eBook - ePub

The Sonnet

About this book

First published in 1972, this book examines the sonnet, one of the most complex yet accessible of verse forms. It traces its history, concentrating primarily on its technical development, and fully explains the differences between the Italian and English sonnet. The study looks at several different kinds of sonnet, including condensed and expanded sonnets, inverted and tailed sonnets and irregularities of metre and rhyme, and concludes with a survey of the sonnet sequence.

This book will be useful to students of prosody and English poetry as well as those concerned with the practice of verse.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Italian Sonnet

The sonnet has a good claim to be one of the oldest and most useful verse forms in English. Like the engraving or the string quartet it provides simple yet flexible means to a classic artistic end: the expression of as much gravity, substance and lyrical beauty as a deceptively modest form can bear. The form is a minor one, but capable of the greatest things and, like all such forms which potential variety keeps alive, must jealously preserve its true lineaments and their rules.

Thus it is the Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet which is the legitimate form, for it alone recognizes that peculiar imbalance of parts which is its salient characteristic. The English sonnet, which will be discussed in the next chapter, does something rather different with the form which is not quite as interesting or as subtle. Certain other freak varieties, discussed in the third chapter, pay tribute only to the powerful echoes of the form that perversions of it essentially deny. Indeed, at all periods, fascination with the idea of the sonnet has tended to take precedence over its legitimate use. There are a multitude of experiments adapting its rhyme-schemes to the poet’s particular talents, and its history is littered with strokes of brilliant licence and the drudgery of persistent misunderstanding.

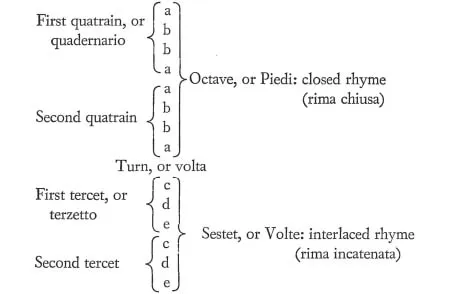

The first sonnets were written by Giacomo da Lentino, a Sicilian lawyer at the court of Frederick II, in about 1230 or 1240, and the Italian form used in the following century by Cavalcanti, Dante and Petrarch was very soon established. The practice of these early sonneteers provides us with the sonnet’s form and its terminology. The rhyme-scheme and arrangement of lines is as follows:

The essence of the sonnet’s form is the unequal relationship between octave and sestet. This relationship is of far greater significance than the fact that there are fourteen lines in the sonnet, for not every quatorzain is a sonnet, whereas the structural imbalance of parts preserved in, say, Hopkins’s curtal sonnet (see p. 29) at least acknowledges the characteristic argument or feeling of the form. This bipartite structure is one of observation and conclusion, or statement and counter-statement. The turn after the octave, sometimes signalled by a white line in the text, is a shift of thought or feeling which develops the subject of the sonnet by surprise or conviction to its conclusion.

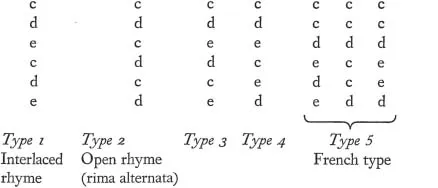

Italian theoreticians have been keen to stress the logical basis of the form, that the first quatrain states a proposition and the second proves it, that the first tercet confirms it and the second draws the conclusion. The sonnet’s form has even been linked to the syllogism (Ceva, Scelta di Sonetti, Turin, 1735, p. 42), but this is no more convincing than other theories of its origin, such as in the Greek choral ode (strophe, antistrophe, epode, antepode), in ‘the antithetic Parallelisms of Scriptural Poetry’ (Lofft, p. xxxiii) or in the musical gamut (Lofft, pp. v ff.). In fact, the sonnet’s origins support the idea that the bipartite form is the result of a prosodic sleight-of-hand. The eight lines of closed rhyme produce a certain kind of musical pace which demands repetition. Any expectation of stanzaic continuation is, however, violated by the six lines of interlaced rhyme which follow: the sestet is more tightly organized, and briefer, than the octave and so urges the sonnet to a decisive conclusion. The point is sharply put by Christopher Pilling in the sestet of a sonnet itself: ‘this sonnet’s nucleus/Leaps from octet to sestet and does not know/There are less lines to go than have been unreeled’ (Snakes and Girls, Leeds, 1970, p. 42). This tension, implicit in the sestet by virtue of its being shorter, is preserved in a number of legitimate varieties of sestet, that is to say those which acknowledge the unity of the rhyme scheme, support the organization in tercets and do not too closely resemble the octave in structure. Some of these are as follows:

It will be evident that the possible varieties of sestet are very great (Equicola, and most Italian prosodists indeed, say that any order may be followed in the sestet), but these are among the most popular: of Petrarch’s 317, for instance, 116 are of type 1,107 are of type 2 and 67 type 3; of Camões’s 196, 102 are type 1 and 56 type 2. Types such as cdcdee move even further than the French type 5 from the two tercets necessary to the Italian sonnet: by employing a terminal rather than internal couplet, it is very close to the English sonnet. Some freak forms (e.g. cccddd), while preserving some of the principles of the Italian sestet, manage invariably to violate others. The classic types are 1 and 2, and it is worth noting that of the first known group of nineteen sonnets (fifteen by Lentino, and four by contemporaries) thirteen have type 1 sestets, and six type 2. The fifth type is sometimes known as the sonnet Marotique from the practice of the early French sonneteer Clement Marot. Here the important factor is the early position of the couplet.

However, to return to the sonnet as a whole, we find that the octaves of these original specimens are not in closed rhyme at all but in open rhyme (abababab). The closed rhyme of the established sonnet was introduced by the Tuscan poet Guitone d’Arezzo (1230–94). It will be objected therefore that those sonnets with type 2 sestets do not possess the necessary contrast of rhyme– scheme, but are entirely in open rhyme, suggesting division not into quatrains but into distichs. This may be partly true but, as Wilkins points out, there is in fact a tendency to division into quatrains in the octave (as there is also in the heroic octaves of Tasso and Ariosto), and the sense and punctuation in the type 2 sestet, which Wilkins considers the later, shows a tendency towards division into tercets. Clearly the type 1 sestet is the more satisfactory, however.

The open form of octave shows the likely origin of the sonnet in the strambotto in its normal Sicilian form – the eight-line canzuna sung by Sicilian peasants but not actually recorded until later than the time of Frederick II. Type 2 sestets hint a similar origin from the strambotto, but Wilkins believes that type 1 is earlier, and anyway the six-line canzuna is very rare. Wilkins follows Rajna in thinking the sestet simply a stroke of inspiration, and some critics (e.g. Praz) believe that this relationship between octave and sestet is due to a change of tune in the sonnet’s original musical setting.

This opportunity for a change of tune may be taken in many different ways, though in nearly all of them the sestet provides some kind of consolidation of the material introduced in the octave. It ‘supports the octave as the cup supports the acorn’ (Lever, p. 7). A familiar example is Keats’s ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’. Note how the type 2 sestet encourages the tendency in a great many English writers of Italian sonnets to organize the sestet in distichs rather than in tercets. This tendency is even to be found in Keats’s octave:

Much have I travelled in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-browed Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific, and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise –

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

The beauty of this sonnet lies in the brilliant risk Keats takes of anticipating his boldest image by launching straight away into metaphors of voyaging. The octave exposes his limited experience of Greek literature with closed rhyme’s lulling musicality (sometimes a trap in English): the first quatrain deals with minor writers, ‘goodly states’ in their way, but surpassed in power by the ‘demesne’ of Homer which is the subject of the second quatrain. The theme has been fully stated and developed by the time Keats comes to ‘turn’, so that the sestet demands some bold conviction or surprise. The image of the astronomer acts as a buffer here. The discovery of a new planet is grand but rather vague. It enforces the sense of Keats’s receptivity and alertness, but it has little of the power of the final lines. These succeed because ‘stout Cortez’ is so specific, so far removed from the Mediterranean and so particularly appropriate figuratively to Keats’s main point, which is that just as Cortez (though Keats means Balboa) discovers a continent through an ocean (i.e. that he is not in Asia after all) so Keats discovers Homer through Chapman’s translation. This is what the ‘wild surmise’ is all about: the discovery in each case is indirect. Homer and the Pacific remain mysterious, essentially unknown.

It will be clear from this example (an overnight effusion) that the sonnet encourages intelligence, precision and density of imagery. For Keats, indeed, the sonnet was the key to his great Ode stanza. When we consider the substance and the depth of some more modern writers of sonnets (Mallarme, Rilke, Auden for instance) it will easily be supposed that the sonnet is capable of anything. Without denying the versatility that its continued use in our post-symbolist age has preserved for it, it should be remembered that its prime original use was as a love lyric. The artificiality still associated with the ‘Petrarchan’ sonnet was introduced by D’Arezzo, who imparted to it those inventions of Provençal love poetry which derived from the concetti of the Roman erotic poets and through them of the Greek epigrammatists. Guinizelli, Cavalcanti and Dante, and others of the dolce stil nuovo, reacted against this artificiality, and despite the lingering accusations implicit in the term ‘Petrarchanism’, Petrarch himself insisted on the genuineness of his passion for Laura, the housewife of Avignon whom he met ‘in the year 1327, exactly at the hour of prime on the sixth of April’, loved for twenty-one years and immortalized in his Rime. As love poetry the form was almost irredeemably overworke...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- GENERAL EDITOR’S PREFACE

- 1 The Italian Sonnet

- 2 The English Sonnet

- 3 Variants and Curiosities

- 4 Sequences

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Sonnet by John Fuller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.