![]()

Vegetal politics: belonging, practices and places

Lesley Head1, Jennifer Atchison1, Catherine Phillips2 & Kathleen Buckingham3

1Australian Centre for Cultural Environmental Research (AUSCCER), University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia, 2Centre for Critical and Cultural Studies (CCCS), University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia and 3Department Food, Forests and Water, World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, USA

Cultural geography has a long and proud tradition of research into human–plant relations. However, until recently, that tradition has been somewhat disconnected from conceptual advances in the social sciences, even those to which cultural geographers have made significant contributions. With a number of important exceptions, plant studies have been less explicitly part of more-than-human geographies than have animal studies. This special issue aims to redress this gap, recognising plants and their multiple engagements with and beyond humans. Plants are not only fundamental to human survival, they play a key role in many of the most important environmental political issues of the century, including biofuels, carbon economies and food security. In this introduction, we explore themes of belonging, practices and places, as discussed in the contributing papers. Together, the papers suggest new kinds of ‘vegetal politics’, documenting both collaborative and conflictual relations between humans, plants and others. They open up new spaces of political action and subjectivity, challenging political frames that are confined to humans. The papers also raise methodological questions and challenges for future research. This special issue grew out of sessions we organised at the Association of American Geographers Annual Meeting in New York in 2012.

The Forty Mile Scrub National Park in Far North Queensland offers a quick morning tea stop for travellers heading west towards the more popular Undara Volcanic National Park. If you have 5 minutes to spare, the 300-m walking track loop through the scrub is signed with points of interest. Jenny and PhD student Steph stopped here when heading west from Cairns in search of Rubber Vine (as part of the AUSCCER research project ‘The Social Life of Invasive Plants’). They found Bottle Trees, White Cedars and Burdekin Plums.

The ‘scrub’—dry rainforest or semi-evergreen vine thicket, is described in the signage as distinctly different to the lush coastal rainforests. Lower and more variable annual rainfall, combined with the hotter temperatures inland, limit and confine the distribution of rainforest species to small mineral rich basaltic soil patches—patches of rainforest in a sea of eucalypt savanna.

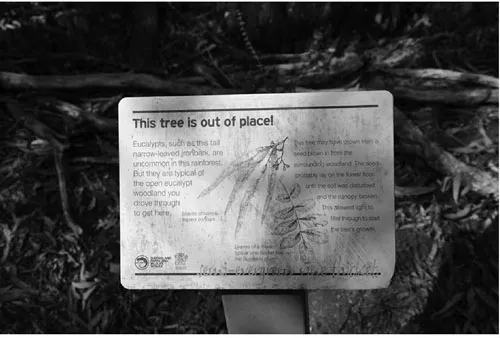

Some time ago, they learned, a seed, an interloper, survived and grew. ‘Out of place!’ (Figure 1). This tree now stands as a mature narrow-leaved iron bark in the middle of the rainforest. What does it mean for a tree to be ‘out of place’? Can a gum tree be out of place in Australia? Where does this plant belong?

Plant distributions are governed by tolerances, competition, disturbance and people. Life is possible for different species across water, mineral and temperature gradients. Life must also contend with fire regimes, herbivory, competition and so on. If a seed sprouts and a plant grows to maturity, it is tolerant of the conditions. If it survives and reproduces, it is ‘fit’. Plants assemble themselves amongst and in the thick of things. How then can this tree or indeed any plant—life becoming through relations, exchanging gases with the atmosphere, feeding and sheltering inhabitants, rooted firmly in the ground—be out of place? Fit, but not fitting?

The rainforest savanna boundary is not a line marked in the sand. There is a transition zone, there are thicker and thinner edges. Disturbance and gaps in the canopy come and go, creating momentary opportunity for some. These zones of belonging change through space, and time.

No Rubber Vine in sight, Jenny and Steph ventured further into the scrub beyond the walking track. Instead, they found a different invasive species and Weed of National Significance—Lantana (Lantana camara); thick, scratchy, impenetrable, rising over their heads and covered in ripening black berries. Other signs drew attention to the threat this intruder posed in the National Park, but its ongoing presence seemed an implicit acknowledgement of the stretched resources that make weed control in Northern Australia an impossible task. Wary of ticks, they headed out, feeling a bit out of place themselves.

Figure 1 Signage in Forty Mile Scrub National Park, Queensland. Photo: Jenny Atchison.

This anecdote encapsulates the themes of this special issue. The framing of particular plants as belonging or not in certain places is a culturally variable practice that pays only partial attention to the exuberance of planty life. Neither practices nor politics are understood here as purely human affairs, rather people, plants and many others are entangled in ways that both enhance and constrain each other’s lives.

Research into human–plant relations has a long and proud history in cultural geography and related disciplines, for example in the work of Carl Sauer (1952). Since Muir and Theoreau and the founding fathers of Western environmentalism articulated ‘wilderness’, it has become apparent that ‘landscapes are culture before they are nature; constructs of the imagination projected onto wood and water and rock’ (Schama 1995: 61). As Crosby (1986) noted in Ecological Imperialism, plants and our relationship to them are literally rooted in culture and history. In both rural and urban spaces, plants are allocated places, becoming weeds when they have ‘contempt for boundaries’ (Mabey 2010: 82). As plants move across time and space they become ‘aliens’, ‘invaders’ or ‘weeds’ in their new territories. The European domestication of landscapes has been widely articulated (Glacken 1967; Miller and Reill 1996; Thompson 2010), yet the relationality of plants occupying new landscapes and identities—what we think of as a ‘vegetative cosmopolitanism’ of plants—has yet to be given adequate attention.

The cultural landscapes tradition of considering human–plant relations has until recently been disconnected from conceptual advances in the social sciences, albeit cultural geographers have been at the forefront of those conceptual advances. Geographers and others have contested human exceptionalism and have used this to rethink nature–society relations, human identity and ethical engagement (Anderson 1997, 2008; Emel, Wilbert, and Wolch 2002; Haraway 2008; Whatmore 2002). The other-than-humans receiving most of the attention, however, have been animals.

The themes developed by such animal geographies have dominated, and arguably come to stand for, more-than-human geographies. Expanding our empirical investigations can bring us in new directions conceptually. Contributors to this collection join scholars attempting to go beyond ‘intuitive and benign encounters between stable, coherent, and large mammals’ (Lorimer and Davies 2010: 32), scholars who consider viruses, mosquitoes, bacteria (Hird 2010) and the indifferent earth itself (Clark 2011). Our aim with this special issue is to redress this gap, pushing our thinking to not only include but recognise plants and their multiple engagements with and beyond humans.

The concerns of this special issue are shared across a number of disciplines, and we hope this collection will advance cross-disciplinary conversations. In botany, philosophy and other parts of the humanities a body of research now makes the case for plants to be engaged with as subjects, rather than objects (Gagliano, Renton, Depczynski, and Mancuso 2014; Hall 2011; Marder 2011a, 2011b, 2012; Ryan 2011). A somewhat parallel conversation has been happening in anthropology. Notwithstanding its rich heritage of ethnographic study of the ways human societies engage with and conceptualise plants (Geissler and Prince 2009; Mosko 2009; Nazarea 2006; Rival 1998), multispecies ethnography (Kirksey and Helmreich 2010) now attempts to recognise the plants themselves, along with other nonhumans, as key players. Urban ecology and biogeography well recognise the plant worlds that our authors have approached, from a different direction (Pickett et al. 2011).

Indeed if cultural geography is here putting more plants into its analyses, biogeography and ecology have recently been getting better at putting people into theirs, for example through the concepts of anthropogenic biomes (or anthromes) (Ellis and Ramankutty 2008) and novel ecosystems (Hobbs et al. 2006; Hobbs, Higgs, and Hall 2013). The profound transformations and future uncertainties in the landscapes of the Anthropocene require such consideration (Lorimer 2012), and many of the signature challenges of the Anthropocene—invasives, food security, biodiversity conservation, species migrations—require the best possible understanding of human–plant relations.

The papers in this issue started life at a series of sessions we organised at the Association of American Geographers Annual Meeting in New York in 2012. In organising these sessions, we were aware that although the agency of plants has been increasingly demonstrated in contexts that include trees (Jones and Cloke 2002), gardens (Hitchings 2003, 2007; Power 2005), invasion (Atchison and Head 2013; Barker 2008; Ginn 2008), crops (Head, Atchison, and Gates 2012) and seeds (Phillips 2013); scholars had yet to fully respond, for plants, to Lulka’s (2009) call to attend more carefully to the details of nonhuman difference (Head and Atchison 2009). Lulka argued that there is a residual humanism in the use of the hybridity concept when ‘nonhumans’ are lumped as a singular entity. He insisted, instead, that what was required was a ‘thick hybridity’ in which an adequate sense of difference is maintained. Attention to the specific capacities of plants is important to understand the specifics of relationality and distributed agency in human–plant encounters; that categories and configurations of human entanglement with the nonhuman world are not pre-existing givens, but become and are worked out in a process of relation. Such relations occur across—indeed help constitute—different scales of space and time (Buckingham, Wu, and Lou 2013; Crosby 1986). However, plants are profoundly backgrounded in most of Western thought and life, and approaching human–plant encounters requires particular methodological sensitivities to their invisibility.

We were also conscious that more than a decade after Jones and Cloke (2002, 2008) important study of trees, their (2002: 4) comment that, while there had been considerable recent interest in animals and society, ‘flora … remains an even more ghost-like presence in contemporary theoretical approaches’, remained pertinent. Yet, as Patricia Pellegrini and Sandrine Baudry (2014) show in their beautifully illustrated paper herein, many plants come ‘unbidden’ into the cracks of our lives. Collectively, these papers show that attending to human–plant relations provides new insights into and framings of the political, and helps to rethink what it means to live with plants. Three of the papers take issue with the idea of cities as being somehow against nature, offering new ideas about what it means to be urban. The papers also provide fresh perspectives on questions of agency, identity, mobility, boundaries, place-making and ethics; they take themes that have well-established literatures oriented around humans and explore them through empirics of humans and plants working together, each paper pointing out new insights and applications for an agenda of rethinking human–plant geographies.

Pellegrini and Baudry’s study of street flora in Paris and Montpellier, France, provides interesting historical perspectives and important insights into the challenges of greening the densely packed cities of the future. They show for example how street level flower boxes have been used to constrain public behaviour deemed inappropriate. These authors go well beyond consideration of ‘greening’ as a planning concept meant to enhance urban liveability. Arguing that ‘cities can create their own flora’, the authors also recognise more co-production of plants and cities. On the one hand, they illustrate, with an eye for ordinary, informal spaces, the important role of ‘unbidden flora’ in urban places. On the other, they show how urbanised plants, some of them extremely tough, do not fit the dichotomised categories of wild or cultivated, but instead become ‘active agents’ in the making of the streets.

Melissa Poe, Joyce LeCompte, Rebecca McLain and Patrick Hurley (2014) focus on urban foraging for plants and mushrooms in Seattle, USA. Using a relational political ecology approach, they identify three constituent subfields of the concept of belonging—cultural belonging and identity, belonging and place and belonging and more-than-human agency. They show how some plant practices are authorised by environmental managers as belonging, specifically native plant restoration and indigenous historical ethnobotany. Other...