For the purposes of image analysis and pattern recognition, one often transforms an image into another better represented form. Image-processing techniques have been developed tremendously during the past five decades and mathematical morphology in particular has been continuously receiving a great deal of attention because it provides a quantitative description of geometric structure and shape as well as a mathematical description of algebra, topology, probability, and integral geometry. Mathematical morphology has been proven to be extremely useful in many image processing and analysis applications.

Mathematical morphology denotes a branch of biology that deals with the forms and structures of animals and plants. It analyzes the shapes and forms of objects. In computer vision, it is used as a tool to extract image components that are useful in the representation and description of object shape. It is mathematical in the sense that the analysis is based on set theory, topology, lattice algebra, function, and so on.

The primary applications of multidimensional signal processing are image processing and multichannel time series analyses, which require techniques that can quantify the geometric structure of signals or patterns. The approaches offered by mathematical morphology have been developed to quantitatively describe the morphology (i.e., shape and size) of images. The concepts and operations of mathematical morphology are formal and general enough that they can be applied to the analysis of signals and geometric patterns of any dimensionality.

In this chapter, we first introduce the basic concept in digital image processing, then provide a brief history of mathematical morphology, followed by the essential morphological approach to image analysis. We finally take a brief look at the scope that this book covers.

1.1 Basic Concept in Digital Image Processing

Images are produced by a variety of physical devices, including still and video cameras, scanners, X-ray devices, electron microscopes, radar, and by ultrasound. They can be used for a variety of purposes, including entertainment, medical imaging, business and industry, military, civil, security, and scientific analyses. This ever-widening interest in digital image processing stems from the improvement in the quality of pictorial information available for human interpretation and the processing of scene data for autonomous machine perception.

The Webster’s dictionary defines an image as “a representation, likeness or imitation of an object or thing, a vivid or graphic description, something introduced to represent something else.” The word “picture” is a restricted type of image. The Webster’s dictionary defines a picture as “a representation made by painting, drawing, or photography; a vivid, graphic, accurate description of an object or thing so as to suggest a mental image or give an accurate idea of the thing itself.” In image processing, the word “picture” is sometimes equivalent to “image.”

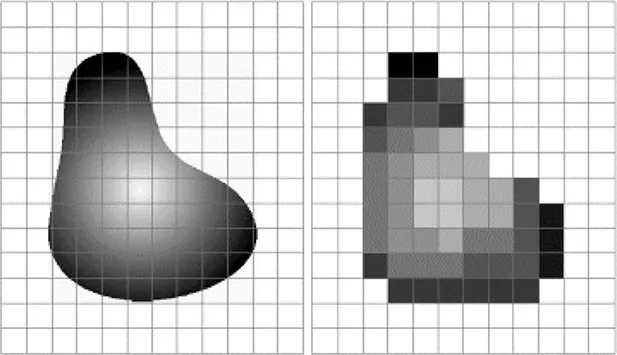

Digital image processing starts with one image and produces a modified version of that image. Digital image analysis is a process that transforms a digital image into something other than a digital image, such as a set of measurement data, alphabet text, or a decision. Image digitization is a process that converts a pictorial form to numerical data. A digital image is an image f(x, y) that has been discretized in both spatial coordinates and brightness (intensity). The image is divided into small regions called picture elements, or pixels (see Figure 1.1).

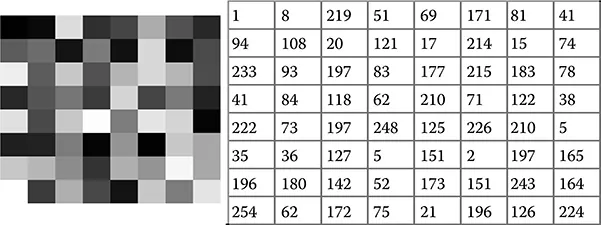

Image digitization includes image sampling [i.e., digitization of spatial coordinates (x, y)] and gray-level quantization (i.e., digitization of brightness amplitude). An image is represented by a rectangular array of integers. The image sizes and the number of gray levels are usually integer powers of 2. The number at each pixel represents the brightness or darkness (generally called the intensity) of the image at that point. For example, Figure 1.2 shows a digital image of 8 × 8 with one byte (i.e., 8 bits = 256 gray levels) per pixel.

The quality of an image strongly depends upon two parameters: the number of samples and the number of gray levels. The larger these two numbers, the better the quality of an image. However, this will result in a large amount of storage space because the size of an image is the product of its dimensions and the number of bits required to store gray levels. At a lower resolution, an image can produce a checkerboard effect or graininess. When an image of 1024 × 1024 is reduced to 512 × 512, it may not show much deterioration, but when further reduced to 256 × 256 and then rescaled back to 1024 × 1024, it may show discernible graininess.

FIGURE 1.1 Image digitization.

The visual quality requirement of an image depends upon its applications. To achieve the highest visual quality and at the same time the lowest memory requirement, one may perform fine sampling of an image at the sharp gray-level transition areas and coarse sampling in the smooth areas. This is known as sampling based on the characteristics of an image [Damera-Venkata et al. 2000]. Another method known as tapered quantization [Heckbert 1982] can be used for the distribution of gray levels by computing the occurrence frequency of all allowable levels. The quantization level is finely spaced in the regions where gray levels occur frequently, and is coarsely spaced in other regions where the gray levels rarely occur. Images with large amounts of detail can sometimes still have a satisfactory appearance despite a relatively small number of gray levels. This can be seen by examining isopreference curves using a set of subjective tests for images in the Nk-plane, where N is the number of samples and k is the number of gray levels [Huang 1965].

FIGURE 1.2 A digital image and its numerical representation.

In general, image-processing operations can be categorized into four types:

Pixel operations. The output at a pixel depends only on the input at that pixel, independent of all other pixels in that image. For example, thresholding, a process of making input pixels above a certain threshold level white, and others black, is simply a pixel operation. Other examples include brightness addition/subtraction, contrast stretching, image inverting, log transformation, and power-law transformation.

Local (neighborhood) operations. The output at a pixel depends not only on the pixel at the same location in the input image, but also on the input pixels immediately surrounding it (called its neighborhood). The size of the neighborhood is related to the desired transformation. However, as the size increases, so does its computational time. Note that in these operations, the output image must be created separately from the input image, so that the neighborhood pixels in calculation are all from the input image. Some examples are morphological filters, convolution, edge detection, smoothing filters (e.g., the averaging and the median filters), and sharpening filters (e.g., the Laplacian and the gradient filters). These operations can be adaptive because the results depend on the particular pixel values encountered in each image region.

Geometric operations. The output at a pixel depends only on the input levels at some other pixels defined by geometric transformations. Geometric operations are different from global operations in that the input is only from some allocated pixels calculated by geometric transformation. It is not required to use the input from all the pixels in calculation for this image transformation.

Global operations. The output at a pixel depends on all the pixels in an image. A global operation may be designed to reflect statistical information calculated from all the pixels in an image, but not from a local subset of pixels. As expected, global operations tend to be very slow. For example, a distance transformation of an image, which assigns to each object pixel the minimum distance from it to all the background pixels, belongs to a global operation. Other examples include histogram equalization/specification, image warping, Hough transform, spatial-frequency domain transforms, and connected components.

1.2 Brief History of Mathematical Morphology

A short summary of the historical development of mathematical morphology is introduced in this section. Early work in this discipline includes the work of Minkowski [1903], Dineen [1955], Kirsch [1957], Preston [1961], Moore [1968], and Golay [1969]. Mathematical morphology has been formalized since the 1960s by Georges Matheron and Jean Serra at the Centre de Morphologie Mathematique on the campus of the Paris School of Mines at Fontainebleau, France, for studying geometric and milling properties of ores. Matheron [1975] wrote a book on mathematical morphology, entitled Random Sets and Integral Geometry. Two volumes containing mathematical morphology theory were written by Serra [1982, 1988]. Other books describing fundamental applications include those of Giardina and Dougherty [1988], Dougherty [1993], and Goutsias and Heijmans [2000]. Haralick, Sternberg, and Zhuang [1987] presented a tutorial providing a quick understanding for a beginner. Shih and Mitchell [1989, 1991] created the technique of threshold decomposition of grayscale morphology into binary morphology, which provides a new insight into grayscale morphological processing.

Mathematical morphology has been a very active research field since 1985. Its related theoretical and practical literature has appeared as the main theme in professional journals, such as IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence; IEEE Transactions on Image Processing; IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing; Pattern Recognition; Pattern Recognition Letters; Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing; Image and Vision Computing; and Journal of Mathematical Imaging and Vision; in a series of professional conferences, such as the International Symposium on Mathematical Morphology, IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, and International Conference on Pattern Recognition; and professional societies, such as the International Society for Mathematical Morphology (ISMM) founded in 1993 in Barcelona, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), the International Association for Pattern Recognition (IAPR), and the International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE). The Morphology Digest, edited by Henk Heijmans and Pierre Soille since 1993, provides a communication channel among people interested in mathematical morphology and morphological image analysis.

1.3 Essential Morphological Approach to Image Analysis

From the Webster’s dictionary we find that the word morphology refers to any scientific study of form and structure. This term has been widely used in biology, linguistics, and geography. In image processing, a well-known general approach is provided by mathematical morphology, where the images being analyzed are considered as sets of points, and the set theory is applied to morphological operations. This approach is based upon logical, rather than arithmetic, relations between pixels and can extract geometric features by choosing a suitable structuring shape as a probe.

Haralick, Sternberg, and Zhuang [1987] stated that “as the identification and decomposition of objects, object features, object surface defects, and assembly defects correlate directly with shape, mathematical morphology clearly has an essential structural role to play in machine vision.” It has also become “increasingly important in image processing and analysis applications for object recognition and defect inspection” [Shih and Mitchell 1989]. Numerous morphological architectures and algorithms have been developed during the last decades. The advances in morphological image processing have followed a series of developments in the areas of mathematics, computer architectures, and algorithms.

Mathematical morphology provides nonlinear, lossy theories for image processing and pattern analysis. Researchers have developed numerous sophisticate...