- 390 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During the second half of the twentieth century, an economic boom, driven by advances in technology, has led South Korea to become the world's fastest growing economy. But, there were also social factors associated with this shift. In this book, Daniel J. Schwekendiek examines South Korea's socioeconomic evolution since the 1940s.After a brief introduction to Korean history from the late Joseon Dynasty to the division of the Korean peninsula into two occupied zones in 1945, the focus of the book shifts to the rapid socioeconomic development and change that took place in South Korea in the twentieth century. Topics covered include demography, rural-urban development, economic planning, and international trade, in addition to lower and higher education. Important, but understudied areas, such as social capital, nutritional improvements, the rise of capitalist consumerism, and recent nation branding issues, are also addressed.Rarely has a resource incorporated such unique macro-historical perspectives of South Korea, especially in the context of social development. Throughout the book, the author corroborates historical events with empirical data. With over one hundred figures and illustrations, suggested readings at the end of each chapter, and comparisons with North Korea, South Korea will be a crucial reference work for scholars and advanced students in Korean and East Asian Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access South Korea by Daniel J. Schwekendiek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Historical Development of Korea

1.1 Korea in Macrohistorical Perspective

In order to review the long-term development that Korea experienced, let us first consider gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, which is by far the most common indicator of living standards in historical research. GDP commonly reflects the total value of all goods and services produced in a specific country within a year. GDP divided by a country’s population is commonly accepted as a broad indicator of how well the average person of that country fares.

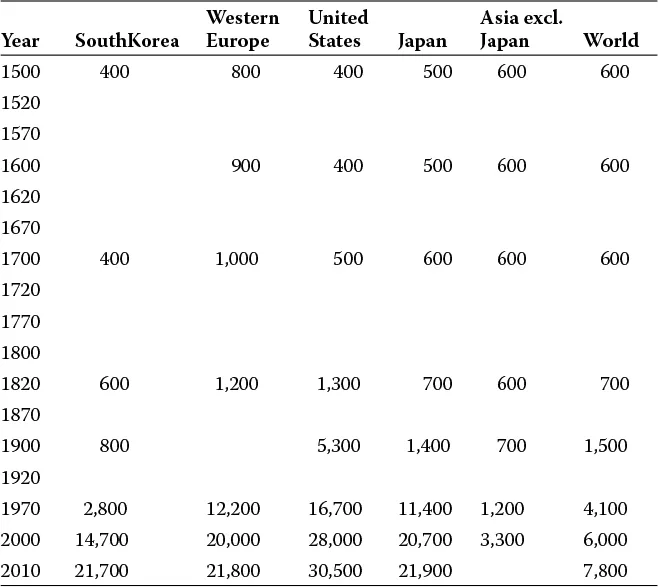

Table 1.1.1 shows the annual GDP per capita in international dollars of South Korea, select (early industrializing) nations, such as the United States and Japan, Western Europe as a whole, all of Asia with the exclusion of Japan, and the world’s average GDP per capita from 1500 to 2010, drawing from Angus Maddison’s groundbreaking works (Bolt and van Zanden 2013; Maddison 1995, 2001, 2003). During the 1500s, living standards in Korea were almost equivalent to Japan and the United States, yet living standards in Western Europe—here represented by twelve nations, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom—were twice as high at that time. Even on a global scale or the rest of Asia (both six hundred international dollars), Korean living standards were considerably lower (four hundred international dollars in the 1500s). By 1700, the gap between Korea (four hundred international dollars) and Western Europe (one thousand international dollars) widened compared with the 1500s. By 1820, the next point of reference, the United States—the most important colonial offshoot of Britain and continental Western Europe that pioneered the industrial revolution—pulled ahead while world GDP per capita hovered at 700 international dollars, and Korea’s slightly below that value (600 international dollars). By the 1900s, the century of industrialization in the West that triggered the era of high imperialism, Korea (800 international dollars) fell dramatically behind the world average (1,500 international dollars). In a similar vein, the disparity between Korea and the most developed nation at that time, the United States (5,300 international dollars), widened dramatically further, with Americans enjoying six to seven times better living standards than Koreans. As Japan began to industrialize and catch up to the developed West, its GDP per capita doubled from 700 international dollars in 1820 to 1,400 international dollars in 1900. By the year 1970, the time when Korea initiated heavy industrialization, living standards in Korea (2,800 international dollars) were still remarkably below the world average (4,100 international dollars). Korea’s gap widened even further when compared with the most advanced nations at that time, including the United States (16,700 international dollars and thus almost six timers higher), Western Europe, and Japan (12,200 international dollars and 11,400 international dollars and thus about four times higher, respectively). Though the gaps were still large compared with the most developed nations, Korea surpassed Asia’s average (1,200 international dollars) for the first time in history by 1970, due to rigorous economic planning (chapter 3.1). Consequently, South Korea’s GDP per capita surpassed the world average by the year 2000. Also the gaps compared with the most developed nations in the West as well as Japan began to close by the year 2000. Last but not least, by the year 2010, postindustrialized South Korea’s GDP per capita (21,700 international dollars) was on par with Japan (21,900 international dollars) and Western Europe (21,800 international dollars).

The rise of South Korea’s economy in just a few decades has sometimes been described as “the miracle on the Han River” (Jun, 2011)—the Han being the main river running through the capital, Seoul. Within a few decades after World War II, South Korea became one of the world’s most developed nation—which, from a macrohistorical point of view, is remarkable as Korea was clearly below the world average and behind Asia’s average for many centuries during premodern times. The underlying economic and social factors for this rapid and enormous growth miracle will be explained in a latter section of this work. What is most important to learn from this exercise (table 1.1.1) is that Korea was extremely poor before modern times. The country never had any overseas colonies, which was unlike many other seafaring nations that were residing on islands or peninsulas (Schwekendiek 2012:4–5).

Table 1.1.1 GDP per capita in the world, 1500–2010.

Note: Rounded values shown. Data for the year 1900 pertain to 1913; data for 1970 pertain to 1973. Data for 2000 pertain to 2001. Western Europe is represented by twelve nations: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Source: Maddison (2003:184, 262), Maddison (1995:238), Bolt and van Zanden (2013).

In five thousand years of Korean history, Korea has never invaded another country (Park 1970:280). In the past, given the country’s economic underperformance, Korean culture has never made it into the Western hemisphere, let alone barely outside of the Korean peninsula. The twenty-first century has been the first time in history that Korean influence has reached out to the rest of the world on a massive scale—be it through technological products, such as Korean flat-screen TVs in almost every living room, or cultural products, such as Korean pop (K-pop) culture. This spread of K-pop includes the most recent success of the Korean rapper PSY, whose hit, “Gangnam Style,” became the first video to reach one billion views on YouTube in the history of the website.

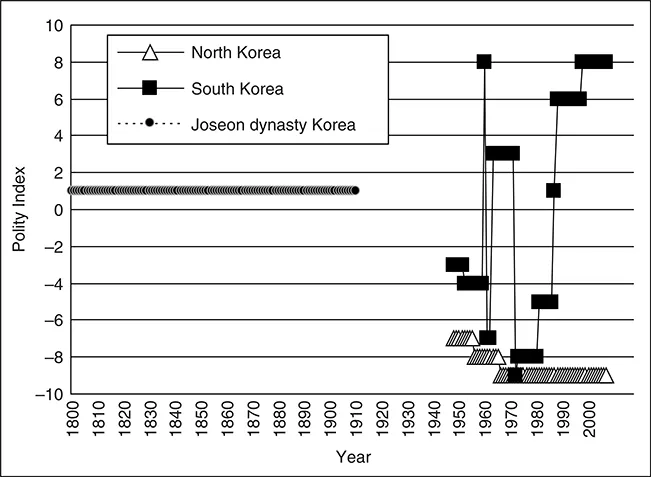

Since this research primarily focuses on the economic and social development of South Korea, a short discussion of Korea’s overall political development is in order. The Polity IV index is a widely applied indicator of political freedom that measures key qualities of a democratic system. The index ranges from +10 to −10, with the former indicating full democracy and the latter representing full autocracy for a specific country. This composite index is based on the following subindicators: “executive recruitment” (which incorporates questions such as, how are political leaders selected?), “constraints on executive authority” (an indicator that addresses if there are in fact veto players or accountability groups in the country), and “political competition” (e.g., if political participation is free of government control). Figure 1.1.1 depicts Korea’s political development from the eighteenth to the twenty-first century using the Polity IV index, with a special focus on the separate development in South Korea and North Korea after the division of the Korean peninsula at the end of World War II. Data for the colonial period (1910–1945) are lacking as Korea lost political sovereignty to Japan (chapter 1.2). Data from 1800 to 1910 refer to Joseon dynasty Korea (1392–1910).

Figure 1.1.1 Political development of the Korean peninsula, eighteenth to twenty-first century.

Source: Polity IV. Dataset in author’s files. See also Appendix 5.1.

Figure 1.1.1 illustrates that Joseon dynasty Korea—like most other monarchies—was never completely democratic in premodern times (1800–1910). On the other hand, there were serious checks and balances for the king during the Joseon dynasty that reduced his power (Palais 1975). This lack of authority explains the rather neutral Polity IV score in premodern times. After liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, the two Koreas split and held separate elections in 1948. Neither of the Koreas were initially rated as democratic, although North Korea (scoring between −7 and −8) was substantially more autocratic than South Korea (scoring −3 to −4) from the 1940s and throughout the 1950s. In the subsequent decade, after the Korean War (1950–1953), South Korea became slightly more democratic (scoring mostly +3), while the contrary was true for North Korea (dropping to −9 since 1966 without improvements ever since). The 1970s was the time when South Korea pushed its heavy industry at all costs under military rule, and political democracy declined massively to a value of −8 and −9, thus being almost as totalitarian as its communist neighbor in the North. By the mid−1980s and early 1990s, redemocratization gradually occurred in the South. Since the late 1990s, South Korea’s political performance improved to a score of +8. In other words, political conditions have dramatically improved in South Korea ever since the 1980s. All current generations in South Korea have been raised under democratic rule, which in turn enables them to enjoy a liberal lifestyle, freely choose the goods they wish to buy, and articulate their interests in the public without repression. For illustration, in the 1970s, when South Korea was almost as autocratic as North Korea, even calling the president by name in public or in private conversation was deemed as dangerous, for people feared getting arrested for that act. Conversely, in this day and age, Korean comedy shows, such as the Korean version of Saturday Night Life (SNL), frequently make fun of or even ridicule the Korean president on television. Mocking the president was unthinkable only a few decades earlier and would have resulted in imprisonment or other forms of punishment.

What is perhaps most important to note is that South Korea’s change to democracy was achieved from within and not from outside. The masses and intellectuals were the ones who gradually shifted South Korea to a democracy. Ever since the foundation of South Korea, the Korean military, politicians, and industrialists were forming a triple alliance to rule and develop the newly formed nation in the course of the Cold War (Lie 1998). Arguably, none of them had a primary interest in improving social living conditions; hence political autocracy ensured their power and profit. The masses, whose living standards did not improve at the same pace as the economy, were the ones suffering from political oppression and started demonstrating for reforms. For illustration, President RHEE Syngman’s autocratic rule (who was in office from 1948 to 1960) was ended by massive student and labor demonstrations in 1960 (also known as the April Revolution) that preliminarily led to democracy (scoring an +8 in the Polity Index in 1960). A military strongman, PARK Chung Hee, seized power in 1961 through a coup and ruled the nation until 1979 when he was assassinated by the chief of his own security service. Among other factors, his assassination was perhaps a result of massive student and labor protests against his autocratic rule in that year—although this awaits further analysis (Nahm 1993:300). President CHUN Doo Hwan’s autocratic rule started in 1979 and was opposed by student protests that culminated in the Gwangju Uprising in 1980. This uprising led to Chun’s drastic decline in popularity. When CHUN Doo Hwan declared another military strongman, ROH Tae Woo, as the presidential candidate in 1987 (as the constitution limited CHUN Doo Hwan’s reelection), nationwide protests, known as the June Democracy Uprising, led to political reforms calling for free elections and better civil rights. As a result, ever since 1988, South Korea scored +6 or above in the Polity Index.

As mentioned above, what is most striking about South Korea’s democratization was that it was brought about from within—not by external powers nor by the ruling elites in South Korea. Korea’s way toward democratization was long and bloody, but most importantly, it was achieved by the people—since they were the ones who really paid the price for the nation’s economic modernization. South Korea’s determined way to be a true “re-public” is admirable considering that Korea has never experienced democracy in premodern times nor that South Korea has been democratic for long periods before 1988 (Figure 1.1.1). Whether or not South Korea’s way to democratization can serve as a role model for other nations is beyond the scope of this book.

Suggested Readings

Maddison A. 1995. Monitoring the world economy, 1820–1992. Paris: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Maddison A. 2001. The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective. Washington, DC: OECD.

Palais J.B.. 1991. Politics and policy in traditional Korea. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press

1.2 Korea in the Era of High Imperialism

The industrialization, pioneered in the West, was a game changer. Scholars have still not yet reached a consensus on whether the West was economically ahead of the East in premodern times or the situation was vice versa. This ongoing debate is commonly referred to as the “Great Divergence” in literature, where West-East comparisons are often based on European and Asian nations, such as Britain and China. However, one might generally agree that the differences between the East and the West were not that extreme in premodern times, regardless of whether it was the West or East that was somewhat ahead. Table 1.1.1 had already demonstrated that the European nations and their colonial offshoots (particularly the United States) began to rise from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. The enormous economic rise of the West, thanks to industrialization, in turn led to new innovations that have made these nations even richer (Allen 2011).

The industrialization, a period in which societies began to transform from agricultural production to industrial manufacturing, triggered an era of high imperialism in the nineteenth century (which culminated in two world wars by the early to mid-twentieth century). The decline in transportation costs through the innovation of steamships and expansion of railway networks meant that troops and supplies could be delivered to any corner of the world and in a much shorter span of time. The industrialization also changed military warfare, leading to the devastation of the antiquated Spanish fleet and the rise of the British empire. Technological spin-offs of the industrial revolution, such as gunboats or the fully automated machine gun invented in the nineteenth century, triggered European encroachments into Asia, Africa, and elsewhere. To further illustrate the dramatic technological rise of Europe, in the country that is known as today’s Zimbabwe, over three thousand Africans were literally mowed down by fifty British soldiers with an automated machine gun in 1893, firing at a rate of six hundred shots per minute (Von Luepke 2013). About 85 percent of earth’s land was occupied or claimed by one imperial power or another in the era of high imperialism (Larsen 2008:2). Some seven industrialized (or industrializing) nations saw their territories increasing dramatically from 1876 to 1915, including Britain (4 million square miles), France (3.5 million square miles), Germany (over 1 million square miles), Belgium and Italy (over 1 million square miles), as well as the United States and Japan with 100,000 square miles (Caprio 2009:19). Not surprisingly, Korea, which eventually was taken by Japan, also became a colonized nation. The Korean peninsula is therefore no exception to the rule—annexation was almost inevitable in the era of high imperialism. In other words, if Japan had not colonized Korea, it would have been very likely that another imperial industrialized nation may have done it.

In order to understand Korea’s colonization during the era of high imperialism, one must take into consideration that it takes two parties for this to happen: the colonizer and the colonized nation. Industrialized nations became active colonizers throughout the course of the nineteenth century. The question remains: why did Korea not “discover” the industrialization? Economic historian Robert Allen (2011) goes too far in saying that any nation with an advanced agricultural economy was a likely candidate to pioneer the industrial revolution (it was eventually due to the local coal industry that the British discovered it). Why did Korea not catch up to the West and start to actively take control of the surrounding foreign territory the way Japan did? The aforementioned description of an advanced agricultural economy would certainly fit premodern Korea. For example, Korean farmers were so famous that they pioneered rice farming in Central Asia and some parts in the United States. The world’s oldest rain gauge, dating back to 1442, was invented in Korea for the purpose of rice cultivation (Song 1990:31). However, there were many factors as to why Korea never rose economically nor upgraded its military substantially, some of which will be discussed below.

Many Korean historians believe that the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) peaked under King Sejong the Great, who ruled in the early fifteenth century (Nahm 1993; Song 1990). King Sejong the Great reformed many areas, such as the military, science, economy, agriculture, and society. He also created the Korean alphabet, hangeul. Even contemporary Korean intellectuals see the first two centuries of the Joseon dynasty as the nation’s prime, and this is reflected in the banknotes currently issued in South Korea. From 2006 to 2009, the government replaced all old banknotes (Linzmayer 2012:39–40). Presently, the following people grace the face of banknotes issued in South Korea: philosopher YI Hwang (1501–1570), also known as Toegye, on the 1,000 won banknote; scholar YI I (1536–1584), also known as Yulgok, on the 5,000 won banknote; King Sejong the Great (1397–1450) on the 10,000 won banknote (which is along with the 1,000 won banknote, the most frequently used one in South Korea); and recently Lady SIN Saimdang (1504–1551) on the newly introduced 50,000 won banknote (Linzmayer 2012:39–40). Strikingly, no one from the mid-Joseon dynasty (sixteenth to seventeenth century) or the late Joseon dynasty period (seventeenth to twentieth century) is presently commemorated on banknotes in South Korea, let alone anyone from the (controversial) modern period, which was, for many decades, dominated by military strongmen and auto...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Images

- Abbreviations

- Map

- Chronology

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1. Historical Development of Korea

- Part 2. Social Perspectives of South Korea

- Part 3. Economic Perspectives of South Korea

- Part 4. Concluding Remarks

- Part 5. Appendices

- References

- Index