- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The book is about the colonization of the Sunderbans that began with the coming of the British. For two centuries, land-hungry peasants strove to transform the tidal forest vegetation into an agro- ecosystem dominated by paddy fields and fish culture. The construction of a permanent railroad led to the spreading of the co- operative movement, the formation of peasant organizations, and finally culminated in open rebellion by the peasants (tebhaga).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sundarbans by Sutapa Chatterjee Sarkar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Indian & South Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Sundarbans Folk Deities, Monsters and Mortals an Introduction

For naturalists, the Sundarbans have always held an irresistible charm.1 In common perception, the forests of the Sundarbans, located in the southernmost parts of West Bengal in India and south-western Bangladesh, remain synonymous with the Royal Bengal Tiger and, to some extent, the mangrove forests unique to South Asia.2 For a researcher, the choice of the Sundarbans as an area of enquiry presents some problems, because its popular culture has not yet been vigorously analysed. Its economy and tenurial patterns too require modern interpretation, free from the bias of imperial settlement reports.

The principal strands in the story of the region centre around the contest between the tiger and the forest dweller, in other words, the conflict between and co-existence of man and nature. This struggle took the form of reclamation, and of putting the forests to the plough.3 A few questions have been raised regarding what the region was like in the past—physically and socio-economically. What was the nature of the settlements and what kind of changes were brought about by the introduction of various policies of land reclamation? What were the other motives behind the schemes introduced by the British administrators such as the building of a port at Canning and Hamilton’s scheme of a co-operative?

Historical studies of the region have tended to be piecemeal in nature, and have generally formed a part of the revenue history of the Sundarbans. Pargiter and Ascoli’s accounts of this region were, for example, essentially government catalogues and compilations of land reclamation policies. Satish Chandra Mitra’s, Kalidas Dutta’s and A.F.M. Jalil’s accounts were worth mentioning. Hunter, Westland, Gastrell and Ralph Smyth’s reports were all more or less administrative accounts while Beveridge’s partial account focused on the Sundarbans of Bangladesh.

Subsequent secondary writings on the Sundarbans are either ethnographic, ecological or development oriented accounts, such as the works of Amal Kumar Das et al., A Focus on Sundarban, A.K. Mandal, R.K. Ghosh, Sundarban, A Socio-Bio-Ecological Study, Rathindranath De, The Sundarbans, Naskar, Guha Bakshi, Mangrove Swamps of the Sundarbans, Amal Kumar Das, Manish Kumar Raha, The Oraons of Sundarban, etc. Most of these talk about the flora and fauna, and the castes and tribes of the region. Others, separately, articulate the history of population movements, the Tiger Project,4 settlement patterns, etc. In addition to this, studies have been undertaken by NGOs active in this region.

More recently the region and its history formed the subject of an anthropological novel by Amitav Ghosh (The Hungry Tide)which captures evocatively some of the dimensions of the region’s historical experience, constituted by man, beast and nature. But there is perhaps no single account that comprehensively portrays the history of the region based on authentic archival material, available estate papers and less conventional sources like punthi and contemporary literature. This is what led me to undertake the present piece of work.

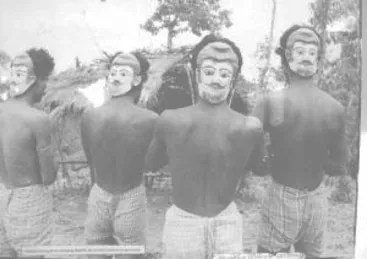

Masked Men in boat

Men wear masks at the back of their heads to ward off imminent threat from tigers when they go into the dense forests. These masks are caricatures of the human face meant to scare off the tigers.

Men wear masks at the back of their heads to ward off imminent threat from tigers when they go into the dense forests. These masks are caricatures of the human face meant to scare off the tigers.

The starting point of my study is the political change in Bengal in the mid-eighteenth century (1757), which brought the East India Company into the region as a new power. The Sundarbans acquired in 1757 with the 24 Parganas soon drew attention. An intensive study on the manner of land reclamation by the early colonial rulers and their motives illustrate a clear picture of the extent of colonial penetration into the life and functioning of rural India.

Down the ages there have been several efforts to reclaim forests and set up human habitation in this region. Before the advent of the British rule in India, such efforts were largely individual in nature and did not leave any lasting impressions on the physical and geographical configurations of the region.5 Those made during the rule of the British were largely successful in bringing in people of various origins into the Sundarbans.6>While they ultimately succeeded in reclaiming large tracts and settling down there for good, their efforts towards developing the region as a centre for generating revenue largely failed. Besides, there were a number of setbacks in developing a port at Canning and a co-operative farm at Gosaba. Yet, despite the slow pace of development compared to the rest of West Bengal, the face of the Sundarbans changed forever. Changes in settlement patterns and the stratification of society led to changes in human relations.

The purpose of this study is not to knit together accounts of all the islands of the Sundarbans into a story of total social and cultural experience but to give an elaborate description of the land reclamation policy in the districts of 24 Parganas, Khulna, Jessore and Bakarganj. While talking about reclamation, I will give a detailed account of the judge and magistrate of Jessore, Tilman Henckell a pioneer in the efforts to colonize the marshy land, as well as the work of Sir Daniel Hamilton (social reformer) who put much effort in settling and bringing change to the area. The focus will narrow down to Canning, Gosaba and Kakdwip (the West Bengal part of Sundarbans), where the changes in social relations were most visible.7 It is here that we see the establishment of a port, laying of railway tracks, formation of a co-operative and the emergence of socioeconomic conflict finally leading to the much-discussed peasant movement of Tebhaga.

The present work has been drawn from a variety of sources. Pargiter’s Revenue History of Sundarbans 1765–1870 and Ascoli’s Revenue History of Sundarbans 1870–1920 provided a basic introductory reading on the subject. Both these books deal exhaustively with British efforts at land reclamation in this area, from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. These two aforementioned books are essentially government documents and therefore somewhat monotonous and uninteresting. However, this does not undermine their importance as detailed accounts of land settlements and narratives of making arable the vast uncultivated tract of the Sundarbans. The accounts of Pargiter and Ascoli however do not have much to say about the origin, movement and condition of the actual settlers. Who were the people who came to settle in the newly reclaimed areas of the Sundarbans? How did they overcome natural obstacles? Were they given any material help except for the initial rent-free privilege? Was the British reclamation policy a genuine attempt at improving the conditions of the local people? These are questions, which will be taken into consideration during the course of this study. In addition to these sources there are survey settlement reports and old gazetteers of the 24 Parganas, Jessore and Bakarganj. Hunter’s Statistical Account of Bengal, Vol. I, is an important source material for this region. Among the several difficulties in researching the Sundarbans was the inadequacy of source material on the social and political circumstances, and their development in the region.

In terms of archival sources a considerable number of English correspondences in the West Bengal State Archives entitled Presidency Commissioner Sundarban Records have been examined. The Sundarban Records cover a short span of time (1829–1858). The correspondences mainly deal with the Letter Received and Letter Issued series of this particular tract of the country. The tedious task of consulting the Sundarban Records without any index was a long and futile exercise. Most of the proceedings were sent from Jessore and Bakarganj. The reason for this might be that the Sundarbans did not form a separate administrative unit with revenue, magisterial and civil jurisdiction of its own. The collectors of the 24 Parganas, Jessore and Bakarganj exercised concurrent jurisdiction with the local commissioner in the revenue matters of the Sundarbans.

The correspondences are not specific about the terms and conditions of the leases given to the settlers. Some of the letters deal with the boundary disputes between the neighbouring zamindars and the grantees of this region. There is a volume of information regarding the boundary lines, which were liable to frequent changes.8 A large number of the European residents of Calcutta were attracted by the prospect of largescale farming and availed of the opportunity. The Sundarban Records throw no remarkable light on the process of development of indigenous landlordism in the area.

The documents refer to only some names without any information regarding their rights and liabilities and, above all, their role in the reclamation process of the Sundarbans. Some of the correspondences give an account of the jamma/assessed in some areas after reclamation.9 This shows an increasing trend in the rate of assessment. Probably the rate of rent tended to increase with the development of land and cultivation. This makes it clear that some of the lands, thus cleared, yielded revenue to the state. It has been mentioned earlier that most of the documents of the Sundarban Records refer to reclamation activities only in the Jessore and Bakarganj areas. The process appears to have been facilitated by the availability of more sweet water and labour in the area. The reclamation of the 24 Parganas portion of the Sundarbans possibly had not attracted the attention of the authorities up to the second half of the nineteenth century. The Sundarban Records are inadequate for constructing a general history of land reclamation in the area from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. I therefore had to shift my attention to other sources covering the later period.

These were the correspondences of the Revenue Department, Land Revenue Branch and Home Political Department in West Bengal State Archives and National Archives, Delhi. Also significant were the letters exchanged between RabindranathTagore and Hamilton. These letters are kept at Rabindra Bhavana in Santiniketan. The original estate papers of Daniel Hamilton were found at Gosaba from a trustee member (the Late Dr Gopinath Burman) of the Hamilton Estate.

In addition to all these source materials, which are primarily in English, punthis and vernacular literature were taken into consideration to a large extent. The Sundarbans, by virtue of its exotic flora and fauna, exercised a powerful appeal to Bengali literary imagination, both traditional and modern. The punthi literature in Bengali verse, devoted to the gods and goddesses of Sundarbans, thrived in lower deltaic Bengal between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries. These deities were not the regular godheads of the Bengali pantheon. They were the gods and goddesses of woodcutters, honey gatherers, beeswax gatherers, boat builders and the most desperate cultivators. In fact, battling with the hostilities of nature was so overwhelming an aspect of the settlers’ lives in these areas that it led to the evolution of deities to whom they could appeal for refuge psychologically during difficult times. These punthis thus offer interesting insights into the characters of past human settlements in the Sundarbans. Other than the punthis, the Bengali prose literature of the twentieth century has also been taken into account. The changes which took place in this marshy jungle after land reclamation is clearly evident in prose. This literature reflected a different perspective and invested the region with a new meaning and a new set of symbols. In prose, nature became a differentiated category in contrast to the old form (punthi), where nature was part and parcel of the undifferentiated mythical and existential world. Religion had been the dominant element in the punthis, so much so that tigers were looked upon with fear and respect, as sons of Banabibi, the presiding deity of the forest. In the Bengali prose literature, by contrast, tigers were depicted al...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Maps

- Abbreviations

- 1. The Sundarbans: Folk Deities, Monsters and Mortals An Introduction

- 2. Fearsome Forests, Rising Tides: A Historical Geography of the Sundarbans

- 3. The Sundarbans in punthi Literature

- 4. Tilman Henckell: An Advocate of Colonial Paternalism

- 5. Land Reclamation from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century

- 6. Development of the Port at Canning and Gosaba Co-operative

- 7. Tebhaga in Kakdwip

- 8. The Sundarbans in Modern Bengali Fiction

- 9. The Mangrove and the Man: A Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index