![]()

PART 1

Introduction to African Music

Africa astounds with its geographic expanse and its regional diversities. Because of its rich cultural heritage, we see today an extraordinary vitality in the performing arts. We begin with an introduction to African artistic expression and a survey of the history of our knowledge about African music.

![]()

Profile of Africa

Ruth M. Stone

Peoples and Languages

Subsistence and Industry

Transport and Trade

Social and Political Formations

Religious Beliefs and Practices

The African continent first impresses by its size: the second-largest of the continents of the world, it encloses more than 28 million square kilometers, spanning 8,000 kilometers from north to south and 7,400 kilometers from east to west. Islands dot the coasts, with Madagascar in the southeast being the largest.

Bisected by the equator, lying predominantly within the tropical region where thick rainforests grow, the continent consists of a plateau that rises from rather narrow coastal plains. Vast expanses of grassland also characterize its inland regions. The Sahara Desert dominates northern Africa, and the Kalahari Desert southern Africa. Vast mineral resources (of iron, gold, diamonds, oil) and deep tropical forests enrich the continent.

Peoples and Languages

The population of the continent constitutes only one-tenth of the world's people, though many urban areas and countries (like Nigeria) have a high density, counterbalancing vast regions of sparse population. Large urban areas have sprung up in nearly every country of Africa, with high-rise office buildings and computers part of the milieu. People cluster into nearly three thousand ethnic groups, each of which shares aspects of social identity. The most widely known reference work that classifies these groups is George Peter Murdock's Africa: Its People and Their Culture History (1959).

About one thousand distinct indigenous languages are spoken throughout Africa. Joseph Greenberg (1970) classifies them into four major divisions: Niger-Kordofanian, Nilo-Saharan, Hamito-Semitic, and Khoisan. The Niger-Kordofanian is the largest and most widespread of these, extending from West Africa to the southern tip of Africa; its geographical distribution points to the rapid movement of people from West Africa eastward and southward beginning about 2000 B.C. and extending into the 1600s of the common era.

Swahili, an East African trade language (with a Bantu grammar and much Arabic vocabulary), reflects the movements of peoples both within Africa and to and from Arabia. Bambara and Hausa, other trade languages (spoken across wide areas of West Africa), are but a few of the languages that show Arabic influence. In addition, the Austronesian family is represented by Malagasy, spoken on the island of Madagascar, and the Indo-European family by Afrikaans, spoken by descendants of seventeenth-century Dutch settlers in South Africa.

Following colonial rule in many countries, English, French, and Portuguese still serve as languages of commerce and education in the former colonies. Several languages of the Indian subcontinent are spoken by members of Asian communities that have arisen in many African countries, and numerous Lebanese traders throughout Africa speak a dialect of Arabic.

From the 1500s to the 1800s, trade in slaves produced a great outward movement of perhaps 10 million people from West and Central Africa to the Americas, and from East Africa to Arabia. A token return of ex-slaves and their descendants to Liberia during the 1800s represented a further disruption, as African-American settlers displaced portions of local populations. The long-term effects of this loss of manpower, and the attendant suffering it produced, have yet to be adequately understood. The movement of peoples, however, contributed to the formation of languages, such as the Krio of Sierra Leone and Liberian English of Liberia—hybrids of indigenous and foreign tongues.

Though indigenous systems of writing were not widespread in Africa, some peoples invented their own scripts. These peoples included some of the Tuareg and Berber groups in the Sahara and more than fifteen groups in West Africa, including the Vai and the Kpelle of Liberia, whose music is studied in this volume.

Subsistence and Industry

A majority of Africans engage in farming for their employment. In many areas, farmers use shifting cultivation, in which they plant a portion of land for a time and leave it to regenerate, moving to another plot. This form of agriculture is characteristically tied to a complex system of communal ownership. Increasingly, however, people and corporations, by acquiring exclusive ownership of large areas of arable land, are changing African land-use patterns.

International commerce has resulted in a shift from subsistence to cash crops: cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, sugarcane, tea, tobacco. The wage laborers who work with the crops migrate from their home villages, settling permanently or temporarily on large farms. Grassland areas throughout the continent support flocks of camels, cattle, goats, and sheep, and people there are predominantly herders, who frequently live as nomads to find the best grazing for their animals.

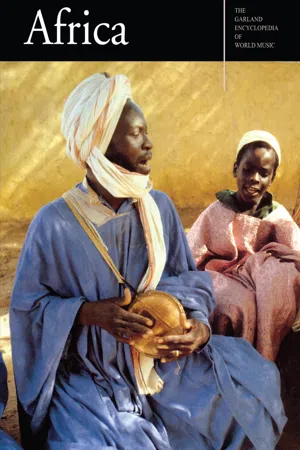

Typical of early African kingdoms were large retinues of royal musicians, who enhanced state occasions and provided musical commentary on events.

In many areas of Africa, rich natural resources—coal, copper, diamonds, gold, iron, oil, uranium—contribute to employment for notable sectors of the population. Processing these materials provides wages for workers and exports for the resource-rich nations.

Transport and Trade

For trade and travel, people have long moved across African deserts and savannas, and through African forests, but the intensity and speed of their movement increased with the building of roads, railways, and airports, particularly since the 1950s in many parts of the continent.

Suddenly, perishable fruits and vegetables could be shipped from interior farms to coastal urban areas. Taxis and buses built a lively trade shuttling people and goods up and down roads, from local markets to urban areas and back again. Manufactured goods were more readily available from petty traders and shopkeepers alike, and foods like frozen fish became part of the daily diet.

Among all that activity, cassettes of the latest popular music of the local country and the world became part of the goods available for purchase. Feature films of East Asian karate, Indian loveplots, or American black heroes became available, first from itinerant film projectionists, and by the 1980s from video clubs. On a weekly and sometimes daily basis, maritime shipping was now supplemented with air travel to Europe and the rest of the world.

Social and Political Formations

Several African kingdoms with large centralized governments emerged in the Middle Ages. Among these were Ghana in the West African grasslands area around the Niger River (A.D. 700-1200); Mali, which succeeded Ghana and became larger (1200-1500); and Songhai (1350-1600), which took over the territory of ancient Mali. Kanem-Bornu flourished further east in the interior (800-1800). In the forest region, Benin developed in parts of present-day Nigeria (1300-1800); Ashanti, in the area of contemporary Ghana (1700-1900); Kongo, along the Congo River (1400-1650); Luba-Lunda, in the Congo-Angola-Zambia grasslands (1400-1700); Zimbabwe, in southern Africa (1400-1800); and Buganda, in the area of present-day Uganda (1700-1900) (Davidson 1966:184-185).

Archaeological evidence is only now providing information about the full extent of indigenous African empires, fueled by long-distance trade in gold, ivory, salt, and other commodities. Typical of these kingdoms were large retinues of royal musicians, who enhanced state occasions and provided musical commentary on events. Benin bronze plaques, preserving visual images of some of these musicians, are in museums around the world.

Alongside large-scale political formations have been much smaller political units, known as stateless societies. Operating in smaller territories, inhabited by smaller numbers of people, these societies may have several levels in a hierarchy of chiefs, who in turn owe allegiance to a national government. At the lowest level in these societies, government is consensual in nature; at the upper levels, chiefs, “in consultation with elders and ordinary citizens, make decisions.

West Africa supports Poro and Sande (called secret societies by Westerners), organizations to which adults belong, and through which they are enculturated about social mores and customs. Children of various ages leave the village and live apart in the forest, in enclosures known as Poro (for men) and Sande (for women). There, they learn dances and songs that they will perform upon emergence at the closing ceremonies. Required parts of their education, these songs and dances are displayed for community appreciation at the end of the educational period. It is during this seclusion that promising young soloists in dance and drumming may be identified and specially tutored.

Kinship, though long studied by anthropologists in Africa, has proved complex and often hard to interpret. Ancestors are noted in formal lineages, which may be recited in praise singing and often reinterpreted according to the occasion and its requirements. Residence may be patrilocal or matrilocal, depending on local customs. And the extended families that are ubiquitous in Africa become distanced through urban relocation and labor migration, even if formal ties continue.

Settlements may take the form of nomadic camps (moving with the season and pasture), cities, towns, or dispersed homesteads along motor roads. They may also develop around mines, rubber plantations, and other work sites. Camps for workers who periodically travel home may become permanent settlements, where families also reside.

Religious Beliefs and Practices

Though indigenous religious beliefs and practices exhibit many varieties of practice, they share some common themes. A high, supreme, and often distant creator god rules. Intermediate deities become the focus of worship, divination, and sacrificial offerings. Spirits live in water, trees, rocks, and other places, and these become the beings through whose mediation people maintain contact with the creator god.

Indigenous religious practices in Africa have been influenced and overlaid by Christian and Islamic practices, among other world religions. New religious movements, such as aladura groups [FOREIGN-INDIGENOUS INTERCHANGE], have skillfully linked Christian religious practices with indigenous ones.

Elsewhere, Islam penetrated the forest region and brought changes to local prac-tices, even as it, too, underwent change [ISLAM IN LIBERIA]. The observance of Ramadan, the month of fasting, was introduced, certain musical practices were banned, and altered indigenous practices remained as compromises.

References

Davidson, Basil. 1966. African Kingdoms. New York: Time-Life Books.

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1970. The Languages of Africa. Bloomington, Ind: Research Center for the Language Sciences.

Murdock, George P. 1959. Africa: Its People and Their Culture History. New York: McGraw-Hill.

![]()

African Music in a Constellation of Arts

Ruth M. Stone

Concepts of Music

Concepts of Performance

Historic Preservation of African Music

African performance is a tightly wrapped bundle of arts that are sometimes difficult to separate, even for analysis. Singing, playing instruments, dancing, masquerading, and dramatizing are part of a conceptual package that many Africans think of as one and the same. The Kpelle people of Liberia use a single word, sang, to describe a well-danced movement, a well-sung phrase, or especially fine drumming. For them, the expressive acts that gives rise to these media are related and interlinked. The visual arts, the musical arts, the dramatic arts—all work together in the same domain and are conceptually treated as intertwined. To describe the execution of a sequence of dances, a Kpelle drummer might say, “The dance she spoke.”

Concepts of Music

Honest observers are hard pressed to find a single indigenous group in Africa that has a term congruent with the usual Western notion of “music.” There are terms for more specific acts like singing, playing instruments, and more broadly performing (dance, games, music); but the isolation of musical sound from other arts proves a Western abstraction, of which we should be aware when we approach the study of performance in Africa.

The arts maintain a close link to the rest of social...