- 510 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Principles of Embryology

About this book

First published in 1956, this book was considered the first comprehensive and unitary work on the subject since 1934. It provides an analysis of the relations between genetics and epigenetics, between genes and their effects. The book will be of interest to ebryologists, but also to more general biologists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Principles of Embryology by C. H. Waddington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE FACTS OF DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER I

THE SCIENCE OF EMBRYOLOGY

1. The place of embryology among the biological sciences

The core of the science of embryology is the study of developmental phenomena in the early stages of the life-history of animals. It is, however, impossible to discover any general and important dividing line between the embryonic and later stages of development, and there is no good reason to exclude from the purview of the subject those processes of development which take place in stages later than the strictly embryonic. It is best, in fact, to understand the word ‘embryology’ as referring to all aspects of animal development, in which case it will include, among the peripheral fields in which it shades off into other sciences, some phenomena which may also be considered as parts of endocrinology or of genetics.

From whatever point of view one regards the biological sciences, the study of development will inevitably be found to take a central position among them. If one attempts to view biology as a whole, there are broadly speaking two main approaches which one can adopt; either one tries to formulate a general system which will exhibit all the major aspects of animal existence in their proper relation to one another; or one searches for a theory of ultimate units which could play the same role for biology as the electrons and similar particles do for physics and chemistry.

From the first, or synthetic, point of view, the most fundamental character of living things is the way in which time is involved in their existence. An animal functions from minute to minute or from hour to hour, in feeding, digesting, respiring, using its muscles, nerves, glands and so on. These processes of physiological functioning may be repeated within periods of time which are short in comparison with the lifetime of an individual animal. But there is an equally important set of processes, of a slower tempo, which require appreciable fractions of the life-history and are repeated only a few times, if at all, during one life-cycle; these constitute development. Still longer-term processes are those of heredity, which can only be realised during the passage of at least a few generations and which form the province of genetics. And finally, no full picture of an animal can be given without taking account of the still slower processes of evolution, which unfold themselves only in the course of many lifetimes .From this point of view, then, embryology takes its place between on the one side and genetics on the other.

As a matter of historical fact, the biological sciences at the two ends of the time-scale—those of physiology in the broad sense on the one hand, and of evolution on the other—have been more thoroughly developed than the two sciences of embryology and genetics which come between them. The volume of information available about physiological phenomena is immense; their relevance to medicine and animal husbandry has given them practical importance, and the relative ease with which they can be envisaged in physicochemical terms has made them seem intellectually attractive. The study of evolution, which was until recently only slightly less voluminous, derived its impetus from the feeling that Darwin’s work has provided the essential thread which was needed to link all aspects of biology together. Between these two huge masses of biological science, embryology and genetics are rather in the position of the neglected younger sisters in a fairy tale.

At the present time it looks rather as though the fairy tale will have the conventional ending, and the elder sisters find themselves in difficulties from which the younger ones will have to rescue them. This is becoming most apparent in connection with evolutionary studies; their enormous expansion in the past has been mainly by the essentially non-experimental methods of comparative anatomy and taxonomy, and it is already clear that little progress can be made towards an understanding of the causal mechanisms of evolution without the aid of genetics and to a lesser extent of embryology. And even physiology finds itself more and more led to the recognition that structural considerations are of the utmost importance for the functioning of biological systems; and this realisation brings it into close contact with embryology, which of all the biological sciences is most concerned with questions of structure and form.

The central position of embryology is perhaps better appreciated when one regards biology from the other viewpoint, which seeks to discover some category of ultimate units. It is clear that the unit which underlies the phenomena of evolution, and of the short-term heredity which constitutes genetics in the narrow sense, is the Mendelian factor or gene. But any theory based on our present knowledge of genes has perforce a most uncomfortable gap in it at the place where it should explain how they control the characters of the animals in which they are carried. For physiology, the basic unit is the enzyme. We know that the formation of most, if not all, enzymes is controlled by genes; in fact it is not unplausible to suggest that genes are simply a particularly powerful class of enzymes. But here once again we find ourselves confronted with that most lamentable deficiency, our lack of knowledge of exactly what genes do and how they interact with other parts of the cell in doing it. But whatever the immediate operations of genes turn out to be, they most certainly belong to the category of developmental processes and thus belong to the province of embryology. This central problem of fundamental biology at the present time is of course being attacked from many sides, both by physiologists and biochemists and by geneticists; but it is essentially an embrylogical problem.

It is unlikely that the methods of classical descriptive or experimental embryology will suffice to bring any solution to the problem of the genetic control of development. Neither will the conventional breeding methods of classical genetics, or, in all probability, the normal techniques of biochemistry and physiology. A general textbook of embryology can, however, not be confined to those novel techniques of investigation which, at any given time, seem most likely to lead to major advances in understanding. New methods can usually only be applied to old material; and new ideas do not suddenly emerge full-fashioned, as Aphrodite was born from the chaotic sea; they are built up laboriously on the foundation of previous work. Thus this book will attempt to describe, in the abbreviated and simplified outline which considerations of space impose, the general framework of embryological science within which the attack on the fundamental problems has to be made. Those problems cannot always be in the forefront, but the importance of the various aspects of embryology will be better appreciated if one has a clear realisation of the nature of the goal towards which our expanding knowledge is advancing.

2. An outline of development

Since all animals are in some way related, through the processes of evolution, there are some similarities in their various forms of development. One can, in fact, sketch a broad outline of the early stages of development which applies, roughly at least, to all the animal phyla. This can best be described in terms of a series of stages:

Stage 1. The maturation of the egg. The period during which the egg-cell is formed in the ovary might be thought to come, as it were, before embryology begins, but actually it is of great importance. It is, of course, the time when the meiotic divisions of the nucleus occur and the number of chromosomes is reduced to the haploid set. Further, the egg is pumped full of nutritive materials of various kinds, collectively known as ‘yolk’ (in the broad sense of that word); there are usually special ‘nurse cells’, closely applied to the growing egg in the ovary, which are concerned in supplying these stores of yolk. Finally, and most important of all, it is during this time that the egg-cell acquires its basic structure, which provides the framework for all the elaboration which will occur in later development. This basic structure always involves a polar difference by which one end of the egg becomes different to the opposite end; these are the so-called animal and vegetative poles. There may be also a second difference, distinguishing the dorsal from the ventral side and thus defining a plane of bilateral symmetry; perhaps indeed there is always some trace of such a difference, though it is not always well marked or very stable. Lastly one may mention a difference of another kind, between a cortex which forms the outer surface of the egg and an internal cytoplasm which is usually more fluid. We shall see that all these three elements of structure—the animal-vegetative axis, the dorso-ventral axis and the cor-tex-cytoplasm system—play very important roles in development.

Stage 2. Fertilisation. This stage involves two important processes; the union of the haploid nucleus carried by the egg with that of the sperm, and the ‘activation’ of the egg, which causes it to begin dividing and thus to pass into the next stage. These two processes are distinct from one another, and we shall see that activation can happen without any union of the nuclei taking place.

Stage 3. Cleavage. The egg-cell becomes divided into smaller and smaller parts by a process of cell division. There are many different patterns in which such cleavage can occur, and it is greatly influenced by the presence of large quantities of yolk.

Stage 4. The blastula. Cell division continues throughout the greater part of the embryonic period, but the stage of cleavage is said to come to an end when the next important developmental event occurs. This event is gastrulation, and the embryo which is just ready to start gastrulating is spoken of as a blastula. In its most typical form the blastula consists simply of a hollow mass of smallish cells; these have been produced from the egg by cell division, and the hollow space in the middle of the mass is formed by the secretion of some fluid material into the centre of the group. When there is a considerable quantity of yolk, the blastula becomes asymmetrical, the cells which contain a high concentration of yolk being larger than the others. In the extreme case, such as in the eggs of birds, the yolky end (the vegetative pole) does not cleave at all, and the blastula becomes reduced to a small flat plate floating on the upper pole of the yolk; this is known as a blastoderm.

Stage 5. Gastrulation. In a short and extremely critical period of development, the various regions of the blastula become folded and moved around in such a way as to build up an embryo which contains three more or less distinct layers (only the inner and outer layers appear in coelenterates and lower forms). These three fundamental layers are known as (i) the ectoderm, which lies outermost, and will develop into the skin and the neural tissue, (ii) the endoderm, which lies innermost and will form the gut and its appurtenances, and (iii) the mesoderm, which lies between the other two, and will form the muscles, skeleton, etc. The foldings by which these layers are brought into the correct relation with one another are very different in different groups, as they are bound to be since the blastulae from which they start may not have the typical spherical shape, particularly when there is much yolk in the egg. But in spite of differences in the process of gastrulation, the situation to which it leads—one in which there is an outer, an inner and a middle layer—is rather uniform in all groups.

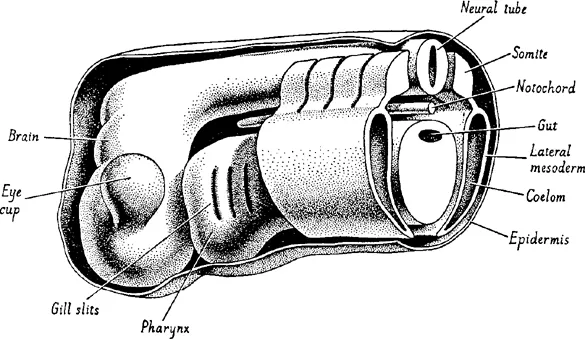

Stage 6. Formation of the basic organs. Soon after gastrulation the fundamental pattern of the embryo begins to appear. In most cases, the organs which arise are ones which will persist throughout the remainder of development, and will form the most essential organs of the adult animal; but in some animals the embryo at first develops into a larva, forming organs which require radical alteration before the adult appears. There are, of course, too many types of adult or larva in the whole animal kingdom for it to be possible to give a single scheme of basic organs which can apply to them all, but it is perhaps worth while to indicate the general pattern of all the various types of vertebrates. Such a scheme is shown in Fig. 1.1. We see that the ectoderm forms, firstly, the skin which covers the whole body, and secondly a thickened plate which folds up to form first a groove and finally a tube which sinks below the surface and differentiates into the central nervous system. (At the boundary between the neural and skin parts of the ectoderm, cells leave the ectodermal sheet and move into the interior of the embryo; this ‘neural crest’, which forms nervous ganglia and other organs is not shown in the Figure.) The sheet of mesoderm becomes split up longitudinally into a series of zones. Under the midline of the embryo is a long rod-like structure, the notochord, which is the first skeletal element to appear. On each side of this the mesoderm is thickened and transversely segmented so that it takes the form of a series of roughly cuboidal blocks, which are known as somites, and which give rise to the main muscles of the trunk as well as the inner layers of the skin. Laterally on each side of the somites there is a zone of mesoderm which will later produce the nephroi or kidneys, and laterally again more mesoderm which is not transversely segmented and which is destined to give rise to the limbs and the more ventral muscles and sub-epidermal skin. Finally, in the most inner recesses of the embryo, the endoderm becomes folded into a tubular structure which is the beginning of the gut or intestine. The formation of these organs always begins earlier in the anterior end of the embryo than in the posterior.

FIGURE 1.1

To illustrate the basic structure of a generalised vertebrate embryo.

To illustrate the basic structure of a generalised vertebrate embryo.

After these basic elements in the adult structure have been roughed out, there remains, of course, much to be done in adding the details, but the phenomena differ so much in the various phyla that there is no point in trying to describe more stages of general application.

3. Phylogenetic theories of embryology

Until fairly recently, the main theoretical concern of embryologists has been to find a guiding principle which would allow them to arrange the enormous mass of descriptions of developmental changes into some sort of ord...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Part One The Facts of Development

- Parr Two The Fundamental Mechanisms of Development

- Bibliography

- Author Index

- Subject Index