually triggered when a driver cannot maintain their preferred speed and must adjust their speed to match the speed of the lead vehicle, whilst keeping a safe distance, referred to as either time- or distance headway. For a thorough review of this subject see Brackstone and McDonald (2000). On the other hand, lane-changing behaviour is a more complex task than vehicle following, since consideration must be given to driving conditions in the target lane and the intentions (perceived behaviour) of other drivers in the target lane. An important part of lane-changing behaviour is gap acceptance involving the assessment of the critical gap length of the target lane.

The level of detail required in a model is dependent on the intended application. Several methodologies can be adopted in representing the driving components, ie vehicle, road network and driver. Macroscopic models ‘describe the entities and their activities at a low level of detail’ (Lieberman and Rathi, 1997 p 6) requiring less computational time. At the same time, these models are low fidelity and often based on the deterministic relationships between the traffic entities. Microscopic models on the other hand offer the most general method for realistically describing and analysing the nature of vehicular traffic. They are high fidelity models capable of representing the individual characteristics of the traffic elements such as driver, vehicle and road network in significant detail. Representation of such characteristics within microscopic simulations produces realistic interactions. In contrast, meso-scopic models are mixed fidelity - these models describe some elements of the traffic system at a higher level of detail but represent the interactions at a relatively lower level of detail than microscopic traffic simulation models.

Various other methods have been proposed in modelling driving interactions and traffic flow. These include rule-based systems, fuzzy logic, probabilistic models, hidden markov driver models and finite state machines. However, in his review, Michon noted in 1985 the lack of research in driver behaviour modelling. He observes that such lack of research in this area can be attributed to a number of issues, including failure to improve on the driver behaviour models of the sixties (eg car following) and a lack of interesting research ideas on driver behaviour. Concerning the future direction of driver behaviour modelling, he suggests that ‘we are heading for an intelligent, knowledge and rule based model of the driver that will be capable of dealing with a wide variety of realistic, complex situations…’. Addressing these issues in the development of visual databases and scenarios for driving simulators would greatly improve behavioural responses of simulator participants.

Visual Database and Scenarios for Driving Simulators

Driving simulators are used extensively to train drivers to develop new or improved skills. Examples of these include; TRL TruckSim and CarSim (TRL, UK); Iowa Driving Simulator (University of Iowa, USA); Leeds Driving Simulator (University of Leeds, UK); COV Driving Simulator (University of Groningen, Netherlands); SIRCA simulator (University of Valencia, Spain); and INRETS Sim2 /ARCHISIM (INRETS, France). A widely successful driver-training simulator is that used by BSM, developed by FAROS (Wicky et al, 2001). Driving simulators provide safe, controlled and cost-effective environments in which it is possible to analyse traffic flow, highway design and driver psychology using objective performance measures. In general, these simulators consist of a fixed or motion cabin, visual projection and sound systems and a traffic generation module. The traffic generation module typically consists of visual database and driving scenarios.

It is important to make a subtle distinction between visual database and driving scenarios used in driving simulators. Visual databases are typically three-dimensional computer generated worlds developed using computer graphics tools such as Multi-Gen, 3D Studio Max or Open Inventor, although recently photorealistic imagery has been used to produce complex photorealistic scenery. The scenery can contain static and non-static objects, for example buildings, sky, humans and vehicles. On the other hand, driving scenarios are those elements of the traffic generation module that support the specification and control of parameters for vehicle, driver, road network and task definition for any specific study. There is a growing debate on the realism of visual databases and scenarios. Parkes (2005) provides a very interesting discussion on improved realism and improved utility of driving simulators for the purpose of training. He contends that high fidelity of the simulator or realism in the visual database and scenario may not be necessary for the purpose of training. He underpins his argument with the concept of essential realism – developing reality essential for a particular training requirement rather than improved face validity. However, it can equally be argued that improved realism in visual database and driving scenarios is desirable for specific applications, for example perceptual or cognitive behaviour. Allen et al (2003 and 2004) argue that given a particular application (eg in research, driver training and assessment), scenarios and visual databases ‘need to be designed and chosen to match real-world conditions as much as possible to ensure proper transfer of training’.

Scenario specification or authoring can be achieved at three levels (Papelis, 1996). Examples of these levels include hand-tuned scenario authoring where direct access and modification o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Part 1 Driver Training and Education

- Part 2 Simulation and In-Vehicle Technology

- Part 3 Young Driver Behaviour and Road Safety

- Part 4 Vulnerable Road Users

- Part 5 Personality, Emotions and Driving

- Part 6 At-Work Road Safety

- Part 7 Crash Analysis

- Part 8 Driver Attention and Knowledge

- Conclusion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Driver Behaviour and Training: Volume 2 by Dr. Lisa Dorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.