![]()

chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Power electronics is a discipline increasingly involved in all processing stages of electric power, like generation, conversion, transmission distribution, and conditioning. But the power converters are restricted in their operational capacities by the switching devices, whose limitations are imposed by the physical characteristics of the semiconductor materials. In this sense, large amounts of research are taking place around the development of new semiconductor switching devices with larger voltage withstanding capabilities. However, the aim of increasing the working voltage of the converters with the existing power switches also finds its own way with the introduction of multilevel converters. These converters also have interesting additional features when compared to the classical two-level topologies, such as reducing the harmonic content of the synthesized voltage waveform. However, as the multilevel topologies increase the working voltage of the converters, they greatly increase the number of electronic devices or complementary energy storage elements (capacitors) in the circuit. This implies that the dynamics inside the converters have to be taken into account with their corresponding constraints, whereby the control strategies should consider them as part of the whole control target. Moreover, as the number of switches increases, so do the possible switching combinations, and more elaborated switching algorithms are necessary to meet the multiple constraints of the control problem (number of switches/number of redundant states, power density, unbalanced losses, reliability, etc.).On the other hand, in addition to the complexity of the converter’s control, today’s modern digital processing platforms allow the practical implementation of sophisticated control strategies at high speed.

All this represents a rich field of research around the study of existing multilevel topologies, the synthesis of new circuit configurations and control algorithms, as well as the dynamic interaction between the converters and the external systems in a wide variety of applications, such as electrical power conversion and conditioning.

1.2 Medium-Voltage Power Converters

The increasing energy demand encourages researchers to devise more efficient power processing systems. In this sense, electronic converters have gained significant prominence due to their versatility and fast dynamic response. Also, the development of advanced control techniques, and specially the technological evolution of power electronic switches, has made possible the operation of power converters in the medium-voltage range.

Nowadays, high-power converters can be found in numerous applications, such as AC drives for process control in the petrochemical, mining, and steel industries and also in traction technology for transportation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. The power processing in electrical networks at the distribution level for power quality improvement and also for the optimization of existing electrical infrastructure is a profitable application field [10,13,14,15,16,17]. Closely related to this field is the necessity of a grid-friendly interface of the renewable energy sources. In this discipline, the power converters are a key component because the control problems involve multiple and severe constraints from the grid and from the energy resource that can only be addressed through the highly versatile electronic converters.

The advancement of the gate turn-off thyristor (GTO) [18,25,26] and its evolution, the integrated gate-commutated thyristor (IGCT) [19,20,21,22,23,24], have given great impulse to the voltage source converters (VSCs) at medium voltage. This type of high-power semiconductor is more appropriate to be used in classical two-level VSCs. Meanwhile, the technology of the insulated gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) has given a strong push into the study of converters with multilevel topologies [8,23].

Technological evolution of power switches has allowed the development of motor drives up to 100 MW and static power compensators of about 10 MVA. Multilevel topologies have joined this evolution, ranging from 2.2 to 6.6 kV without the use of coupling transformers [10]. Moreover, they present some additional advantages over classical two-level topology, like the reduction of voltage harmonics and its consequent improvement of the processed power quality and also the increment of power density of the converters.

Nowadays, there is great interest around the study of voltage source multilevel converters (VSMCs), especially regarding new converter topologies and control methods. In this sense, different topologies were developed as industrial products with sinusoidal modulation techniques [26,27]. These techniques, which are well known for two-level converters, have been extended to multilevel converters [6,15,24,40,41], as well as a wide variety of advanced nonlinear control strategies, such as predictive control, among others.

1.3 Multilevel Converters

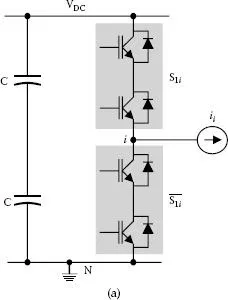

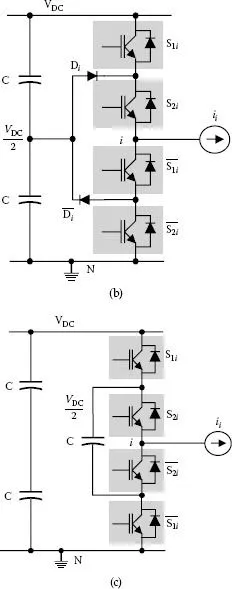

The AC output voltage of the two-level VSC is limited by the maximum voltage blocking capability of its switching devices. The use of VSC in medium-voltage applications without coupling transformers is severely constrained. So, a widespread technique to overcome these limitations consists of the series connection of the power devices, which allows distributing the blocking voltage [21]. Figure 1.1a shows one leg of a classical two-level VSC, whose switches are implemented with the series connection of two power devices. Considering that the series-connected devices have identical static and dynamic characteristics, the blocking voltage will be equally shared and each device should withstand VDC/2. This concept can be generalized to an arbitrary number of switching devices and allows an unlimited extension of the output voltage. However, this is not completely true due to natural spread of the electrical characteristics of the switching devices and their driving circuits. This introduces static and dynamic unbalances on the blocking voltages on each device during commutation. Therefore, the use of external snubber networks becomes essential to equalize the blocking voltages statically and dynamically. Integrated switching blocks and driving circuits with active overvoltage clamping and protections have also been developed in order to improve switching features [22]. However, they still have some drawbacks, like low utilization factor of the power semiconductors, increase of the switching losses, and need to duplicate or triplicate the redundancy of the blocks to handle the fault situation.

Figure 1.1 (a) Two-level converter with series-connected switches. (b) Neutral point clamp converter (three-level). (c) Flying capacitor converter (three-level).

The necessity to equalize the blocking voltage on the devices connected in series gave origin to the VSMC [4]. The first development in multilevel topologies has been the neutral point clamped (NPC) converter [28]. Figure 1.1b shows one leg of the NPC converter with four active switches that are connected to the midpoint of the DC bus through the clamping diodes (Di and ).

Each power semiconductor is an individual switch, and the upper switches (S(1,2)i) are activated in a complementary way with respect to those at the bottom of the leg . The effect of voltage limiting over the active switches is due to the clamping diodes Di and , which fix the blocking voltage to VDC/2. Another multilevel topology that allows voltage clamping on the power switches is the flying capacitor multilevel converter (FCMC) introduced by Meynard and Foch [29]. Figure 1.1c shows one leg of this converter where the flying capacitor is connected between the upper switches pair and bottom switches pair. The flying capacitor is supposed to have a constant voltage equal to the half of the DC bus voltage. Therefore, VDC/2 is the blocking voltage of all switches of the leg. However, it is necessary to implement an adequate switching sequence in order to keep the voltage of the flying capacitor [30].

A comparison between the topologies of Figure 1.1 shows that they have the same number of power semiconductors (without considering the clamping diodes of the NPC converter). However, they do not have the same number of switches. While the two-level VSC leg has two switches, both the NPC converter and FCMC topologies have four switches. The additional switches and their interconnection nodes are the key to increase the number of levels on the output voltage waveform. The classical two-level topology allows us to define only two possible voltages between nodes i and N (0 and VDC), and both the NPC converter and FCMC topologies are able to generate three voltage levels between nodes i and N: 0, VDC/2, and VDC. The appearance of an intermediate voltage level (VDC/2) allows reducing the harmonic contents on the output voltage. Hence, the multilevel topologies not only provide a clamping mechanism for the power switches, but also allow improving the harmonic quality of the synthesized output voltage.

Another voltage source multilevel converter that has interesting applications is the cascaded cell multilevel converter (CCMC) [7,24,31,32,33]. The simplest topology of the CCMC is shown in Figure 1.2 (five levels). It comprises two series-connected H-bridges. Each bridge imposes three voltage levels on the AC terminals (0, ±VDC/2), whereupon the switching combinations of both H-bridges yield to five output voltages: 0, ±VDC/2, and ±VDC.

1.3.1 Symmetric Topologies

All the VSMCs presented in the previous section have symm...