CHAPTER ONE

An Anglo-Irish Childhood

A town mouse I was born and bred, and the town which sheltered me was one likely to leave its mark upon its youngest citizens, and to lay up for them vivid and stirring memories. Dublin, as I woke to it, was a city of glaring contrasts. Grandeur and squalor lived next door to each other, squalor sometimes under the roof of grandeur.1

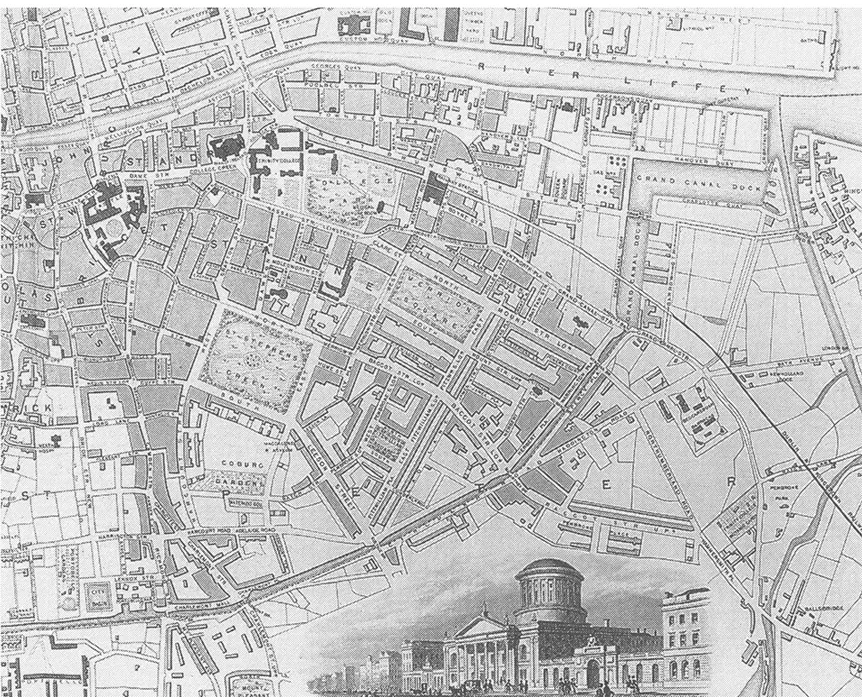

Figure 1.1 Inner south-east Dublin in 1850, from The Illustrated Atlas and Modern History of the World, ed. Montgomery Martin (London, ? 1849-51). By permission of Birmingham Central Library

One of the most striking architectural features of the Dublin in which Stanford grew up was the network of residential streets (now mainly converted into offices) which lay south of the Liffey and centred on St Stephen’s Green (see Fig. 1.1). Generally a product of eighteenth-century prosperity, showing some elements of enlightened town-planning not normally associated with Great Britain, the rows of Georgian terraces and squares, with their deliberate symmetry and uniformity, are now one of the most imposing remnants of the Anglo-Irish ruling class which dominated Ireland from the eighteenth century to the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922. Many street names reflect their Georgian heyday, referring to famous politicians and other luminaries of the time - Grattan, Fitzwilliam, Harcourt and Herbert - and it was here that much of Ireland’s political, social, cultural and bureaucratic elite made its home, from the days of the area’s first being built until the community’s decline and virtual disappearance in the inter-war years.

The foundations of this ruling class are to be found in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when successive monarchs, most notably Elizabeth I and James I, and the republican Cromwell, encouraged members of the English gentry and middle class to emigrate to Ireland and to ‘civilise’ and subordinate the indigenous population. As in so many aspects of British history, it was the outcome of Henry VIII’s break with Rome that led to this change in policy towards Ireland, which had, by and large, been ignored by earlier monarchs except when insurrection was at its most blatant. The Catholic clergy of Ireland were far more resistant to the Reformation than their English counterparts and Henry acted decisively against them and others. Land seized from the monasteries was redistributed to a new wave of English immigrants and the Dublin parliament passed a law explicitly recognising Henry’s supremacy as monarch. The policy was sustained over decades; after monastic lands ran out property was seized from the indigenous population.

The policies of Henry, Elizabeth and James were relatively benign compared with what followed. Believing that Charles I had some pro-Catholic sympathies, much of Ireland supported the Royalist cause in the Civil War. After Cromwell’s victory in 1649 the Irish were subjugated with little or no mercy. Land redistribution to English incomers took place on a vastly greater scale than hitherto and there was an attempt at ‘ethnic cleansing’ through a combination of slaughter of Catholics and the passing of a law (the Act of Settlement, 1652) which forced rebellious Catholic landowners to move west of the Shannon.2 James was defeated in the Williamite Wars (1689-91), and the Protestant hegemony cemented.

The upshot of this last and most dangerous act of Catholic rebellion was the determination of successive English monarchs and governments to maintain Protestant supremacy. This was mostly achieved by a succession of Acts passed over the four decades from 1690 collectively known as the Penal Code (contemporaneously known as the ‘Popery Laws’). This legislation forbade, amongst other things, the entry of any Catholic into the army or navy, the holding of posts in central or local government, entry into the legal profession, and the education of a child in the Catholic faith; it also removed the right of Catholics to vote. Catholic land could be passed from generation to generation but only on the old Merovingian principle of equal division of property between all sons -a simple method of ensuring that Catholic landholdings, already negligible as a part of the whole, became progressively more fragmented. The Penal Code cemented the Protestant domination of Ireland by emasculating the power of the remaining Catholic gentry.3

This social construction of Protestant, or rather more specifically Anglican, supremacy leads us directly to the physical construction of Dublin’s Georgian terraces, a tangible manifestation of the domination and prosperity of the Anglo-Irish ruling class in the eighteenth century. Ireland was prosperous and Dublin was its thriving cultural, social and commercial centre. Their position secured by prosperity combined with legalised discrimination, the Anglo-Irish easily became a ruling elite, confident and optimistic. Such was this degree of prosperity and self-sufficiency that during the course of the century the Anglo-Irish began to identify themselves less with England and more with Ireland. English rule seemed to them to comprise much taking but little giving. An economically strong but politically compliant Ireland was also in English interests and, in order to assuage the growing Anglo-Irish spirit of independence, the British government consented to the modification of the powers of the Irish Parliament in 1782. Its leader, Henry Grattan, supported the repeal of aspects of the Penal Code, but made little progress since many more of the Anglo-Irish were sceptical about the need for such action and there was little material change between pre-and post-1782 parliaments.4 Grattan’s lack of success was unfortunate, to say the least: growing frustration amongst Catholics and some Protestants, most notably Wolf Tone, allowed the success of the French Revolution to fire their imagination and culminated in the Irish Rebellion of 1798. This revolt was swiftly and brutally put down by the British Army but had so winded the Anglo-Irish that they voted their own Parliament out of existence and accepted the Act of Union - a concept to which most of them had previously been thoroughly hostile - with barely a murmur.

The Act of Union sounded the muted death knell of the Anglo-Irish. During the nineteenth century Dublin declined gradually as England became the overwhelmingly dominant partner in the relationship. The industrialisation of England was not matched in Ireland, not least because of its relative paucity of natural resources, and this dearth of heavy industry contributed greatly to the shift in England’s favour. These unfavourable circumstances were amplified by poor agricultural conditions and unsympathetic rule from London, which preferred coercion to encouragement. Even the most tentative shoots of the welfare state which emerged in Great Britain in the nineteenth century were unknown in Ireland, while the circumstances in which the poor and needy lived were much worse than those on the mainland. Inhumane government was exacerbated by natural disasters, the worst of which was, of course, the potato famine of the late 1840s. Perhaps one million people died and the crisis triggered a wave of emigration, mainly to the United States, sustained for the rest of the century. The population declined rapidly and never recovered: in 2000 it was still barely two-thirds that of 150 years earlier.

In the midst of these crises the Anglo-Irish found themselves in an uncomfortable midway position, neither fully endorsing the actions of the British government nor supporting the demands of the Catholic majority. Had it not been for its own cohesiveness the community might well have disintegrated into two rival camps - one pro-Nationalist and one pro-Union - reflecting the potential schizophrenia inherent in its constitution and history. Of decreasing use to the British government, effectively undermined by Catholic Emancipation and other subsequent measures,5 and regarded with increasing suspicion by the Catholic Irish, the Anglo-Irish found themselves steadily marginalised during the nineteenth century. They were, in effect, the forerunners of the last gasp of the British Raj of the twentieth century, upholding their social exclusivity, their dominance of the professions and civil service, and refuting their geographical isolation and declining status by a hectic social calendar of soirées, dances, concerts, nights at the theatre and days at the races.

The point from which the Anglo-Irish themselves perceived this decline is not clear. Joseph O’Brien asserts that

Gradually the wealthiest segment of the population withdrew from Dublin, and the noble residences adorning the best streets and fashionable squares exchanged their occupants [the aristocracy] for the new pace-setters of society - the professional classes, especially the barristers and attorneys, who thrived on an admixture of law and politics in a city that retained in Dublin Castle a top-heavy bureaucracy.6

For those born in the centre of this professional, and especially legal, milieu, however, Dublin’s status may well have grown during the nineteenth century: Harry Plunket Greene wrote that, ‘Ireland in those days . . . was a country of intensive brilliance, more of imagination even than culture.’7 Certainly Georgian-style terraces were still being built in Dublin’s exclusive Merrion Square area in the 1830s, suggesting that at this point, little or no decline was evident. Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, so close to the social upheavals leading to partition and independence, the city was still viewed by those looking back from the wholly different world of the inter-war years as a major social centre: ‘Dublin at this time, about 1900, was amazingly gay and the season was a brilliant one. People used still to come up and take houses for the season, and wealthy and poor and good family mingled for a few weeks at dinners, dances, Court functions, and all sorts of miscellaneous sports and games.’8 In truth, for the professions at least, post-Union Ireland was a rich and generally pleasant place with sour notes only creeping in towards the end of the century, when the number of people questioning their status and exclusivity exceeded the small group any elite can reasonably expect to have to deal with and to shrug off.

The nineteenth-century professional cadre comprised Dublin’s most successful lawyers, merchants, clerics, doctors and civil servants. As in the eighteenth century their sense of cohesiveness was greatly reinforced by their being almost exclusively Anglican (this dominance declined steadily during the nineteenth century but Anglicans remained over-represented in proportion to their population in most professions). The group was also content to stay in Ireland: summer was often spent on a rural estate or at a resort and the winter in Dublin. Visits to England were generally unnecessary, as well as being long and, especially in the earlier part of the century, sometimes dangerous (steamships commenced regular journeys across the Irish Sea shortly after the end of Napoleonic Wars, but the railway did not reach Holyhead until the late 1840s, meaning that any journey further than the British western coastal areas remained a gruelling expedition until well into the 1850s). Intermarriage reinforced insularity. As Harry Greene put it: ‘The “home” spirit so pervaded the families that each fresh generation settled down comfortably to carry on the family tradition in the familiar sphere. With the exception of a few restless spirits its youth went into the Church or the Law or Medicine or took root in the land at home.’9

As Joseph O’Brien has noted, it was the legal profession which led the Anglo-Irish elite. Law could lead to the very pinnacle of the social ladder and was a safe and eminently respectable occupation. This supremacy was recognised by all, as was the role the law played in Dublin social life:

It is quite certain that the legal element dominates society in Dublin and is held in the highest respect. The leading members, i.e. the Chancellor and the Judges, do duty for the absentee nobility who have long since ceased to reside in the little capital, only putting in an appearance during the Castle season. Hence the lawyers and their wives do the ‘representation’, live in the finest houses, drive the finest carriages, and entertain the Lord Lieutenant.10

Even in ...