![]()

1 Climate, culture and weather

Georgina H. Endfield and Lucy Veale

Introduction

Climate is at once local and global, cultural and scientific, political and popular. As an idea, it represents a “statistical construct, consisting of trends and averages that individuals can observe only indirectly” (Goebbert et al., 2012: 132; see also Spence et al., 2011), while discourses about climate have tended to be dominated by a contemporary global, scientific metanarrative of climate change. In recent years, however, it has been argued that climate can and should be localised, historicised and encultured (Hulme, 2012; Livingstone, 2012); should no longer just be the purview of the sciences (Hulme, 2009); and should be “understood, first and foremost, culturally” (Hulme, 2015: 1). In as much, there have been efforts to galvanise “new social understandings, criticisms and practices” of climate (Offen, 2014: 478).

Recent work, for example, has highlighted how the relationships between climate and culture appear everywhere in daily life, in clothing, the built environment, in social memories of past events, in emotions, adaptation, fiction, and in narratives of blame (Hulme, 2015: 1). There is now considerable interest in how different groups of people have conceptualised climate and have responded to its fluctuations (Strauss and Orlove, 2003; Boia, 2005; Behringer, 2010; Dove, 2014; Crate and Nuttall, 2016). A new way of thinking about climate, and so too “about and understanding the hybrid phenomenon of climate change” (Hulme, 2008: 6) has emerged, and there is a growing appreciation that what people make of climate and what they might do about it when it changes, “are complex cultural matters, with a matrix of narratives, specific meanings emerging in and from particular times and places” (Daniels and Endfield, 2009: 222).

To further facilitate a ‘re-culturing’ of climate, it has been suggested that we might “think more directly about weather” (Hulme, 2015: 2). As de Vet (2013: 198) has argued, “in terms of everyday human experience, climate and long term climate change takes expression through specific local weather patterns”. Weather provides the lens through which the relationship between culture and climate is most easily viewed (Hulme, 2008). It can of course also be experienced, monitored, observed, culturally mediated, and has an “immediacy and evanescence” that climate does not (Hulme, 2015: 3). Weather is also very local (Tredinnick, 2013). It sets the background to our lives; it can provide a context, can affect character, and can be used symbolically in stories (Hulme, 2015: 1–2). Yet, there is still a relative lack of research that explores “the interconnections [and] intricacies” of weather’s imprint on societal lifeways (de Vet, 2013: 198). Moreover, with some exceptions (Pillatt, 2012; Hall and Endfield, 2015), only limited attention has been paid to the ‘interconnections’ and ‘imprints’ associated specifically with extreme or unusual weather, such as droughts, floods, storm events and unusually high or low temperatures.

There is particular concern over the impacts of such events, for while social and economic systems have generally evolved to accommodate some deviations from ‘normal’ weather conditions, this is rarely true of extremes. For this reason, these events can have significant and immediate repercussions. Scholarship has tended to focus on the social and economic implications of extreme events (for example Diaz and Murnane, 2008), and more recently, there have been a number of interventions considering the connections between extreme weather and climate change (Hulme, 2014). In this volume, however, we are concerned more with the cultural contingency of such events, on the importance of cultural context in understanding their effects, on the interpretations, articulations and inscription of unusual and extreme weather. We are also interested in the mechanisms through which these events are recorded, recalled, obscured or subsumed by other events. Such histories and memories play a significant role in the popular understanding and articulation of current debates about weather and climate. We bring together scholars whose research on these themes draws on a range of original unpublished archival materials, historical meteorological accounts and registers, newspaper archives, and oral history approaches to investigate cultural histories of extreme weather in a range of contexts and spaces. Through their consideration of distinctive case studies from the UK, Canada, the US, continental Europe and Australia, and based on both land and sea, the authors explore the ways in which different types of unusual and extreme weather have been experienced, perceived and recorded in different contexts throughout history, highlighting how some events become culturally inscribed at the ‘expense’ of others.

The chapters address a number of key framing questions: how and why are particular weather events remembered while others are forgotten? How are weather events recorded and recounted? How have particular weather events become inscribed into the cultural fabric or embedded in environmental knowledge over time? Our authors refer to varied forms of recording and remembering weather and look at how these together act to curate, recycle and transmit knowledge of extreme events across generations. They speak to the different scales and forms of memory-collective, popular, public and counter memory (Glassberg, 1996). They also demonstrate how geographical context, particular physical conditions, an area’s social and economic activities and embedded cultural knowledge, norms, values, practices and infrastructures can affect community experiences of and responses to unusual weather. Adopting Hulme’s terms, all chapters represent a “downscaling” of weather, taking account of location and contingency of place in understanding the physical and mental imprint of weather events (Hulme, 2008: 8).

In order to introduce and situate the chapters, what follows is a brief overview of approaches to and recent work in climate and weather history scholarship, organised by themes that have helped shape the current research and to which these chapters make a significant contribution.

Finding weather: elemental life, ubiquity and the recording of extremes

The weather is ubiquitous. It has been woven into human experience and the cultural memory and fabric of communities through oral histories, proverbs, folklore, narrative and everyday conversation (Strauss and Orlove, 2003). Weather shapes, changes and defines us, and “we are who we are, indirectly and directly, because of the weather we lead our lives in” (Tredinnick, 2013: 15). For this reason, ‘registers’ of weather and climate, as Hulme (2008: 7) suggests, can be read “in memory, behaviour, text, and identity as much as they can be measured through meteorology”. Such non-numerical forms of testimony represent vital media through which information about short-lived weather events, as well as long-term climate change, is gathered and transmitted across generations.

In an 1958 article published in Weather (the journal he helped to establish in 1946 while he was President of the Royal Meteorological Society), British climatologist, Gordon Manley, argued that “in a modern civilisation, the existence of a public memory of the weather is essential” (Manley, 1958: 11). This memory takes many forms. Climate and weather have long been the subjects of private narratives, diaries, chronicles and sermons dating back to the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Jankovič, 2000), and a very diverse group of people were involved in observing and recording weather in this period, either in networks or independently, including gentlemen savants, physicians, sea captains, clergy naturalists, university professors and travellers (Daston, 2008). In the earliest records, emphasis was often placed on “qualitative and narrative framing of ‘important’ weather”, or ‘meteoric’ weather – the unusual or extreme event that disrupted everyday life at the local level (Jankovič, 2000: 9). The “notoriously local and changeable” nature of the weather, however, served to stimulate a motivation to identify some kind of order among the range of “fickle meteorological phenomena” (Daston, 2008: 234–235), and from the mid to late eighteenth century, more quotidian recording practices were adopted, whereby people collated daily weather reports of their local weather, supplemented by readings from meteorological instruments (Golinski, 2003).

Extremes continued to be viewed as noteworthy, however, and many sources contain detailed descriptions of such events and their implications, including from the 1700s local, regional and national newspapers (Grattan and Brayshay, 1995; Gallego et al., 2008). While all our authors draw on a wide range of source materials, including meteorological registers, personal diaries and various forms of narrative account, many of the chapters in this volume make use of newspaper reports, institutional records and bulletins. Ian Waites’ study of the 1976 heatwave and drought in the UK, for example, draws on content from both national and local newspapers, while Cathryn Pearce’s study of shipwrecked fishermen and mariners, and the emergence of benevolent societies in Southwest England, uses materials from local chronicles and weekly gazettes. US-based newspaper reports are central to Cary Mock’s research into historical ‘hurricane memory’, and Alexander Hall makes use of local and regional newspapers in his work exploring the aftermath and commemoration of the 1953 East Coast floods. Newspaper accounts are also central to Ruth Morgan’s study of the cultural memory of the 1914 drought in Western Australia.

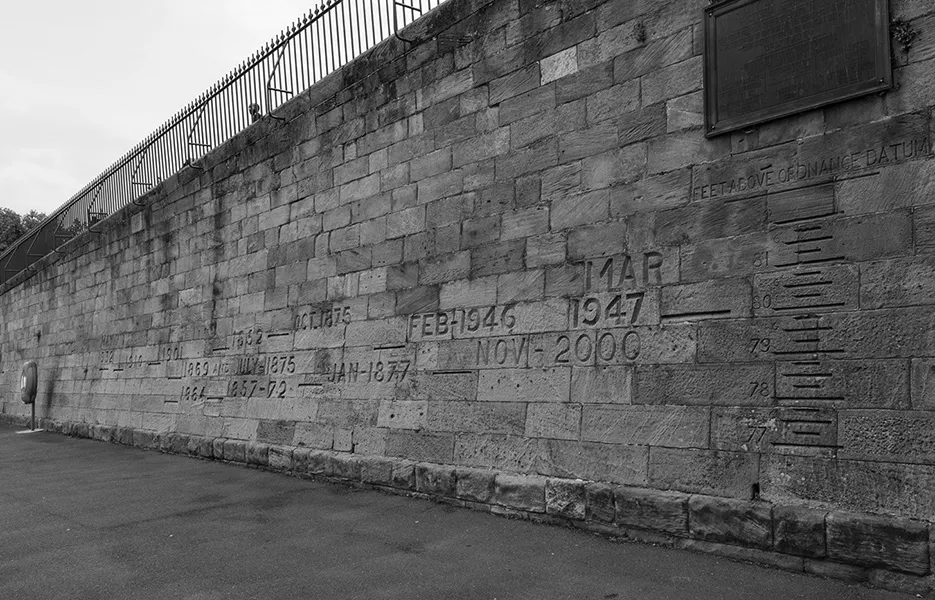

Alongside these direct qualitative and quantitative sources of weather information, there are many other sources of information on historical weather events, including travel accounts, legal documents, crop and tax records, maps, paintings, etchings, plans and images, and collections of correspondence. Many folk traditions express “knowledge regarding the full range of weather and climatic conditions” (Strauss and Orlove, 2003: 7), based on familiarity with long-term climate variability. Extreme weather has also become embedded in the design and construction of vernacular buildings, drainage systems, clothing and alterations to modes of transport (Hassan, 2000). Extreme events that resulted in trauma, such as floods, can result in epigraphic recording of such events, as well as other forms of commemoration. Figure 1.1, for example, shows a set of epigraphic flood markers carved into the wall at the side of the River Trent, near Trent Bridge, in Nottingham, England, demonstrating the way in which particular flood events are remembered and compared. Alexander Hall highlights how similar flood markers at the entrance to St Margaret’s Church in Kings Lynn, the inspiration behind his study, are among the ways in which local weather events can in effect be preserved, as a form of community memory.

The weather is frequently represented or invoked in literature and has been associated with human action and mood in novels, poems and plays. Good, bad or ‘unsettled’ weather provides a backdrop or context for a storyline or is used metaphorically to “intensify the reader’s understanding of emotional states and social conditions” (Collins, 2013: 2). Yet the experience of weather, particularly unusual weather, can also be the subject of purposeful representation. It follows that the impact of weather events on human experience can be traced through literary media. Griffiths and colleagues focus on a medieval poem by Lewys Glyn Cothi to investigate how this form of narrative can provide insight not only into particular flood events in the early modern period but also affords a balanced view of flooding as a part of everyday life in what they term a ‘hydrographic culture’, a society that kept records of their relationship to local hydrology. The poem represents a form of ‘flood heritage’ and is a valuable source for anyone interested in the environmental impacts of extreme flood events, including on trees, and in the historic practice of assigning human characteristics to rivers and their behaviour.

Tapping into local weather memories through interview and oral history work can yield very useful information on perceived changes in such unusual events, their frequency and intensity, and the impacts and responses they engendered, as well as revealing how people conceptualise and contextualise the risks of any future events (Leyshon and Geoghegan, 2012). Short, retrospective, interview approaches have proved to be useful for establishing how people are able to generate valuable autobiographical experiences of weather and the everyday (de Vet, 2013) as well for as retrieving memories. Moreover, such personalised weather narratives have a significant role to play in popular understanding and articulation of debates about weather and climate (Lejano et al., 2013). Marie-Jeanne Royer adopts this approach in her work to explore intergenerational ecological knowledge and perceptions of a changing climate based on weather memory and wisdom among Cree communities in Canada, while Ruth Morgan highlights the utility of pre-existing oral histories for revealing the deeply personal nature of the drought response in early-twentieth-century Western Australia and the contested cultural memory therein.

Social networking and sharing platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Flickr and YouTube offer opportunities for innovative public geographies (Kitchin, 2013), including historical ones. These kinds of digital approaches not only “open up… new forms of representation… and expanded publics” (Yusoff and Gabrys, 2011: 519) but also represent the repositories of future weather memories. Contemporary instances of unusual or extreme weather are now perhaps more likely to be captured and recorded through webpage entries, blog narratives and tweets as they are in newspaper reports or other written records. These forms of social media, however, can also provide a medium through which to assemble memories of past weather events. Ian Waites’ chapter on the 1976 heatwave, for example, makes extensive use of online reminiscences of the event, demonstrating the rich empirical information on weather memory that is retrievable from blogs and other web entries, and highlights the value of online repositories as examples of future cultural memory.

The waxing and waning of weather memory: remembering (and forgetting) weather events

The chapters in this volume all point to different forms of weather memory but also consider how those weather memories have been made. Hywel Griffiths and colleagues, for example, discuss the ‘encoding’ of weather memory, which is subsequently transmitted across generations through “a complex series of occurrences” – written and performed, collected and curated. Memory tends to be distorted with respect to more recent extreme weather events, according to what Harley (2003) refers to as the “recency effect”. Indeed, as Eden (2008: 4) has suggested, with the exception of the most extreme or unusual events, “once a weather phenomenon has reached two years old it seems to fall out of the human memory bank”. In a UK context, for example, exceptionally severe winters, such as 1947 and 1962–1963, and indeed the summer of 1976, though recognised to be extreme, appear also to have claimed priority in people’s memories as idealised stereotypes of seasonal conditions. Such events are often regularly considered to be ‘unprecedented’, the memory of similar events in the past having effectively been overwritten by a more recent event.

This issue of ‘forgetting’ is raised in Cary Mock’s chapter on US hurricane memory. Memory of these events, he argues, falls into three categories: persistent memory, intermittent memory and lack of memory. Storms associated with persistent memory, and which are defined as those having a significant legacy, are memorialised largely because they affected populous areas, causing loss of life and widespread damage. Those events associated with intermittent memory tend to be those that are forgotten but rediscovered numerous times during anniversaries or in association with education and outreach efforts. Storms associated with a lack of memory, by definition, are challenging to interpret, but likely relate to those events that affected rural or remote areas or perhaps caused little or negligible damage.

Particularly dramatic or extreme events or those that resulted in major disruptions tend to seize popular attention and “evoke strong feelings, making them memorable and, therefore, often dominant in processing” (Marx et al., 2007: 48). There is also a tendency to remember events from the distant past with greater clarity if related to unusual weather. In this respect, weather provides a metacognitive role in organising memory (Harley, 2003), and unusual or extreme weather events can act as “anchors for personal memory...