eBook - ePub

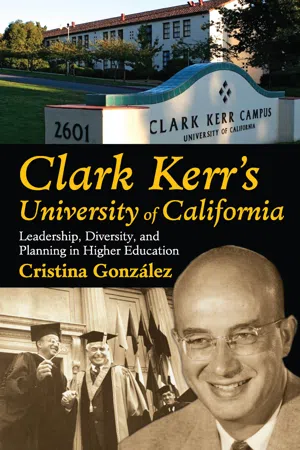

Clark Kerr's University of California

Leadership, Diversity, and Planning in Higher Education

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clark Kerr's University of California

Leadership, Diversity, and Planning in Higher Education

About this book

This volume provides an intellectual history of Kerr's vision of the multiversity, as expressed in his most famous work, The Uses of the University, and in his greatest administrative accomplishment, the California Master Plan for Higher Education. Building upon Kerr's use of the visionary hedgehog/shrewd fox dichotomy, the book explains the rise of the University of California as due to the articulation and implementation of the hedgehog concept of systemic excellence that underpins the master plan.Arguing that the university's recent problems flow from a fox culture, characterized by a free-for-all approach to management, including excessive executive compensation, this is a call for a new vision for the university—and for public higher education in general. In particular, it advocates re-funding and re-democratizing public higher education and renewing its leadership through thoughtful succession planning, with a special emphasis on diversity.Gonzalez's work follows the ups and downs of women and minorities in higher education, showing that university advances often have resulted in the further marginalization of these groups. Clark Kerr's University of California is about American public higher education at the crossroads and will be of interest to those concerned with the future of the public university as an institution, as well as those interested in issues relating to leadership, diversity, and succession planning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Clark Kerr's University of California by Cristina Gonzalez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralPart I

Exploring Clark Kerr’s Thinking

1

Hedgehogs and Foxes

Chapter 9 of the 2001 edition of Kerr’s classic work The Uses of the University, titled “The ‘City of Intellect’ in a Century for the Foxes?” concludes with a very interesting comment about leadership. Using an ancient animal metaphor, Kerr defines two types of leaders: the fox and the hedgehog. The seventh century B.C. Greek poet Archilochus wrote: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing” (2001a: 207). In his famous work The Hedgehog and the Fox, Isaiah Berlin (1953) used this metaphor to distinguish between writers such as Plato, Dante, Pascal, and Dostoevsky, who “relate everything to a single central vision,” and those who “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory,” including Aristotle, Shakespeare, Montaigne, and Pushkin (1). According to Kerr, hedgehogs are centripetal and foxes are centrifugal:

The hedgehog tends to “preach”—“passionate, almost obsessive;” while the fox is “cunning”—clever, even sly. Order versus chaos; unity versus multiplicity; the big vision versus adjusting to miscellaneous unanticipated events; certainty versus uncertainty. (Kerr, 2001a: 208)

While Berlin used this concept to shed light on Tolstoy, whom he saw as a fox trying to be a hedgehog, Kerr employed it to distinguish between two different kinds of leaders: the shrewd fox and the visionary hedgehog. Each deals with multiplicity in a different way: the fox, following his instinct, picks one option and runs with it, whereas the hedgehog uses his intellect to create a holistic model out of many fragments.

Kerr had previously discussed other terminologies, such as Hutchins’ (1956) “troublemaker” and “officeholder,” Harold W. Dodds’ (1962) “educator” and “caretaker,” Frederick Rudolph’s (1962) “creator” and “inheritor,” Henry M. Wriston’s (1959) “wielder of power” and “persuader,” and Eric Ashby’s (1962) “pump” and “bottleneck,” as well as James L. Morrill’s (1960) “initiator” and John D. Millet’s (1962) “consensus-seeker” (2001a: 23-24). In recent times, other terms have been used to express the same distinction. For example, Warren G. Bennis and Burt Nanus (1985), Joyce Bennett Justus, Sandria B. Freitag and L. Leann Parker (1987), and John W. Gardner (1990) distinguish between “leaders” and “managers,” and James McGregor Burns (1978) writes about “transformational leaders” and “transactional leaders,” a very successful terminology that has been explained and expanded by Bernard M. Bass (1985), who points out that the best leaders are both transformational and transactional, and the worst are neither.

The hedgehog/fox terminology has been used by a number of scholars in the last decade to describe the same dichotomy. Hedgehogs are transformational leaders, while foxes are transactional ones. There are writers who do not favor one type over the other. For example, Stephen Jay Gould (2003) discusses two equally good kinds of scholars: foxes, who explore many different fields, and hedgehogs, who work on a single, big project. Philip E. Tetlock (2005) studies two types of forecasters: foxes, who are right more often on short-term predictions, and hedgehogs, who when proven right about long-term forecasts, are very right. Hedgehogs’ big successes cancel their equally big mistakes, while foxes blend perspectives and “do intuitively what averaging does statistically” (179). Some scholars favor the fox. For instance, Claudio Véliz (1994) used this terminology to distinguish between the Spanish and British Empires in the Americas, attributing the ultimate success of the latter to its fox-like innovative shrewdness, which prevailed over the old-fashioned hedgehog vision of the former. Other thinkers prefer the hedgehog. Jim Collins (2001, 2004 [1994], 2005, 2009), for example, theorizes that only companies with a “hedgehog concept” achieve true distinction. Finally, there are scholars, such as Abraham Zaleznik (2008), who believe that foxes are good for normal times and hedgehogs are needed in times of crisis, while emphasizing that when hedgehogs are wrong, they are very wrong and can cause a great deal of damage.

Kerr saw himself as one of the last academic hedgehogs but thought that modern universities were facing such complex conditions that they needed foxes to lead them. This book’s thesis is that conditions at present are such that they require hedgehogs at the helm again. This is a time of crisis, which calls for vision more than for shrewdness. It is important to clarify, however, that both hedgehogs and foxes are necessary, and universities should have a combination of both in their leadership teams. Hedgehogs bring a sense of history needed to craft new visions connecting the past with the future, while foxes provide an understanding of geography, of present conditions in the terrain they inhabit, which is necessary to obtain resources and avoid trouble. This book’s premise is not that hedgehogs are good and foxes are bad. Both types of leaders have strengths and weaknesses and can be good or bad. Hedgehogs who create helpful visions are good, while those who come up with harmful ones are bad. Foxes who place their shrewdness at the service of a productive vision are good, while those who use it to advance a pernicious one, or who do not follow any vision at all, are bad. Foxes do their best work when they have a good vision or “hedgehog concept” to guide them, but fox qualities do not lend themselves to the articulation of visions. That is the task of hedgehogs. Some moments in history require a preponderance of foxes, while others call for hedgehogs to take the lead. I think that the current crisis falls into the latter category. What I find worrisome at the moment is the almost total elimination of hedgehogs from leadership teams, which are now almost exclusively populated by foxes. I also am very concerned about the spread of “fox culture,” a free-for-all system, in which foxes pursue goals at random: shrewdness for the sake of shrewdness rather than in the service of a vision. At present, this culture permeates the entire country, which is experiencing what I call “fox fatigue” (González, 2007: 35).

This became evident during the 2008 presidential election, which, in my opinion, showed that the country was calling for the return of the hedgehogs. Interestingly, some journalists used the fox/hedgehog metaphor to describe the various candidates. But there was some confusion about who fit which description and which type of leader was needed more. Thomas P.M. Barnett (2007), who saw George W. Bush as a hedgehog and was unhappy with his performance, concluded that the country needed a fox. For Barnett, the nation needed another leader like Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whom he saw as a fox. Other analysts, however, seemed to favor a hedgehog, even though they thought Bush fit into this category. For example, Arianna Huffington, who in 2004 defined Bush as a hedgehog and Kerry as a fox, stated in 2008 that what the country needed was a hedgehog. If, as Tetlock (2005) indicates, when hedgehogs are right they are very right, and when they are wrong they are very wrong, perhaps Bush was just a hedgehog who was very wrong, and the public was looking for another hedgehog who would set things right. In any case, they clearly favored the hedgehogs (Obama and McCain) over the foxes (Romney and Clinton), and they gave the presidency to the candidate who most resembled Roosevelt.

Why were people so tired of foxes and why was that feeling of exhaustion linked to Bush, who, with his “big” idea of democratizing the Middle East by invading Iraq, seemed to fit the profile of a hedgehog? I think that, whatever Bush was personally, he presided over the declining phase of a fox culture that had developed over the previous few decades. The irony is that this culture, whose internal contradictions brought it to a breaking point during Bush’s tenure, had started to unfold under Ronald Reagan, a confirmed hedgehog, who had enchanted many people with the simple notion that the country could be great again if only it returned to traditional values like self-reliance, which he argued could best be achieved by reducing taxes and regulations, as well as government benefits and services.

Reagan’s vision was a reversal of the one embodied in Roosevelt’s New Deal, which was based on a hedgehog concept of fairness. Reagan’s vision of self-reliance by its very nature fostered, as well as reflected, a fox culture characterized by a lack of solidarity. Individuals were left to their own devices, with the economic elite having very few restrictions on their ability to accumulate wealth and working people having very limited protections from exploitation, leading to their losing ground dramatically. This culture, aided and abetted by members of both political parties, eventually resulted in the current crisis, as deregulatory zeal led, first, to enormous stock and real estate bubbles and then to an equally large financial collapse.

Obama inherited a crisis parallel to the one that Roosevelt faced, and he appears to be attempting to address it in a similar way: by enunciating a new hedgehog concept of fairness to remedy the excesses of the recent past. Obama resembles Roosevelt in many ways, including their combining transformational and transactional characteristics that are the hallmark of successful leaders. Indeed, both demonstrate an interesting combination of fox and hedgehog traits. Roosevelt became president in the midst of the Great Depression. As now, the United States faced a crisis of confidence, and there was a feeling of despair. Roosevelt brought hope to the American people with his New Deal policies, which facilitated a recovery from the crisis. His leadership during World War II helped the country enter its period of greatest splendor. According to Michael R. Beschloss (1981), Roosevelt was a fox who understood the power of ideas, “a leader in search of a cause” who “could horsetrade with the best of transactional leaders” but for whom the presidency “was a platform for transforming leadership” (272-273). Perhaps this is why he surrounded himself with intelligent counselors, including his wife Eleanor, a quintessential hedgehog, whose influence on his political career cannot be overestimated. She was a key member of what has been called his “brain trust” of advisors. I believe that Roosevelt’s love for ideas of all kinds was a hedgehog feature. He may have looked for ideas with randomness, but he articulated them with hedgehog logic in the service of a public purpose.

James MacGregor Burns (1956) uses a different animal metaphor to describe Roosevelt’s leadership style. Instead of the fox and the hedgehog, he refers to the fox and the lion, highlighting the contrast between shrewdness and courage. This metaphor comes from Niccolò Machiavelli (1995 [1513]), who said that rulers had to be both foxes and lions, since the lion “is defenceless against traps” and the fox “is defenceless against wolves” (55). For Burns, Roosevelt was a fox who became a lion when there was a crisis, thus his skilled performance during the Depression and the war. Burns (2003) also describes Roosevelt in terms of being a “transactional” leader who became a “transforming” one, “just as Lincoln had midway through the Civil War” (23). The fox-lion metaphor fails to address the issue of vision, however, which is why I prefer the fox-hedgehog analogy. I believe that Roosevelt’s political trajectory shows a man who was a fox in tactics and a hedgehog in strategy. His biggest accomplishment, and the main reason he is considered a great leader today, was the New Deal, the hedgehog concept of fairness that he articulated and implemented in order to lift the country out of the economic hole into which it had fallen. This achievement made him one of the most memorable hedgehogs in American history.

Like Roosevelt, Obama has been perceived both as a fox and a hedgehog. For example, Huffington (2008) presents him as a hedgehog, but Stephen Clark (2009) believes that he is a fox. Like Roosevelt and other successful leaders, he seems to share traits of both, with his fox side informing his tactics and his hedgehog qualities guiding his strategy. What George Lakoff (2009) calls “the Obama code” is a narrative of fairness that pervades his various policy proposals. All of his initiatives have been connected to this central vision or frame, which according to Manuel Castells (2009), is more than “just words,” because words matter, showing the importance of “communication power” (384).

Curiously enough, during his first year in office, Obama seemed to lose some of this “communication power,” failing to keep what Thomas L. Friedman (2009) calls “the poetry of his campaign” and making some people fear that he was not going to follow Roosevelt’s example after all (Mills, 2010). In large part, this may have been due to his desire not to rock the financial boat excessively, which led to anger by considerable segments of the public. People were furious about perceived financial giveaways to the banking and automobile industries and mistrusted fox maneuvers by members of Obama’s financial team. I believe that the public was angry because, at least with respect to the economy, they did not see a break with fox culture. On the contrary, it appeared that the same players were running the show. The health care debate also contributed to the perception that Obama was losing his focus, as much fox-like maneuvering was employed to pass the legislation, and opposition to it was furious. In the end, however, the health care bill passed and was “the most sweeping piece of federal legislation since Medicare was passed in 1965” (Leonhardt, 2010), firmly establishing Obama’s credentials as a hedgehog.

Albert Einstein (Oakley & Krug, 1991) is credited with having stated that “the significant problems we face today cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them” (13). If the United States is to overcome the fox culture of the last few decades and articulate a new hedgehog concept in this period of transition, more hedgehogs will have to be appointed to top political positions so that they can develop a new level of thinking. The same thing can be said about American universities, which would be well-advised to start looking for administrative teams including critical numbers of hedgehogs charged with crafting a new vision for a country at the crossroads of history. In the knowledge-based global economy, this new vision must include a dramatic increase in access to quality higher education for every segment of the population. The nation needs a master plan for higher education, and it needs optimistic and altruistic Clark Kerrs to make this happen. But where will the Kerrs of the future come from? What will they look like? Just as Roosevelt’s heir apparent does not look like Roosevelt, the Kerrs of the future might not resemble Kerr either. Thus, American universities must cast their nets widely when they look for visionary leaders who can bring about real reform, because now, as always, academia’s role is to serve society, and society is desperately calling for the return of the hedgehogs.

2

Leadership Styles

Kerr’s memoirs provide a great deal of information about his leadership style. A comparison with Gardner’s memoirs is instructive. Kerr was clearly a hedgehog. Gardner, on the other hand, can easily be described as a fox, although Kerr does not use this term to refer to him. Indeed, Kerr does not give any examples of foxes at all, perhaps because being a fox seems less elegant than being a hedgehog. His description of Gardner’s deeds, however, points to positive fox qualities:

Under President David Gardner (1983-92), a wonderful combination of circumstances literally saved the University from academic decline. The economy of the state improved substantially, creating enhanced state resources. The new governor, George Deukmejian (1983-91), had campaigned for office on a program of support for education. Gardner saw the possibilities of the situation, took the risk of proposing, and then securing, the passage of an almost one-third increase in state funds for the university in a single year. His triumph equalized faculty salaries (they had fallen 18.5 percent below those of comparable institutions, see Table 27) and made possible many other gains. That convergence of circumstances and Gardner’s efforts led to the academic rankings of 1993. (Kerr, 2001b: 414)

Gardner recognized the potential for gain and acted swiftly and decisively, a typical fox maneuver. Gardner discusses this and other similar episodes at length in his memoirs, giving us a fascinating insight into the mind of the fox and providing the perfect counterpart to Kerr’s reflections, which show the thinking of a hedgehog. Although Kerr and Gardner were presidents of the same institution, knew each other quite well, and shared many values, they were strikingly different types of people. Kerr’s focus was primarily intellectual, while Gardner’s was intuitive.

This is not to say, of course, that Kerr did not have feelings or that Gardner lacked ideas. On the contrary, both were complex and sophisticated human beings: Kerr had many fox qualities, and Gardner had considerable hedgehog attributes, which is why they were both so successful. Great leaders combine hedgehog and fox traits, with one of them being dominant. Some, like Kerr, are primarily hedgehogs and, thus, more intellectual in outlook. Others, such as Gardner, are essentially foxes and therefore more apt to seek solutions through human interactions. Expanding on the work of such scholars as Lee Bolman and Terrence Deal (1984), and Robert Birnbaum (1988), which distinguish among four cognitive frames for leaders, namely bureaucratic, collegial, political, and symbolic, Estela M. Bensimon (1989) studied the leadership styles of thirty-two university presidents. She found that some presidents had only one style while others combined two, three, or even four. I believe that Kerr and Gardner combined all four traits, with Kerr stronger on the symbolic (articulation of vision) and bureaucratic (codification of vision) and Gardner more attentive to the collegial (human understanding) and political (human negotiation).

It is important to note that although hedgehogs are visionary, foxes are not blind. On the contrary, they can see everything that happens around them very well. They just see different things. Hedgehogs have tunnel vision, a long-range view connecting the past and the future. Imagination is about memory. Visions are built by projecting the past onto the future. Tunnel vision, by definition, has blind spots, and hedgehogs can miss things that are happening in their immediate surroundings. Foxes, on the other hand, have a short-range, circular, view. They cannot see very far ahead. They also are less aware of what came before. What they have is an exceptional awareness of the terrain they inhabit, together with shrewdness to navigate it safely. If hedgehogs are good at history and prophecy, foxes excel at geography and survival. Accordingly, Kerr was very proud of his ability to make accurate predictions about the future, which he usually connected with the past in meaningful ways, while Gardner prided himself on his ability to read present events. Kerr was a collector of concepts, while Gardner was a collector of people.

Kerr, by his own admission, was more intellectual than sociable. He says that he did not like to play golf. In other words, he was not one of the boys. Sometimes, he was not well-attuned to people’s feelings. For example, he confesses that he failed to understand that student activists in the 1960s were moved by passion instead of being guided by a rational cost-benefit analysis. It was a romantic movement, not one seeking compromise, or, as Alain Touraine (1997) says, it was “more expressive than instrumental” (206), but Kerr did not understand that at the time:

I was too accustomed to rational thought within the academic community and the field of industrial relations: verifying facts, clarifying issues, calculating costs and benefits, trying to apply good sense and consider all aspects and consequences of actions. I was not accustomed to a more irrational world of emotions, of spontaneity, of sole adherence to some political faith. (Kerr, 2003: 2...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Clark Kerr’s University of California

- copy

- Contents

- Prologue

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Reading Clark Kerr

- Part I Exploring Clark Kerr’s Thinking

- Part II History of American Higher Education

- Part III History of the University of California

- Part IV Looking for the Clark Kerrs of the Future

- Conclusion: The Roads Ahead

- Epilogue

- Reference

- Index