![]()

1 Representative Democracy and the Problem of Institutionalizing Local Participatory Governance

Nils Herttingand Clarissa Kugelberg

Over the past few decades and throughout the world, numerous government- initiated experiments and attempts at directly engaging and including citizens have emerged as remedies for a variety of problems faced by modern democracies. On the level of local practice, these attempts have been given many names, such as citizen panels, deliberative fora, collaborative dialogues, etc. In the academic literature as well, the phenomenon is subsumed under many different headings—for instance, collaborative, deliberative, or interactive governance. In this book, we refer to this empirical phenomenon as local participatory governance; that is, government-sponsored direct participation between invited citizens and local officials in concrete arrangements and concerning problems that affect them. Hence the object of interest here is local governments’ invitations to participation, directed at individuals rather than interest groups or voluntary organizations.1

Participatory governance, we argue, may take many forms regarding the type of interaction and communication between participants within the specific participatory arrangement and regarding the relation and link between the specific arrangement and the more traditional representative structures. Some forms seem truly deliberative within the specific participatory arrangement, but have weak links to the regular policy process and representative institutions. Other forms seem to be tightly linked to representative institutions and policymaking, but have limited scope for free and open discussions within the participatory process.

This volume deals with attempts to establish processes, structures, and norms for such new modes of local participatory governance and collaboration between citizens, officials, and politicians in making and implementing local-level public policy. More specifically, the chapters of the volume explore and offer different perspectives on the same basic argument: Establishing and institutionalizing citizen participation in local policy processes on a more regular basis are not easy tasks because such efforts challenge or even contradict fundamental ideas about democratic accountability within representative democracies. As a collective piece of academic work, the book offers a critique of a too naïve and overoptimistic notion concerning the compatibility between traditional ideas and structures of representative democracy, on the one hand, and the contemporary participatory governance agenda described in the academic literature and promoted by activists, consultants, and policymakers, on the other. Both the theoretical and empirical contributions to the volume suggest that we should not expect stable and shared understandings, but instead continuous negotiations and re-negotiations of what the meaning and proper forms of participatory governance are in relation to representative institutions. Thus, it would seem that institutionalization of participatory governance is difficult to realize. Furthermore, the absence of solid institutionalization arguably obstructs realization of the assumed democratic and administrative promises of participatory governance.

Four Positions on Participatory Governance

Although the body of literature on participatory, interactive and collaborative governance has grown remarkably during recent years (e.g., Fischer 2012;Torfing et al. 2012; Fung 2015), the message regarding the phenomenon and its actual impact and political relevance is nevertheless contradictory and somewhat puzzling. On the one hand, it has often been argued that these new interactive or participatory modes of governance are “here to stay” and should be “taken seriously” (e.g., Sørensen and Torfing 2005; cf. Fung 2015). As indicated by the increasing number of sub-notions of participatory, collaborative, deliberative, or interactive modes of governance, this group of scholars would seem to be suggesting that there is a fundamentally new political order “out there” that needs to be identified, described, and explained. Although they all share the view that there is a distinct, new interactive or participatory dimension to governance, whether this is due to a more “organic” and evolutionary bottom-up process or a consequence of more strategic top-down institutional reform is a topic of debate. Some have inferred more decentralized or even uncontrolled modes of collective problem-solving (cf. Ansell 2011), and others have introduced concepts such as meta-governance (Torfing et al. 2012: 62ff.) or network management (Koppenjan and Klijn 2004) as a way of recognizing the new and more indirect role of state control in developing such new interactive modes of governance.

On the other hand, scholars have also informed us that this is merely an academic trend among researchers trying to create a niche for themselves or a new fancy product in consultants’ portfolios. Regarding effects on the political order, it has been argued that participatory governance is a marginal phenomenon, often resulting in temporary projects with ambiguous mandates, relegated to the periphery of decision-making processes, with trivial ambitions and hence limited possibilities to deliver “in practice” what is promised “in theory” (Lang 2007; Fung 2015). Regarding influence and power, research on quite a few European experiences has suggested that participatory processes seem to have little political impact—on policy, implementation, or outcomes—because their agendas are limited to local issues (Sintomer and de Maillard 2007; Brannan, John and Stoker 2007; Font and Galais 2011). According to this line of argument, participatory reforms at the local level are “a drop in the bucket” (cf. Taylor 2011: 13). Participatory modes of governance seem to be unable to gain a foothold, and the new, emergent participatory, interactive, or collaborative order still seems embryonic decades after it was first discussed in the literature. From this perspective, notions such as participatory or interactive governance have limited descriptive value. According to this argument, beyond the academic discourse and beyond narrow and restricted projects, there is no established praxis of what could be described as participatory governance.

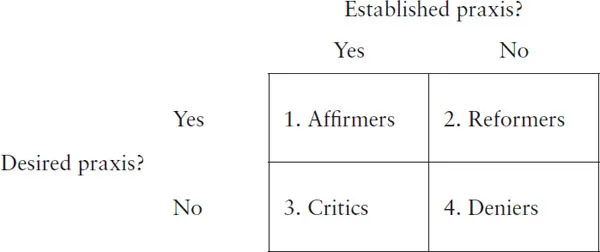

Describing is one thing, evaluating something else. Besides divergent descriptions of the phenomenon’s magnitude, at least two different normative appraisals of it have been made. In the view of some scholars, the negligible impact of participatory governance is regrettable. For them it suggests that the democratic system is still dominated by privileged groups with regard to input to the political machinery and lost opportunity to better use the information and resources in the local community for improved problem-solving capacity during the output phases of the policy process. According to others, however, the conclusion is rather that the parliamentary chain of representative democracy and its institutional mechanisms to secure transparency and political equality are not being threatened or challenged (cf. Christiansen and Togeby 2006). Hence, in order to provide overview, we can cross the two dimensions established and desired participatory governance to arrive at four positions on participatory governance (cf. Figure 1.1 below).

Affirmers and reformers share the view that there is a need for new and more participatory and interactive modes of governance. To be more specific, this argument comes in two different versions: the democratic revitalization rationale and the administrative effectiveness rationale. The democratic revitalization rationale begins with a more or less explicitly stated idea about a “democratic deficit” (Dalton, Scarrow and Cain 2004; Somerville 2011; Warren 2009) and increasing gaps between citizens, elected politicians, and civil servants. From such a perspective, participatory governance includes “democratic innovations” (Smith 2009) driven by attempts to “renew,” “deepen” (Fung and Olin Wright 2001), or “invest in” (Sirianni 2009) democracy in order to better safeguard democratic core values such as political equality, deliberation, and democratic accountability. In a European context, the most radical version of the democratic rationalization rationale is perhaps only relevant for counterfactual propositions and arguments. According to this position, participatory reform is more than a repair kit for representative democracy. Individual participatory reforms are best interpreted as strategies to change and transform the fundamental norms and institutions of democratic governance (Hirst 2000). Based on such a transitional (Klijn and Skelcher 2007) rationale, participatory and self-regulated network fora are seen as the new core institutions of democracy, and politicians play a more background role as “meta-governors,” responsible for securing the participatory infrastructure from a distance (Sørensen and Torfing 2009; Torfing and Triantafillou 2011).

Figure 1.1 Four positions on local participatory governance.

The popularity of participatory reform does not seem, however, to only be a consequence of caring about democracy. The introduction of more direct forms of participation is also defended according to an administrative effectiveness rationale by referring to increased problem-solving capacity and improved effectiveness in the administrative phases of the policy process. For instance, according to “network governance” theory (Kickert, Klijn and Koppenjan 1997; Hertting and Vedung 2012), the primary aim of citizen participation is to mobilize the crucial resources of interdependent actors in order to arrive at innovative solutions to complex policy problems. Given perceptions of the uncertainty of many contemporary policy issues, citizens’ knowledge and information about the possible consequences and outcomes of different interventions become crucial governance resources (Innes and Booher 1999; Koppenjan and Klijn 2004; Wagenaar 2007).

Although both affirmers and critics share the belief that there is something novel out there to be described in terms of new and more interactive modes of governance, they make opposite normative evaluations of the tendency. Participatory reforms may have democratization motives, but critics claim that implementing these reforms nevertheless entails democratic risks. Attempts to institutionalize participatory arrangements jeopardize values such as democratic accountability and transparency, which are better achieved with the traditional structures of representative democracy. Ambiguous and vague rules concerning the positions, jurisdiction, and boundaries of participatory arrangements will not only undermine democratic accountability, but also make it more difficult to implement policies based on democratic mandates; innovations aimed at including new and empowering weak participants have a tendency to attract people who are already engaged in politics. Rather than creating more equal opportunities for political participation, they produce new arenas for already existing local political elites (cf. Abers 2001) and a more centralized civil society (cf. Hertting 2009).

Among the critics we find a sub-group of observers—the cynics—who not only question the outcomes, but also the intentions of participatory governance initiatives. From such a position, the rationale behind participatory reforms is rather shady. Participation is not a matter of democratization or of making governance more effective. Instead it is promoted as a top-down strategy to avoid or at least spread responsibility in politically tricky situations or to camouflage unpopular policies and reforms (cf. Swyngedouw 2005). In other words, framing policy issues as complex and, accordingly, requesting the participation of wider groups in society may also be a convenient strategy for dealing with problems when the substantive policy solutions are too politically costly.

According to the deniers, the normative critique of participatory governance is more academic in nature. Using Albert O. Hirschman’s terms, participatory governance reforms are merely futile (Hirschman 1991: 43) attempts to change the political order. And for the deniers, this futility is for good reason. Participatory reform is not desirable, and the attempts observed are so marginal and peripheral in nature that they cannot really be taken seriously. They can simply be neglected and denied.

The reformers, finally, are troubled about the marginal effects they feel participatory governance structures have. In relation to the “rhetoric of reaction” (Hirschman 1991) among deniers and critics, the reformers point to something like a “nirvana fallacy” (Rothstein 1998): It is easy to argue against the real-world practices of participatory governance using an ideal model of a perfect representative system of democracy as the yardstick. From the reformers’ point of view, the existing practices of democracy are not only far from perfect, but also unlikely to be restored within the “protective paradigm” of election-centered representative democracy (cf. Stoker 2011: 34ff.). If representative democracy was perfect and problem free, they claim, no participatory reform movement would have emerged in the first place (cf. Fung 2012). That is, in contexts where we find deficits and problems in democratic input or accountability in the policy process, the actual function of participatory governance arrangements is different than in a context where the chain of representative governance runs perfectly and smoothly. The idea of the reformer is “that some types of governing structures do not have the same legitimacy as before, so there is a need to fill out the space between state and individual” (Brannan, John and Stoker 2007: 8).

Representative Democracy and Local Participatory Governance

In this volume, we have no outright normative agenda. Our aim is to provide a better understanding of the challenges to reforming local governance in a more participatory direction. In that sense, we formulate our research problem based on the reformers’ perspective, and we focus on the problem of integrating and institutionalizing participatory arrangements within the overall framework of representative institutions. However, as will be explained and elaborated later, we believe that there are good reasons to claim that establishing and institutionalizing participatory governance is a tricky business.

We are not the first to point out the institutionalization problem of participatory, collaborative, or interactive modes of governance (Skelcher, Sullivan and Jeffares 2013; Torfing et al. 2012; De Souza Briggs 2008; Klijn and Skelcher 2007). A number of preconditions for establishing stable and meaningful structures for participatory governance have been suggested before: decision authority needs to be decentralized or devolved to local levels; linkages between local levels of participation and more central levels of control need to be arranged; central strategies to support local participation need to be developed and implemented (cf. Fung and Olin Wright 2001). Mutual dependencies and a shared need for exchanges between citizens, administrators, and politicians are stressed; if politicians and administrators believe they can implement desired outcomes on their own, extending invitations to citizens to participate tends to involve only empty words and symbolic gestures (cf. Ansell and Gash 2008).

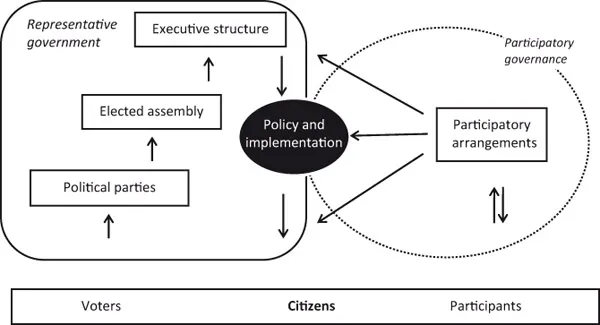

As already indicated, the book chapters offer another argument: Using different approaches and starting from different local contexts, the contributors suggest that the problem has to do with the relation between the ideas, institutions, and practices of participatory governance, on the one hand, and the ideas, institutions, and practices of representative democracy, on the other. This argument goes beyond the general notion of the inertia of institutional change. As illustrated in Figure 1.2, it highlights instead the practical implications of normative tensions between different notions of democratic governance and democratic accountability, stressing that it is too often the case that the idea that participatory arrangements and representative democracy are supplementary or mutually supportive is introduced without taking such normative and hence institutional tensions seriously (see however Skelcher, Sullivan and Jeffares 2013; Klijn and Skelcher 2007).